The 26 Most Important Ideas For 2026

Modern trends and history lessons—across culture, politics, AI, economics, science, and the long story of progress. But first: an announcement!

Thank you all so much for reading and subscribing to this newsletter. It’s been an absolute blast whose success in its first six months has tremendously exceeded my expectations. If you’re arriving for the first time and like what you see, please subscribe.

A little life update: Last week, my wife delivered our second baby girl. I’ll be off for a short bit to fetch bottles and wash bottles and dry bottles and even drink some bottles (wine), but this newsletter won’t stop publishing. I’ve lined up some fantastic essays from great writers on economics, psychology, artificial intelligence, and more. The plan is to continue to publish roughly once-a-week for a little while, before I roll back onto full-time work. I’m excited for you to read these upcoming pieces and even more excited to announce plans to grow this newsletter in 2026.

But first, here are 26 ideas for 2026, organized under the themes that I think will drive economics, politics, and technology in the near future.

‘EVERYTHING IS TELEVISION’

The end of reading

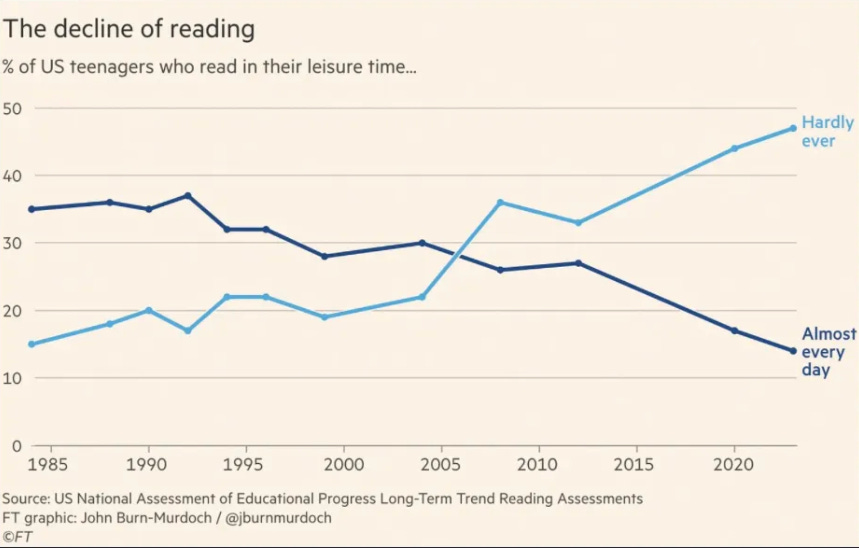

I was born in 1986. By the time I was 10, or so, it was natural for me to come home and read for hours after school. The Lord of the Rings, Asimov’s Foundation series, and other fantasy and science-fiction classics were my favorites. This didn’t seem like a particularly special or noteworthy thing on my part. Throughout the 1990s, the share of teenagers who read daily outnumbered the share who read “hardly ever”, according to long-term reading surveys. But in the last 25 years, this has flipped so dramatically that today roughly half of teens say they hardly ever read for fun. The teen who reads daily is on track to become an endangered species.

I’ve covered this theme consistently in the newsletter, although I admit that writing essays about how nobody reads anymore is sort of comically futile, like writing aria after aria about how nobody listens to operas. In any case, if you’re still reading this, then you should know the broader context for this decline in teenage leisure reading. National reading scores have fallen to a three-decade low for American students, and the share of Americans overall who say they read books for leisure has declined by nearly 50 percent since the 2000s. “Most of our students are functionally illiterate,” a pseudonymous college professor wrote. Last year, The Atlantic’s Rose Horowitch reported that elite college students are arriving on campus without having ever read a full book. Our attention is moving from the printed word to the streamed image, which is naturally leading to:

The triumph of streaming video

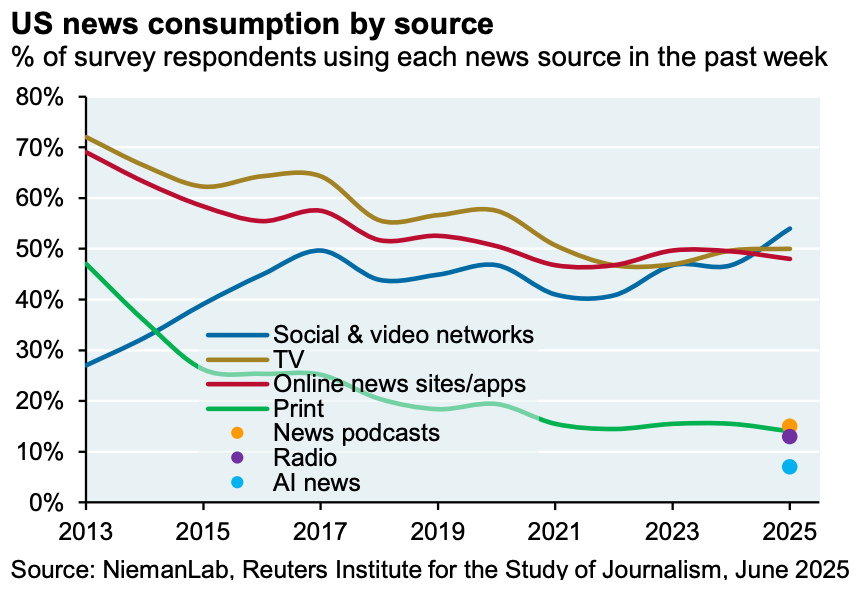

In my essay “Everything Is Television,” I wrote that all media are converging toward the same flow of video. Social media is becoming less about keeping up with friends and more about watching short-form videos made by strangers—i.e., television. Podcasts are becoming less about listening to Internet radio and more about watching YouTube talk shows—i.e., television.

According to JPMorgan, the share of Americans who say they get their news from print has declined by about two-thirds since the early 2010s. Cable television and websites are also declining by this measure. “Social and video networks,” such as TikTok and YouTube, are gobbling up news consumption.

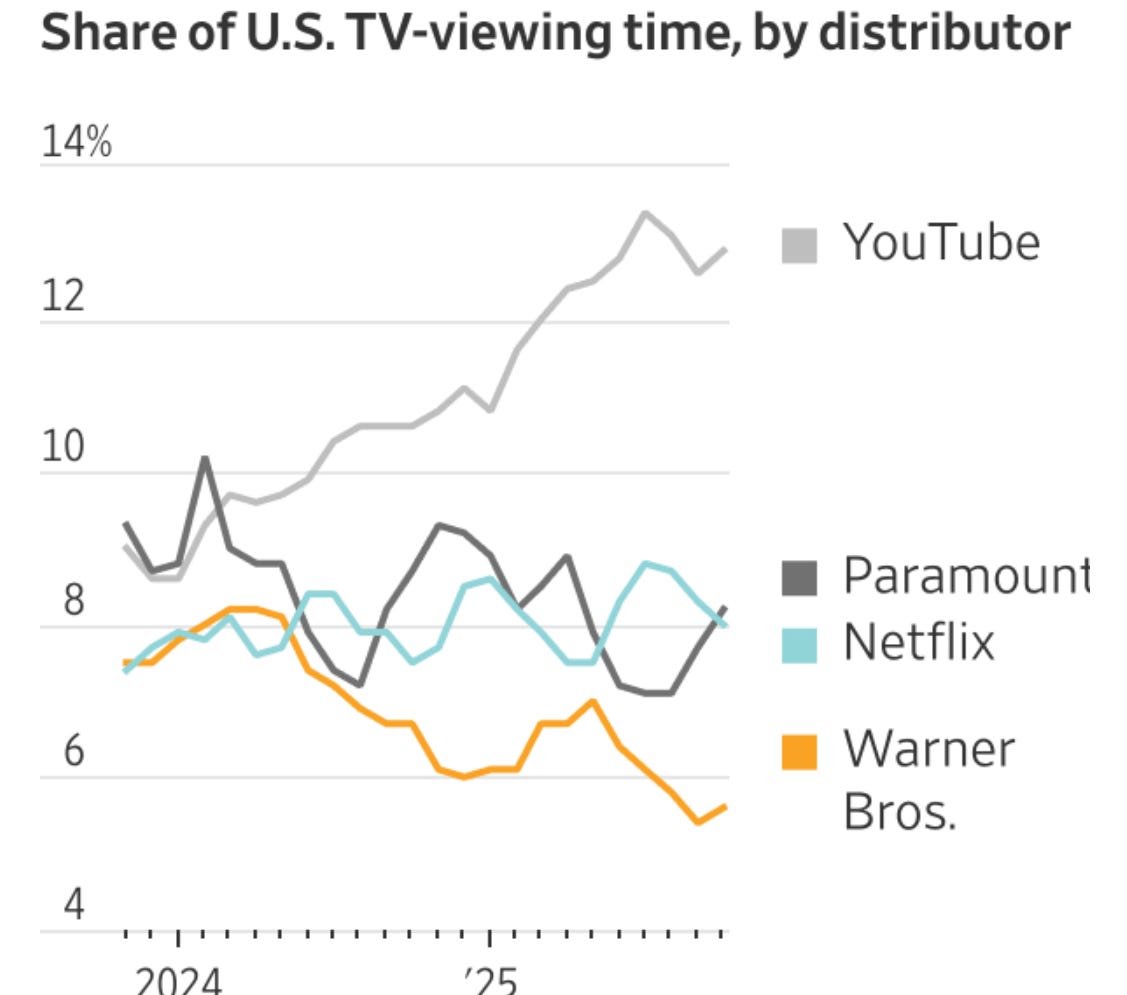

Within that category of “social and video networks,” YouTube’s recent surge might be the most notable. In just the last two years, YouTube has dramatically increased its share of “TV-viewing time,” according to the Wall Street Journal, and it now accounts for about 50 percent more viewing time than Netflix, far surpassing traditional Hollywood firms like Paramount and Warner Bros. Discovery.

Goodbye, movie theaters?

On Friday, Netflix announced its intention to buy Warner Bros Discovery for $83 billion, in a deal that will give the world’s largest paid streaming service access to famous entertainment brands, such as Harry Potter, and power over theater owners and entertainment unions. (On Monday, Paramount announced an even pricier hostile takeover bid.) Either way, the acquisition of Warner Bros. will likely lead to job losses, as industry consolidation continues in the beleaguered movie business.

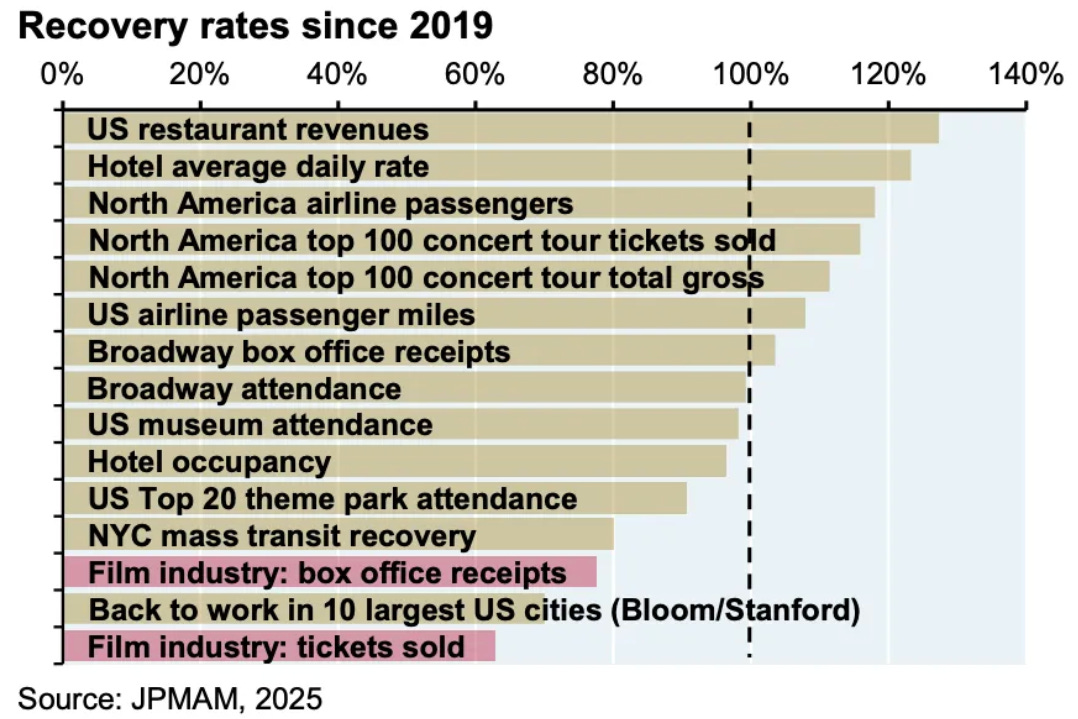

While most industries have recovered from the pandemic—restaurant revenues and hotel rates are running 20 percent higher than their pre-COVID levels—the number of movie tickets sold in 2025 is on track to be about 30 percent lower than in 2019, according to JPMorgan.

It’s not that movie theaters are over, exactly; it’s more that their structural decline will likely accelerate. Americans bought between 1.2 and 1.5 billion movie tickets every year in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. I don’t think Americans will ever buy a billion movie tickets a year again. The entertainment experience is continuing its decades-long evolution from a collective and out-of-home experience (the cineplex, the opera house) to a solitary and at-home experience (phones, AirPods). And what is that doing to us? Well:

TikTok might be melting your brain

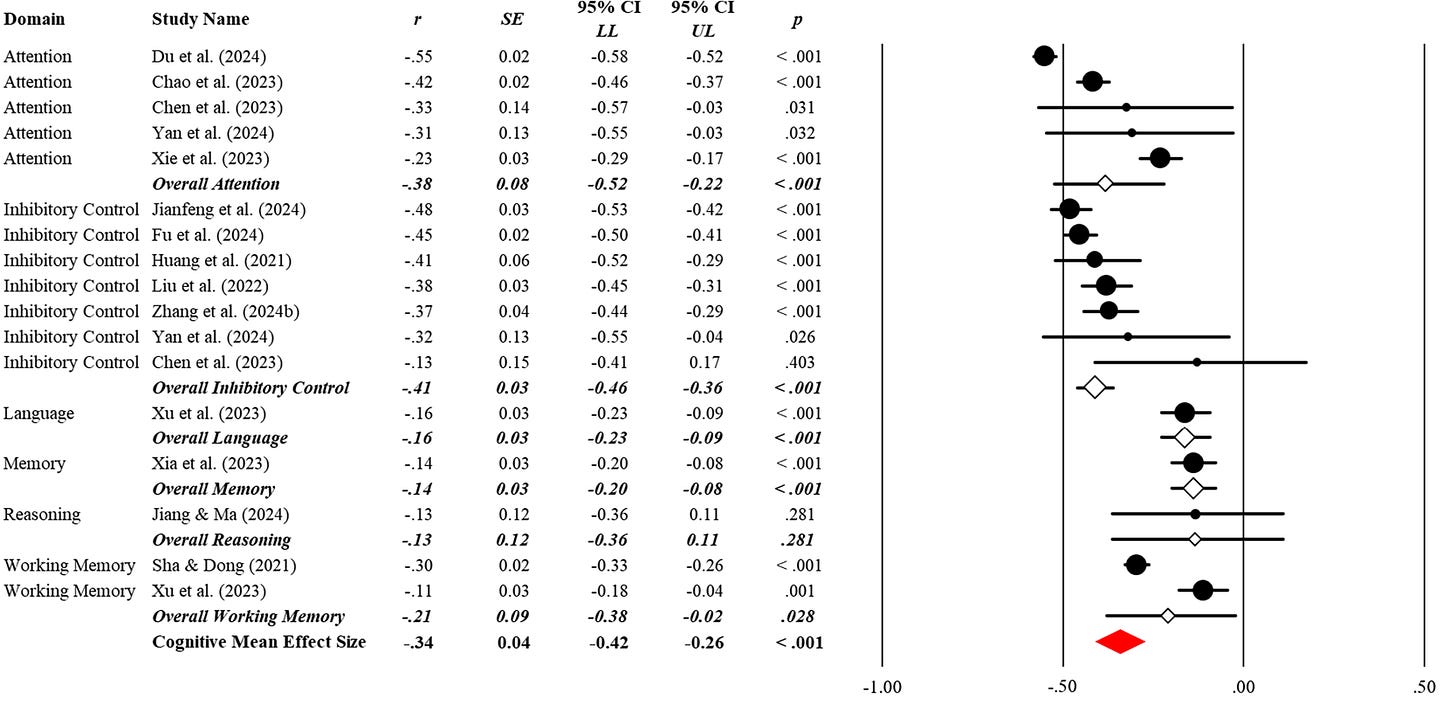

The frustrating truth is that we don’t really know for sure what the digital empire of short-form video is doing to our minds. But a systematic review of 71 studies with 98,000 participants published in 2025 reached an alarming finding. Across the dozens of studies, heavy short-form video users showed moderate deficits in attention, inhibitory control, and memory. In the chart below, you can see a consistently negative, if also heterogeneous, relationship between heavy short-form video use and problems with attention, memory, and control.

Several studies in the meta-analysis reported structural and functional differences in the prefrontal cortex and reward circuits among high-frequency users, while others found cognitive flexibility reductions and altered dopaminergic reward responses. None of this proves causation. But taken together, they suggest a plausible mechanism: a daily diet of hyper-rewarding, rapid-fire stimuli may gradually reshape attention and regulatory systems in ways that weaken our attentional control. It is, of course, possibly that people with weaker cognitive control are simply more drawn to slot-machine media in the first place.

To separate cause from effect, the field needs longitudinal and experimental work. Until then, I’d prefer to live by the words of organizational psychologist Adam Grant: “Long live longform.”

AI IS EATING THE ECONOMY. IT WILL SOON DOMINATE POLITICS, TOO.

The whole US economy right now is one big bet on artificial intelligence

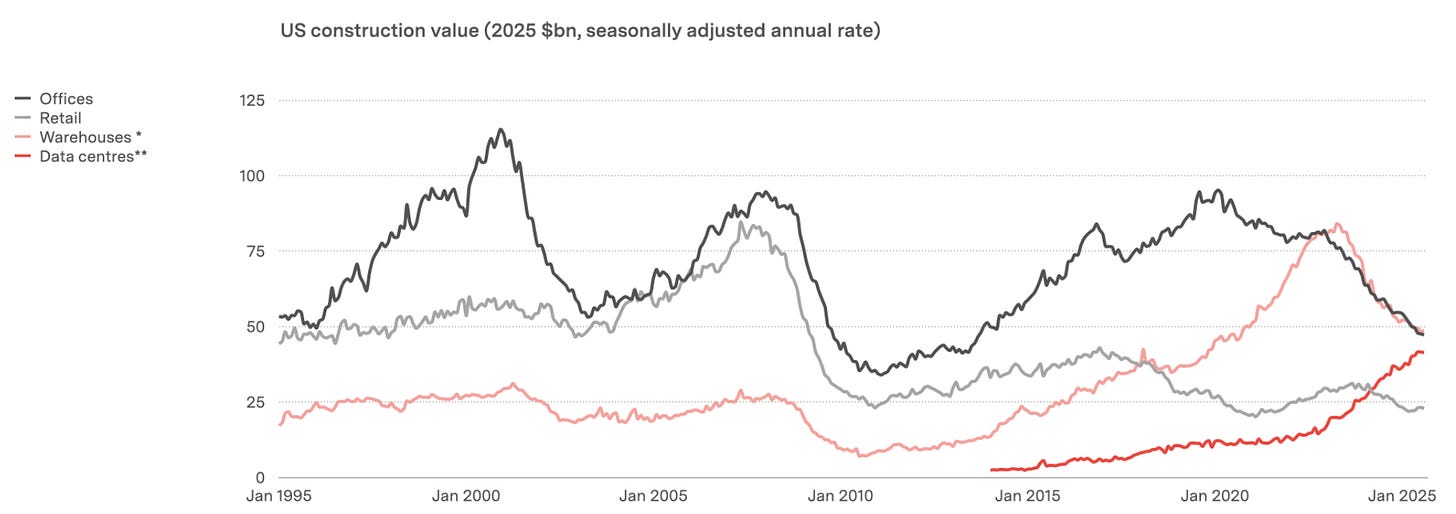

Housing is in a rut. Farmers are hurting. Manufacturing has been shrinking for months. Hiring is hell. And yet, the US economy continues to grow, powered by an AI infrastructure project unlike anything in modern history.

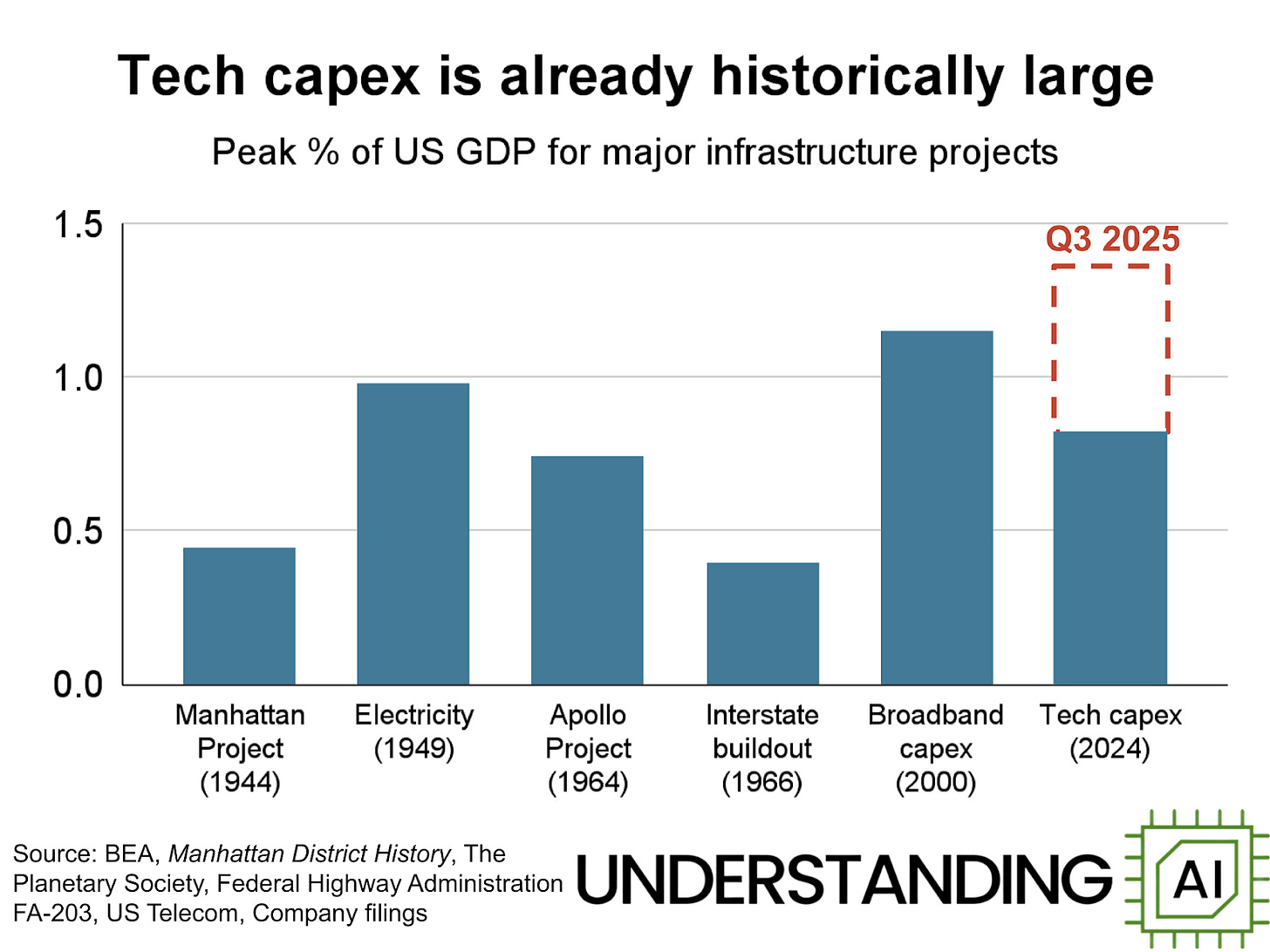

I have written so much about AI in the last few weeks, but I want to emphasize this particular statistic to hammer home the sheer audacity of the construction project. In the last three months, the hyperscalers — Meta, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Oracle — spent more than $100 billion on AI infrastructure, including chips and data centers. That is the inflation-adjusted equivalent of three Manhattan Projects … in three months! At this rate, the AI build-out will outspend the entire Apollo program, every year, despite being financed by the private sector.

Get ready for a wave of anti-AI populism

Affordability is the watchword of 2020s politics. As the AI buildout continues to pull electricity and manpower from other parts of the economy—and as it creates a new class of AI billionaires and near-trillionaires—it seems inevitable to me that the future of populist politics is going to revolve around attacking AI and its architects, for better or worse.

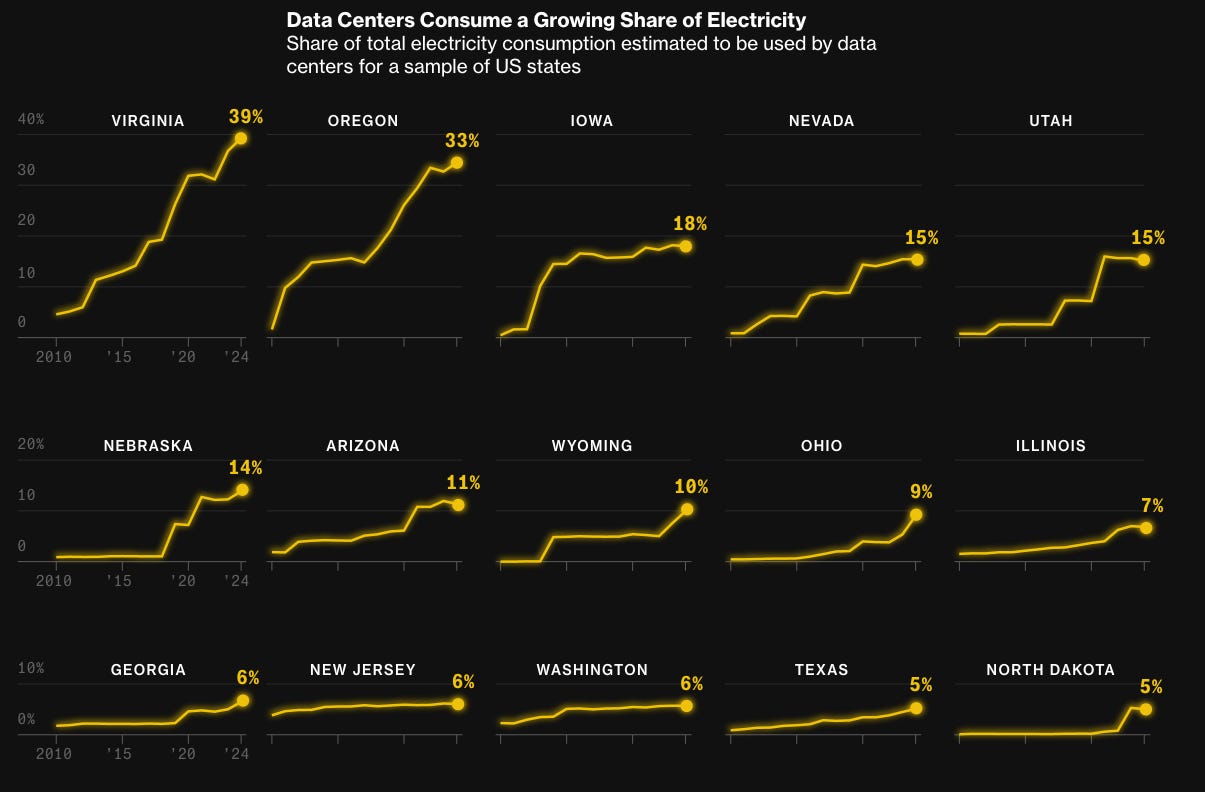

As Bloomberg has reported, wholesale electricity is “up to 267 percent more expensive than it was five years ago” in areas near US data hubs. In Virginia and Oregon, data centers reportedly consume one-third of the state’s electricity.

Data center construction isn’t likely to slow down. In the last two years, it surpassed the value of all national retail. At some point in 2026, data center construction could outstrip that of offices and warehouses. Love it or hate it, we are concentrating an enormous share of the economy on this AI bet, and you’re going to hear more from politicians who see an opportunity to funnel voter anger through a clear anti-AI populism.

Generative AI is probably much better at (certain aspects of) our jobs than we’d like to admit

I find that the online, podcast, and cable-news debate about artificial intelligence often conflates three very different questions. (1) Is AI an industrial or financial bubble? (2) Is the AI buildout “good” for the typical American worker, in the short run? (3) Is generative AI effective and useful?

Some commentators who represent themselves as pro-AI will say yes to all the above. They’ll argue that AI is not a bubble; that it’s good for workers; and that it’s very useful to today’s employees. AI critics are likely to align themselves on the opposite side of each issue: AI is bubbly, bad, and bogus.

I don’t know the answers to questions (1) and (2), yet. But I know the answer to question (3): AI critics are kidding themselves when they insist that artificial intelligence is a mere trillion-dollar auto-complete machine with limited utility in the workforce.

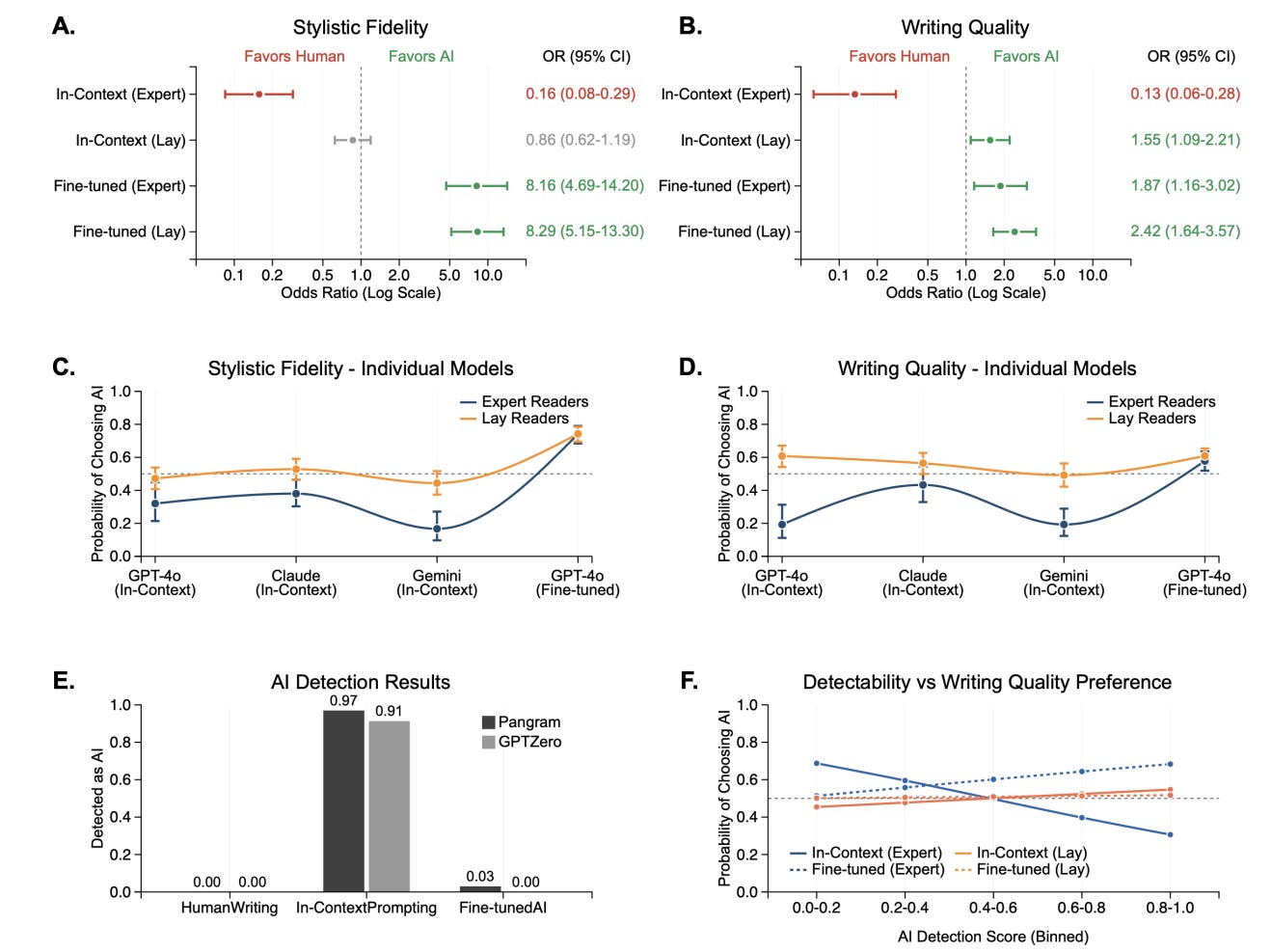

For example, it’s become common for writers to mock AI’s stilted, wooden, and em-dash-heavy writing style. But with some gentle coaxing, AI is much better at writing than professional writers want to admit. In one 2025 study by researchers at Stony Brook, Columbia University, and the University of Michigan, three top AI models were pitted against MFA-trained writers. In initial tests, expert readers clearly preferred the human writing. That’s comforting. But once researchers fine-tuned ChatGPT on an individual author’s full body of work, the results flipped. Suddenly, experts preferred the AI’s writing and often couldn’t tell whether it came from a human or a machine.

The emphasis on slop in AI commentary sometimes operates as a coping mechanism, which allows AI’s critics in creative industries to console themselves with fairy tales about AI being permanently sub-human at every creative task. The future will be filled with slop. But it will also be filled with stories, images, videos, and writing that will seem indelibly human, even when its silicon-based author lives in a data center in Virginia.

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH GEN Z?

Young Americans are becoming more disconnected from the economy.

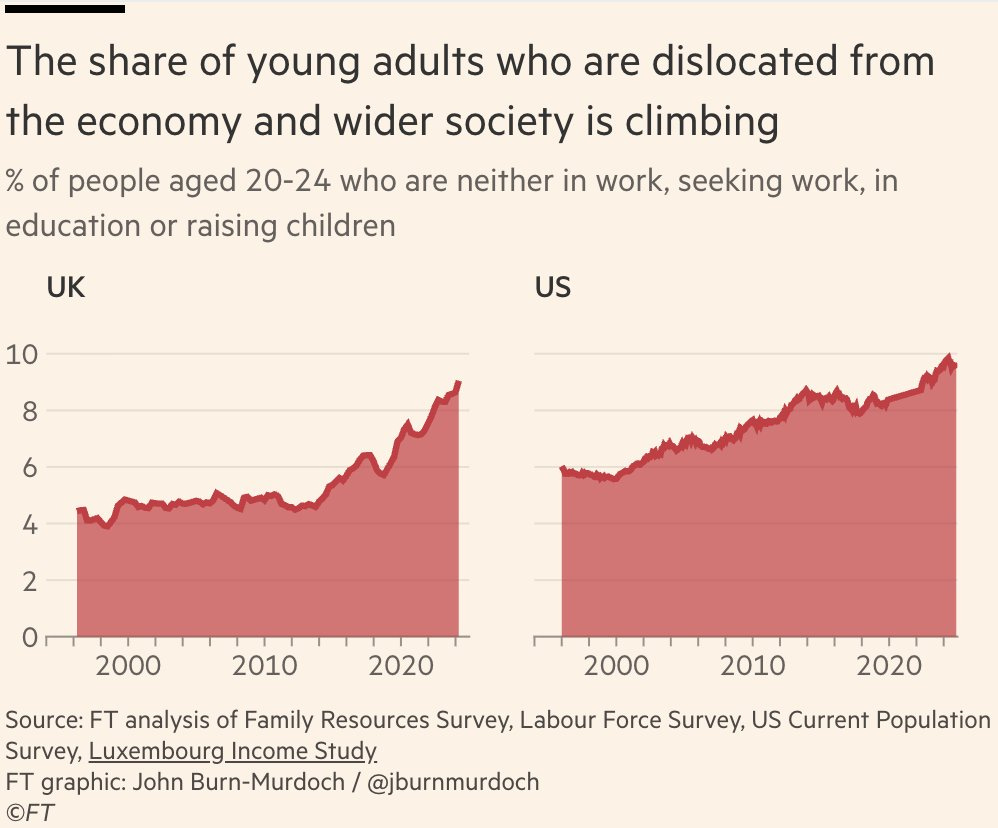

In my November essay “The Monks in the Casino,” I wrote that many young people, especially men, spend a historically unusual amount of time alone while gambling online on sports, meme coins, and other fluctuating assets. The Financial Times’ incredible James Burn-Murdoch found an ingenious way to render my essay in statistical format, by graphing the rise in young adults who have been dislocated from the economy in the last 25 years. His main finding: The share of people between 20 and 24 who are not in a job, or seeking work, or in school, or raising a child has nearly doubled in the last quarter-century in both the UK and the U.S.

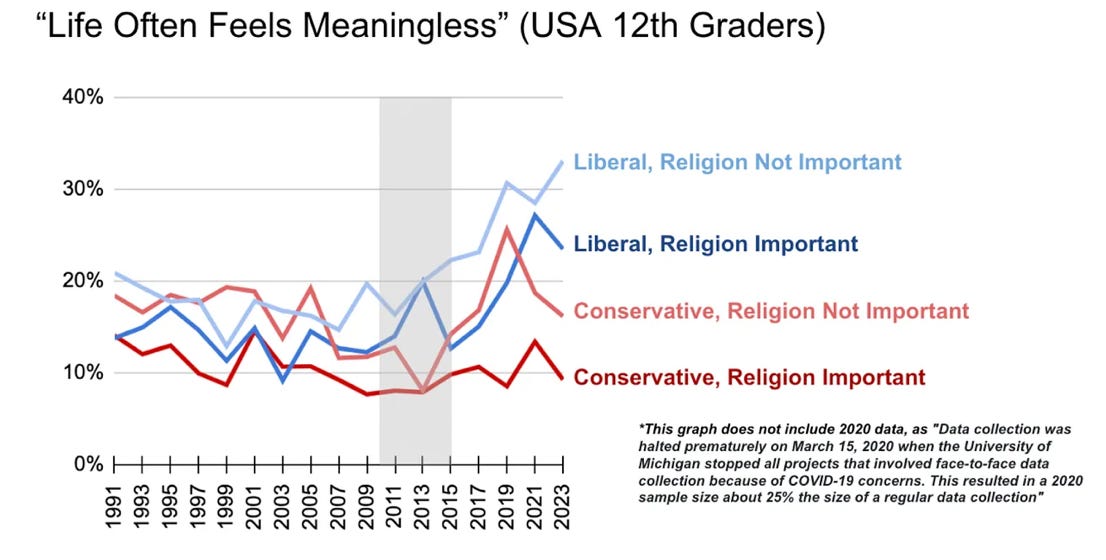

The share of liberal non-religious high school seniors who say life “often feels meaningless” has doubled since the early 2000s

Yes yes yes, it’s old news at this point: Teen anxiety and depression have increased in the last 15 years. What’s less widely appreciated is that the increase is most dramatic among the most secular and liberal teens.

Religion and conservatism seem to offer protection against the generation-wide increase in negative affect, as Jon Haidt has written. Self-described conservatives and teens who said “religion is important in my family” suffered smaller increases in depression and anxiety. Haidt suggests that conservatism and religion might offer a binding moral matrix that protects young people from a rapidly changing world, while progressive moralities aim to grant people more freedom to “create their own identities.” There is an idea that comes from the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard that, whereas pre-modern people were lost in finitude—that is, their choices were constrained by tradition or religion or economy—modern anxiety comes from an opposite affliction. We are lost in infinitude, the boundlessness of choices. “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom,” Kierkegaard wrote. Perhaps despair is a natural side effect of some liberal ideologies, even as those ideologies are necessary to free us from the constrains of tradition.

The only currency is currency (Or: Have you noticed that the only remaining global virtue in the world is money?)

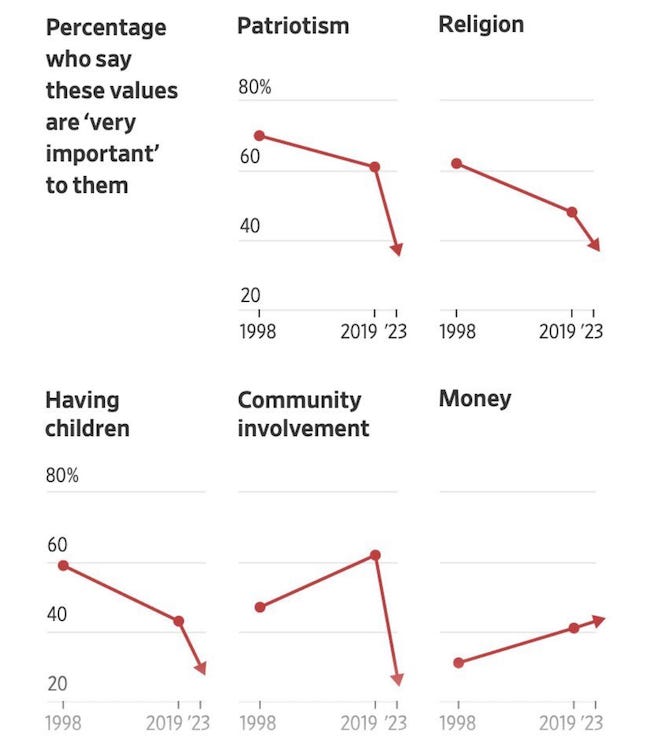

Americans, and particularly young Americans, don’t really care about patriotism, or marriage, or family, the way they once did. A 2023 Wall Street Journal poll found that a shrinking share of Americans agreed that practically any of these virtues were “very important.” There was one exception: money.

Americans are pulling back from “values that once defined them,” the WSJ said. Nature, abhorring a vacuum, is filling the moral void with the market. You see across several studies that young people care much less than their parents or grandparents about getting married or having children. What they do say they care about is finding a job and getting rich. I am not prepared to judge this shift in values. Jobs are important, and money is nice to have. But I think there’s much more to be said about the idea that every non-market value is plummeting in relevance among young people.

In his book After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre argued that the modern world had lost the sort of shared moral language that was once provided by virtue systems, such as religion. I think that’s half-right. We have lost something with the erosion of religion, perhaps, but we’re still bound by an ethical system, love it or hate it. It’s the market. What binds the modern world is our collective reverence for money.

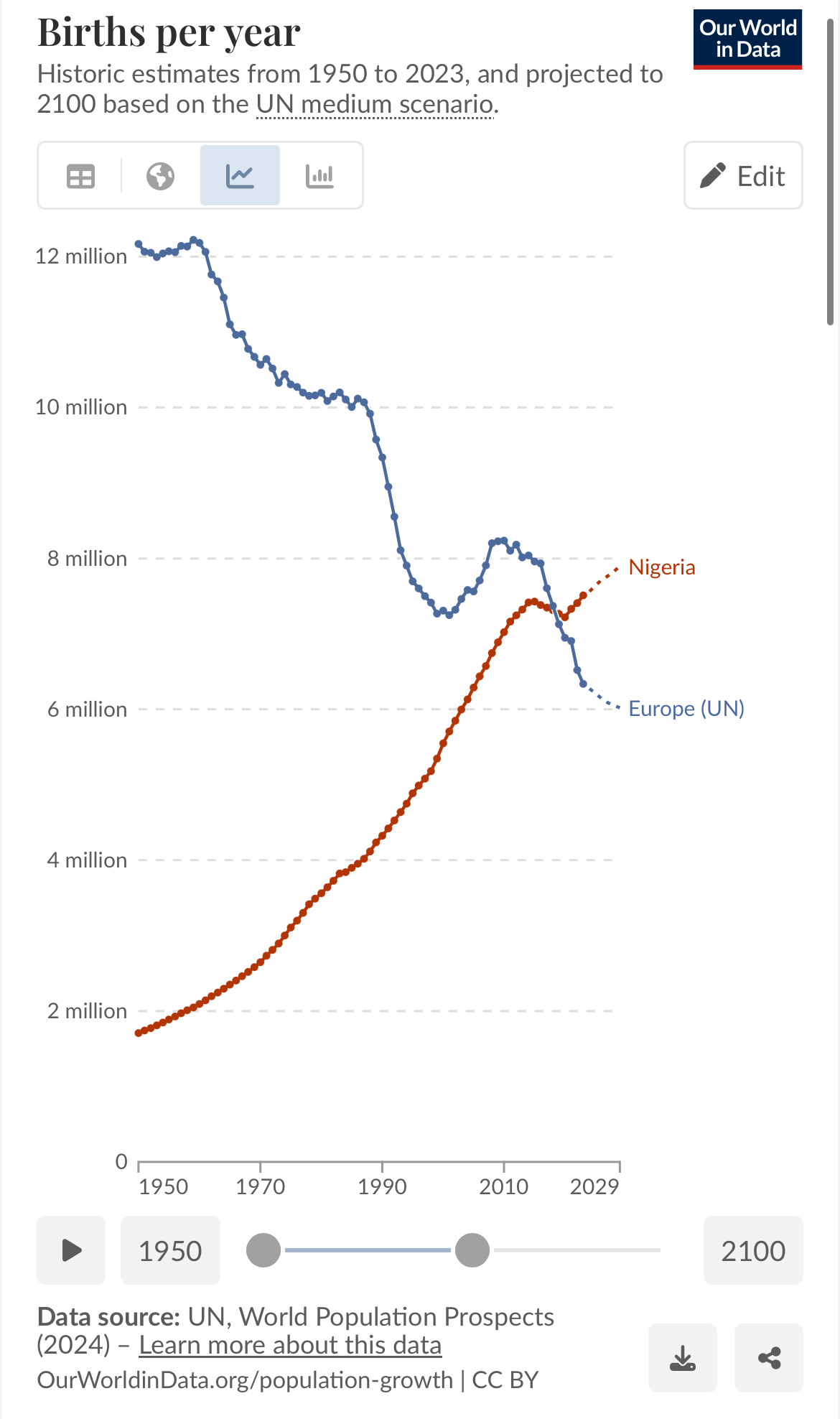

The accelerated decline of fertility among rich countries is going to have some fascinating global implications.

Presented without comment:

AMERICA IS ON DRUGS

Is alcohol over?

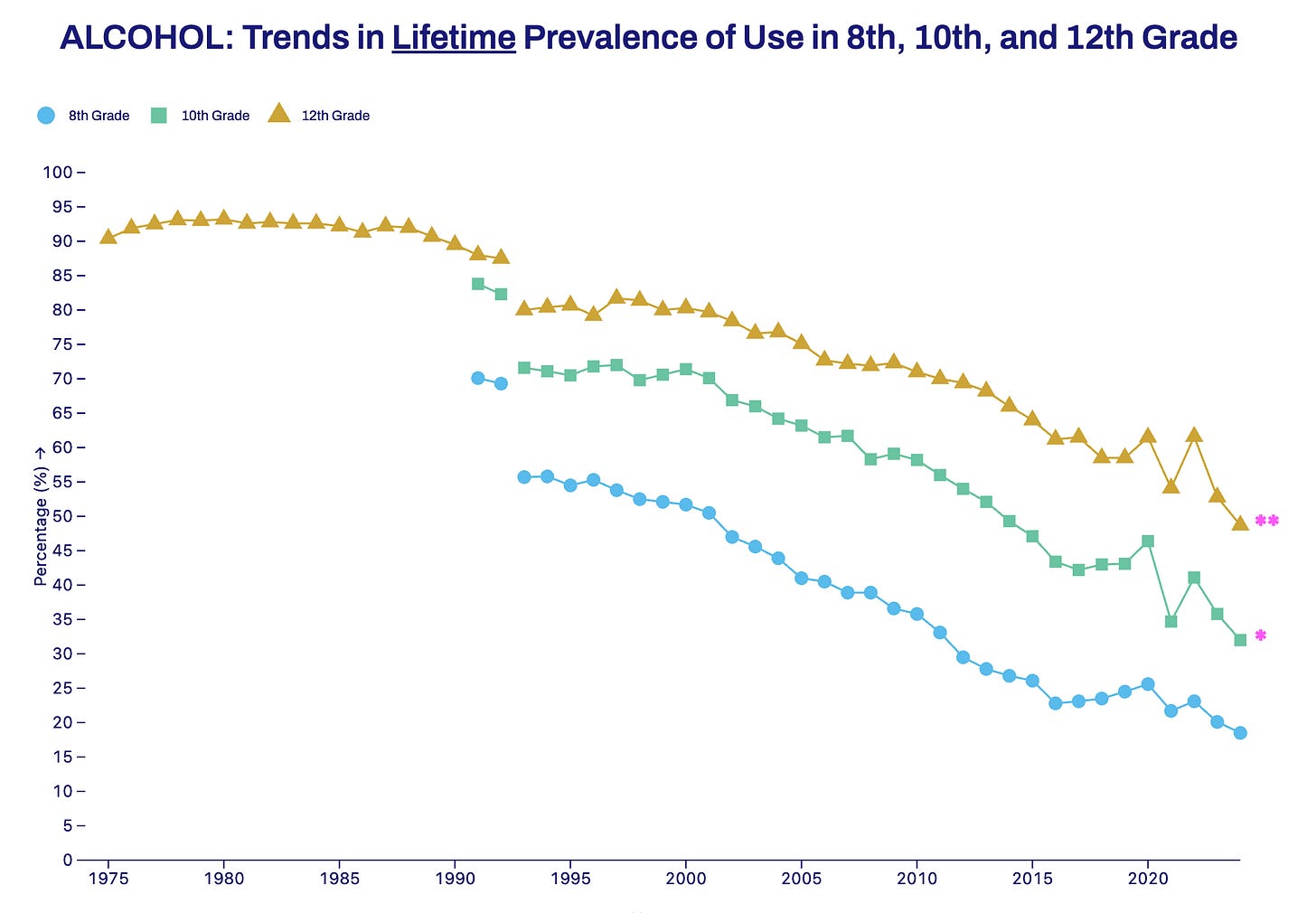

The share of Americans who say they drink alcohol hit a record low in 2025. Despite the US population growing by tens of millions since 2000, total beer consumption just hit a 21st-century low. Wine vineyards are “in crisis.” And Gen Z is leading the way:

Last year was the first time on record, going back to 1975, that fewer than 50 percent of high school seniors said they’ve ever had a drink of alcohol. The sharpest declines in drinking have been among younger teens. As I’ve said before: Today’s 12th graders are now less likely to have had a sip of alcohol in the previous month than the 8th graders of the 1980s. That’s crazy!

But at the same time that alcohol consumption has declined, something else has surged to take its place.

Americans aren’t drunk. They’re high.

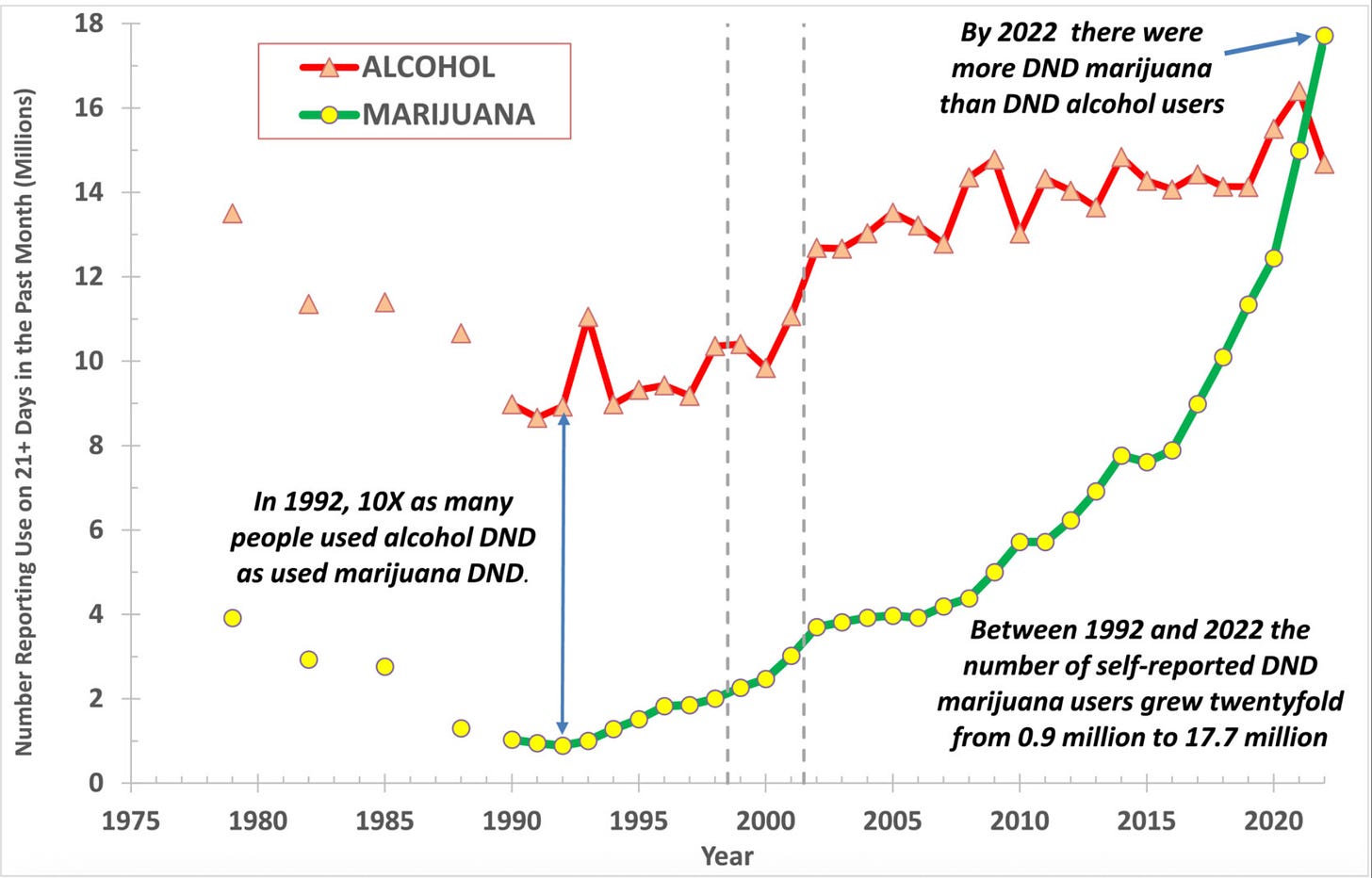

In 2010, daily or near-daily drinkers outnumbered daily marijuana users by a two-to-one margin. But since then, a wave of decriminalization has allowed marijuana use to soar into the 2020s, so that today daily marijuana users exceed drinkers for the first time ever.

Some of these daily or near daily users are using using marijuana once in a while to chill out and relax and disconnect from their busy brains. That’s fine. It might even be good. Suicide rates among older Americans seem to decline slightly following the opening of nearby recreational marijuana dispensaries, especially for older white men with less education. But just because a little weed can be narrowly helpful for some people doesn’t mean a lot of weed is broadly helpful for many people using it as a cure-all for chronic pain, sleep, and depression. The explosion of cannabis usage would be great news if research showed that marijuana reliably solved the problems it’s used to solve. But … does it?

Marijuana isn’t good medicine.

It’s easy to get the impression that cannabis—and its non-psychoactive cousin, CBD—is the new aspirin. It is everywhere, promising to fix everything. More than a quarter of adults in North America say they’ve used cannabis medically, and more than 1 in 10 Americans are currently using CBD to treat some kind of ailment. But our enthusiasm for medical marijuana is running way ahead of the scientific evidence.

A 2025 review of studies on the medical use of marijuana found that, although cannabis-based drugs help with nausea and appetite loss for very sick patients, their other medical uses “aren’t supported by good evidence.” Instead, frequent marijuana users report higher rates of “psychosis, anxiety, addiction, and heart and stroke problems.” Most concerning, more than one-third of people using medical cannabis meet criteria for cannabis use disorder.

No, marijuana probably isn’t good medicine. But another chemical with skyrocketing usage seems to be a very good medicine.

GLP-1 drugs are already remarkable, and today they’re probably less effective than they’ll ever be.

Studies show that GLP-1 drugs don’t just help patients with type-2 diabetes and promote weight loss. They seem to provide a range of benefits affecting just about every biological system. By targeting abdominal fat, they seem to protect against heart disease, even in patients who don’t lose weight. Mice treated with GLP1s experienced body-wide anti-aging effects, even on minimal dosage. In the latter study, researchers ran the mouse version of a full-body diagnostic workup: gene expression, proteins, metabolites, inflammation markers, functional strength tests, and more. Across almost all those systems, the older mice on GLP-1 drugs shifted in the direction of youth. Not a little shift. A big, across-the-board, multi-omic reversal of aging signatures. And since this happened with a small amount of GLP-1 that didn’t really change the animals’ weight, it hints that the effect isn’t about calorie restriction or dieting. It’s something else happening inside the body.

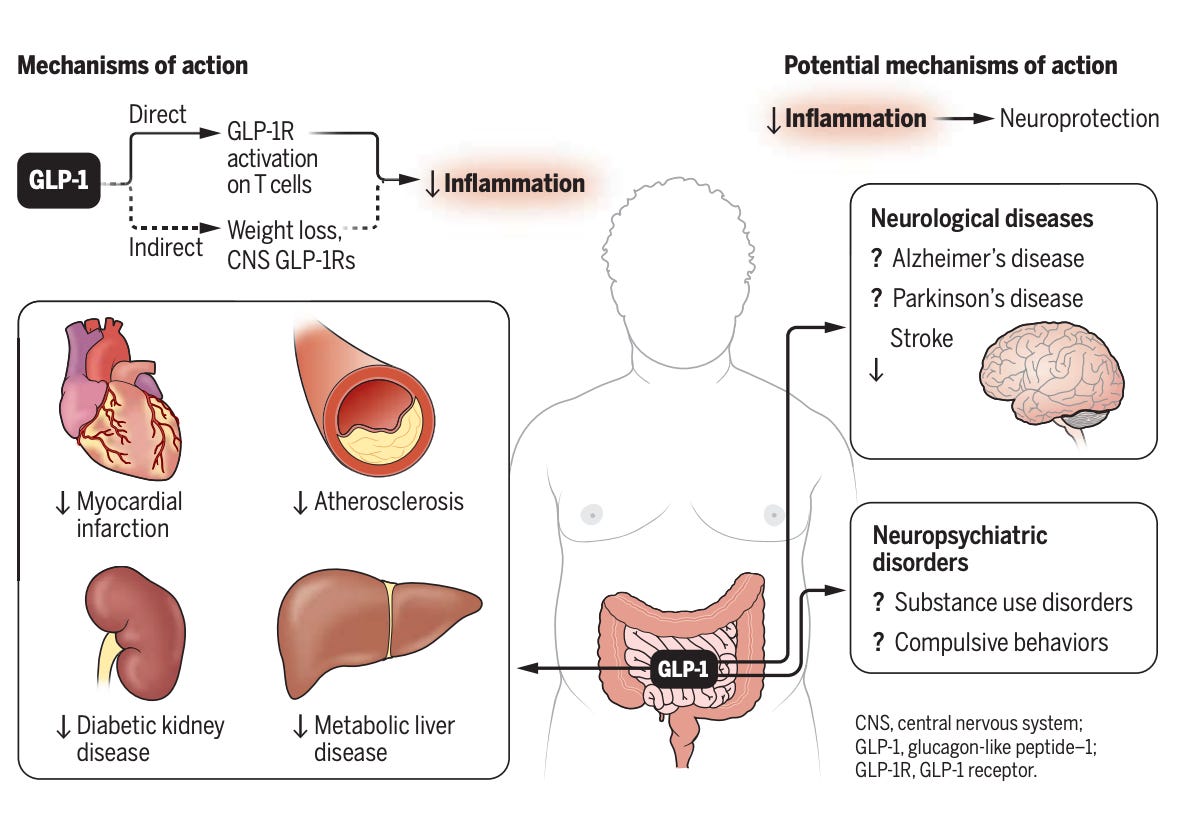

How is this possible? The Canadian scientist Daniel Drucker, who has done more than practically anyone in the world to illuminate the benefits of GLP-1 drugs, proposed that GLP-1’s anti-inflammatory effects could provide a “unifying” mechanism for these drugs’ effectiveness:

When our bodies notice germs or tissue damage, our immune response brings immune cells to the area. (Think about how your knee feels warm when you bang it; that’s normal inflammation.) But excessive chronic inflammation, which results from an immune system over-policing threats throughout the body, is a leading cause of organ damage, stroke, and neurological problems. GLP-1 drugs seem to bind to receptors throughout the body—in our gut, on our immune cells, and throughout the central nervous system—to broadcast the same message: STOP THE ATTACK! LESS INFLAMMATION, PLEASE! Drucker provides this illustration of the mechanism:

Panaceas don’t exist, and GLP-1s can’t do literally everything. I suspect that in the next 12 months we’ll hear about both their remarkable side effects and their limitations. For example, Novo Nordisk recently concluded a randomized double-blind trial of semaglutide for Alzheimer’s patients. The company found that the drug doesn’t slow progression of that disease. Well, drat. But the future is long, and I’m still on the lookout for GLP-1 spinoffs that provide more benefits with fewer side effects than the current models.

GLP-1 drugs will probably reshape the food and drink industry.

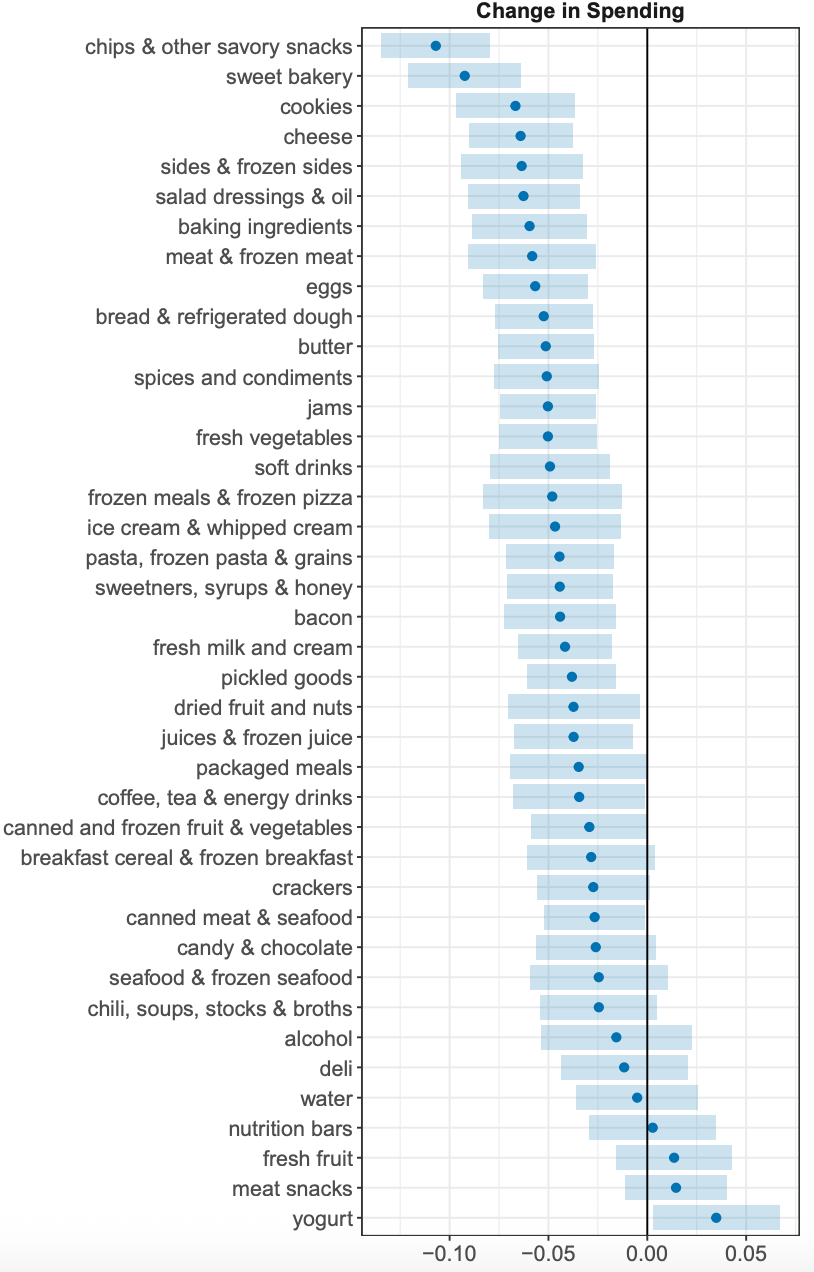

A 2025 study from Cornell University found that households with at least one GLP-1 user reduced their overall grocery spending by about 5 percent within six months. Richer families cut their grocery bill by even more. While most food categories saw spending declines, the largest reductions were concentrated in salty snacks and sweet desserts. Chips and “other savory snacks” got walloped, with a 10 percent decline. The big winner? Parfaits, apparently. Spending on fresh fruit and yogurt rose in GLP-1 households.

The future will be hot, high, and lonely.

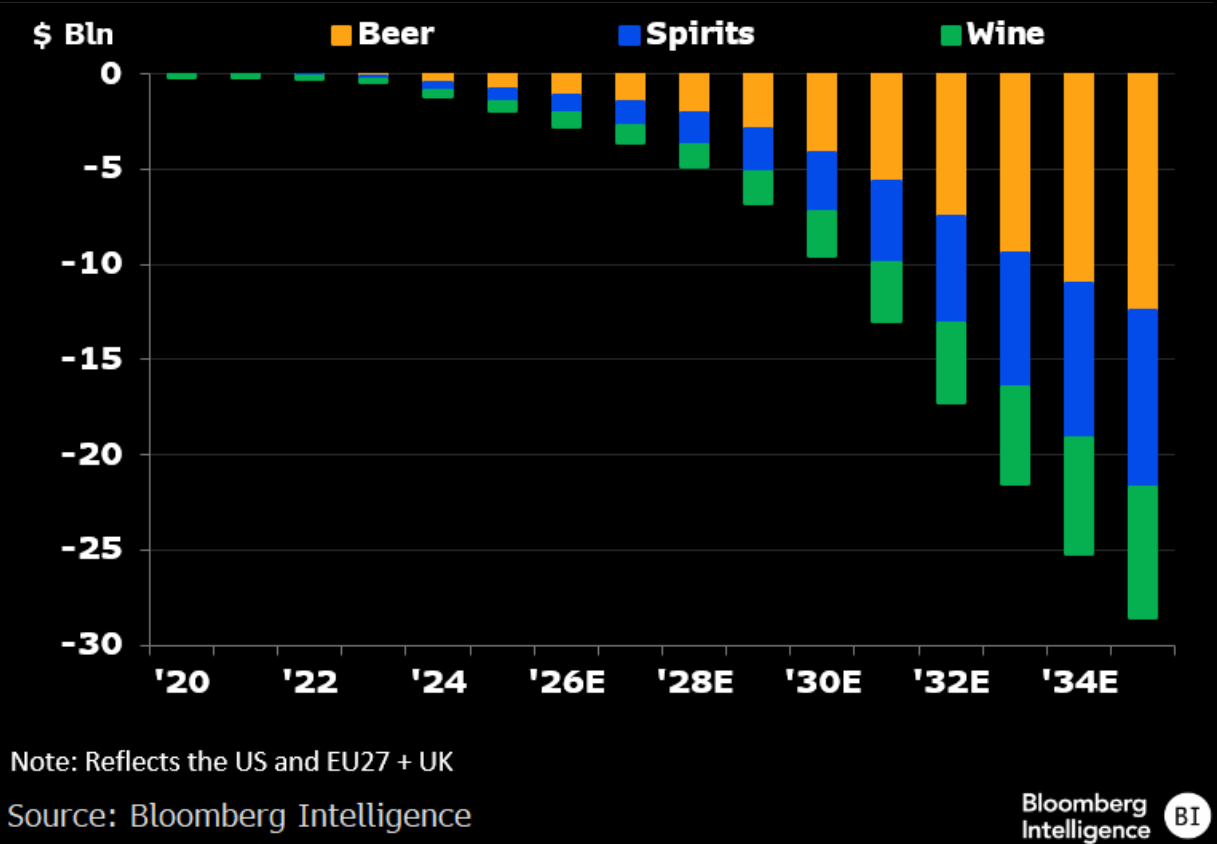

The alcohol industry is terrified about the effect that GLP-1 drugs could have on their business. And maybe they’re right to be. According to an analysis shared with me by Bloomberg Intelligence, total spending on beer, wine, and spirits in the U.S. and Europe is projected to decline by nearly $30 billion in the next decade. Spending on sweet and salty foods are also projected to decline by $25 billion in that period.

That’s how these threads all come together: The rise of marijuana is coinciding with a weight-loss drug revolution that will significantly reduce spending on alcohol, which is coinciding with state-by-state changes that are making it easier for people to get access to cheap weed. The age of alcohol is over, and the future looks ominously like hundreds of millions of people getting high alone rather than getting tipsy together. In the last two decades, Americans under 25 have reduced the time they spend partying by 69 percent, which is not nice. Humanity will be extremely attractive, with better weight-loss drugs, better face lifts, better plastic surgery ... and fewer friends and parties. The future will be hot, high, and lonely.

And one more thing about drugs: The right’s vaccine politics are insane.

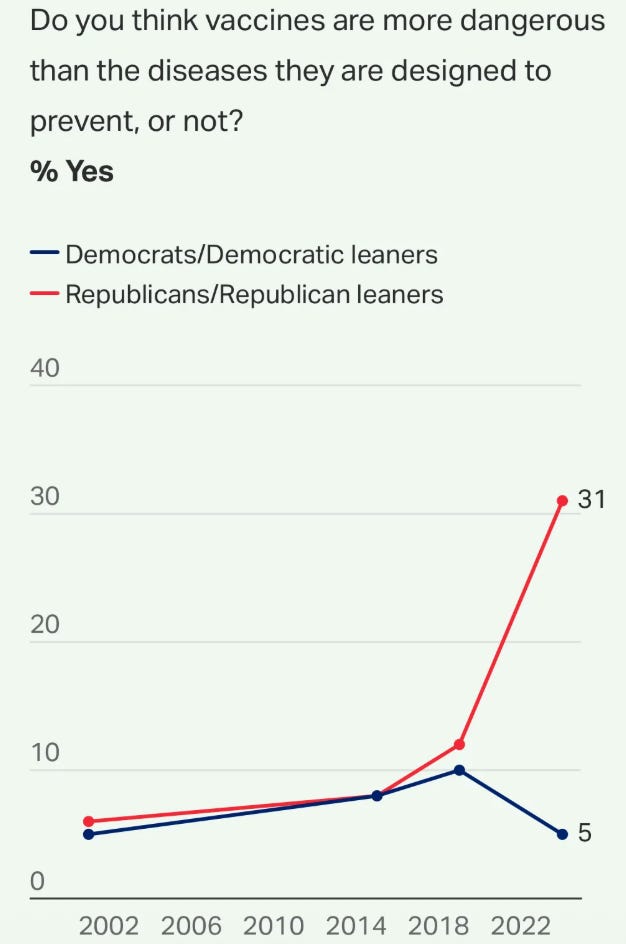

Several hundred years ago, one-third of all babies died before their first birthday. Half of all children died before the age of 10. Infectious disease kill about a quarter of the survivors by the time they turned 50. Smallpox, measles, and diphtheria killed more efficiently and voluminously than any military force ever assembled. Blessedly, we have devised vaccines to protect against smallpox, measles, mumps, tetanus, diphtheria, and other horrors. And yet the leading party in the U.S.—the party responsible for the most successful national vaccine policy in human history!—has responded to this miracle by advancing anti-scientific conspiracy theories that have frightened a third of their coalition into believing that vaccines are little more than a state-mandated poison.

Dostoevsky once wrote that you could give a man every earthly blessing— “drown him in a sea of happiness, so that nothing but bubbles of bliss can be seen on the surface”—and require of him nothing but to “sleep and eat cakes.” Even then, the Russian said, something in the dark basement of human nature would rise up inside of us to destroy utopia out of sheer ingratitude. “He would even risk his cakes,” Dostoevsky wrote, “and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive good sense his fatal fantastic element.” The anti-vaccine turn on the American Right is many things. It is the culmination of anti-tech naturalism, anti-government skepticism, and look-at-me-I’m-so-clever contrarianism. But it is also the very same brain rot diagnosed more than a century ago by Dostoevsky. It is a sickly inclination to identify a fatalistic element in all things, even those which are overwhelmingly good for us.

THE CASINO ECONOMY AND THE WAGES OF DESPERATION

Young people are screwed because of housing. So … what’s the matter with housing?

It has become conventional wisdom in certain corners of the commentariat that today’s young people are screwed and that the vibecession so brilliantly coined by Kyla Scanlon reflects a material reality, which is that today’s youth have been dealt a particularly awful hand. I did my best to evaluate the accuracy of the “Young People: Screwed” narrative here, but for today’s purposes I want to focus on the challenges in the housing sector.

It’s best to see the problems with the US housing industry as three stories: a 50-year story, a 20-year story, and a 5-year story. The 50-year story is that anti-growth rules have accumulated in America’s most desired metros, making it harder for supply to meet demand in the places where demand is highest. The 20-year story is that the Great Recession decimated the construction industry, which made the 2010s a uniquely awful decade for nationwide housing additions. The 5-year story is that the pandemic created a berserk housing market that set new weird records every year.

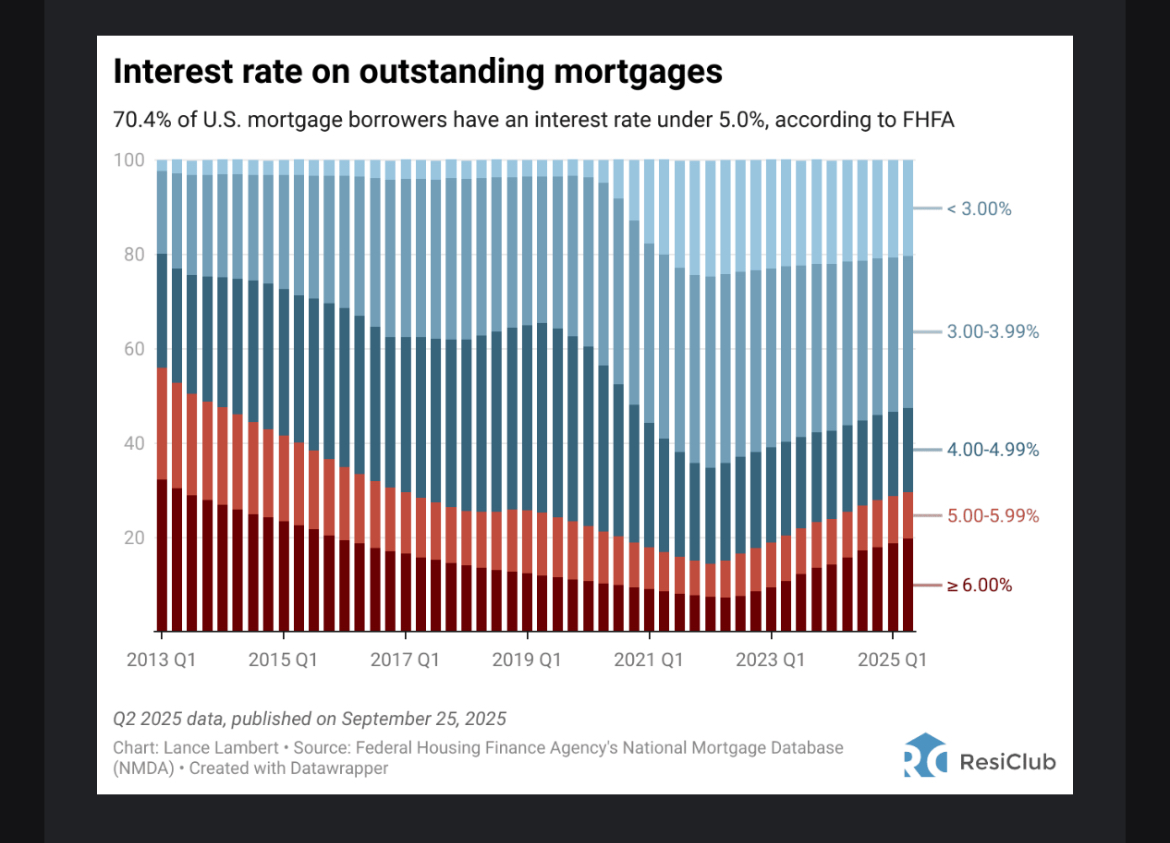

The latest weird housing record, as Bloomberg’s Conor Sen points out, is that new home prices are now lower than resale prices—”a historical rarity,” he says, which hasn’t happened in at least 50 years. Existing owners really, really, really don’t want to leave their houses. One reason: Many would-be sellers have low mortgage rates they don’t want to give up. I think this graph is the best way to drive home the point. The 30-year fixed rate mortgage is over 6%. But half of homeowners are paying off mortgages with interest rates under 4%. (Incredibly, there seem to be roughly as many homeowners paying mortgage rates over 6% as there are homeowners paying under 3%.). So, in many markets—especially in the northeast and midwest—the reason you can’t find a home to buy is that owners aren’t selling, and they’re not selling because of this graph.

Blocked from homeownership, low-income renters are gambling with their housing money

On a podcast with Conor earlier this year, he suggested to me that the stock market boom might be an unintended consequence of the shitty housing market. Initially, I thought it was a crazy idea. How could a bad housing market be good for stocks and other assets?

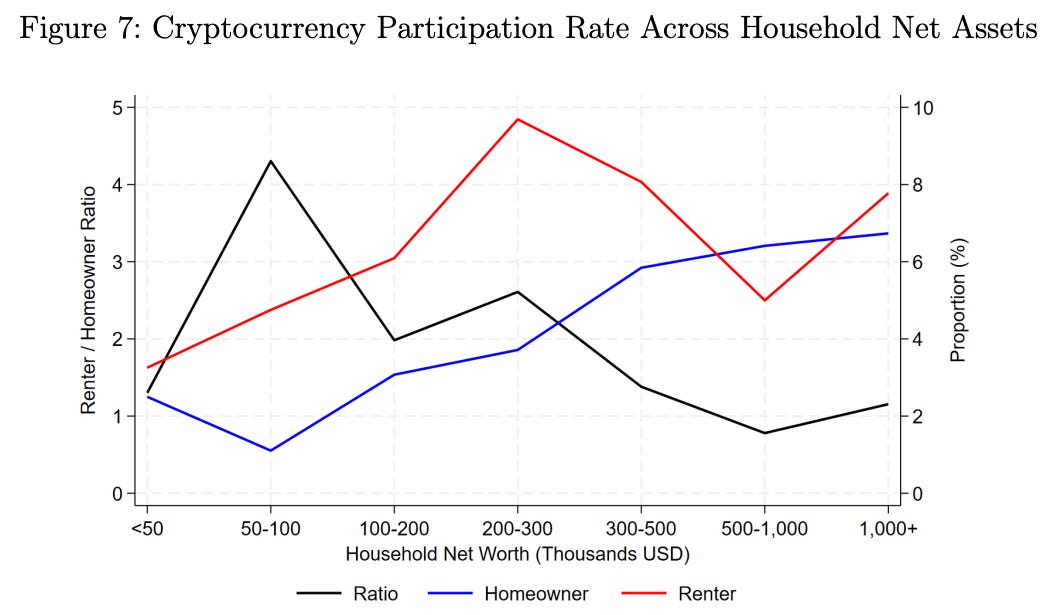

The logic went something like this: Many young people, blocked from ownership, are funneling their spare cash toward meme stocks, meme coins, and gambling. In fact, a 2025 paper by researchers at Northwestern and the University of Chicago found that crypto investing is most common among middle- and lower-middle-class renters. On its own, this fact is sort of bizarre: For most asset classes, investments rise with income. But these renters, who are on the verge of homeownership, seem to be “gambling for redemption”—that is, taking bigger risks on speculative bets to get that final windfall that will make homeownership possible. In essence, these economists discovered a large group of younger Americans who are treating the US economy like a slot machine that they hope will return a pile of coins that they can turn into a house.

America’s “monks in the casino” are calling for help

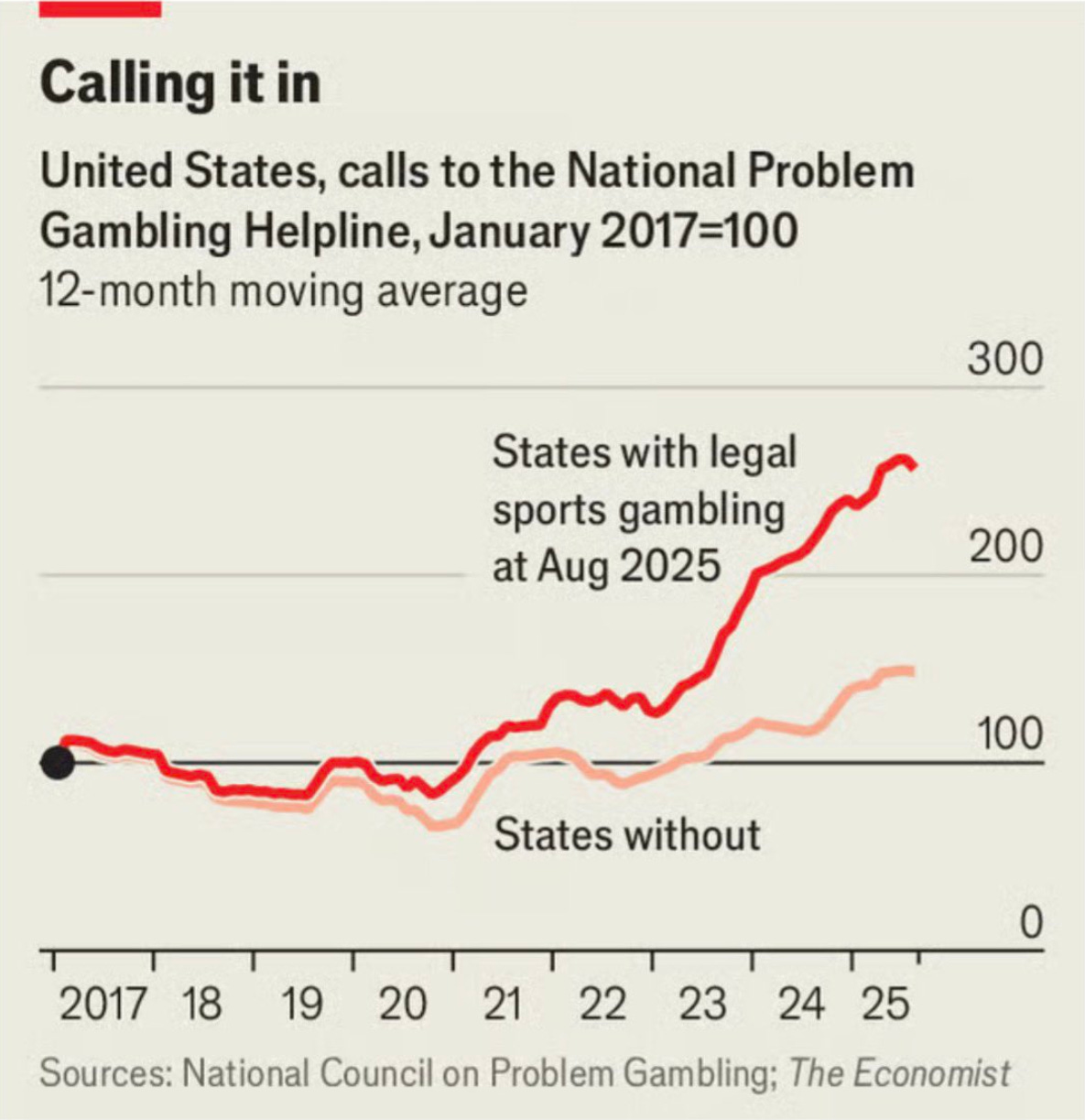

The Substack essay that I’m most proud of is “The Monks in the Casino,” a theory of young men, aloneness, and the market. As I wrote in that piece, roughly half of men between the ages of 18-49 have a sports betting account. In New Jersey, nearly one in five men aged 18-24 is on the spectrum of having a gambling problem, according to the author Jonathan Cohen. And here is The Economist calculating that calls to the National Problem Gambling Helpline have nearly tripled since 2017 in states that have legalized sports gambling.

PROGRESS EXISTS. BUT WHO WANTS TO HEAR ABOUT IT?

Negativity bias rules everything around me

People sometimes talk in a high-minded way about the concept of media literacy, which I think refers to the ability to separate truthful news from disinformation and misinformation and other forms of information with prefixes. That’s all fine, but if I had one hour to teach Americans about the news industry, I think I’d spend most of it talking about the concept of “negativity bias creep.” I’ll define negativity bias creep here as the tendency of ideological media—or news media with a point of view—to recognize over time that audiences prefer negative stories to positive stories and thus, in an attempt to reflect audience preferences, to become more negative over time.

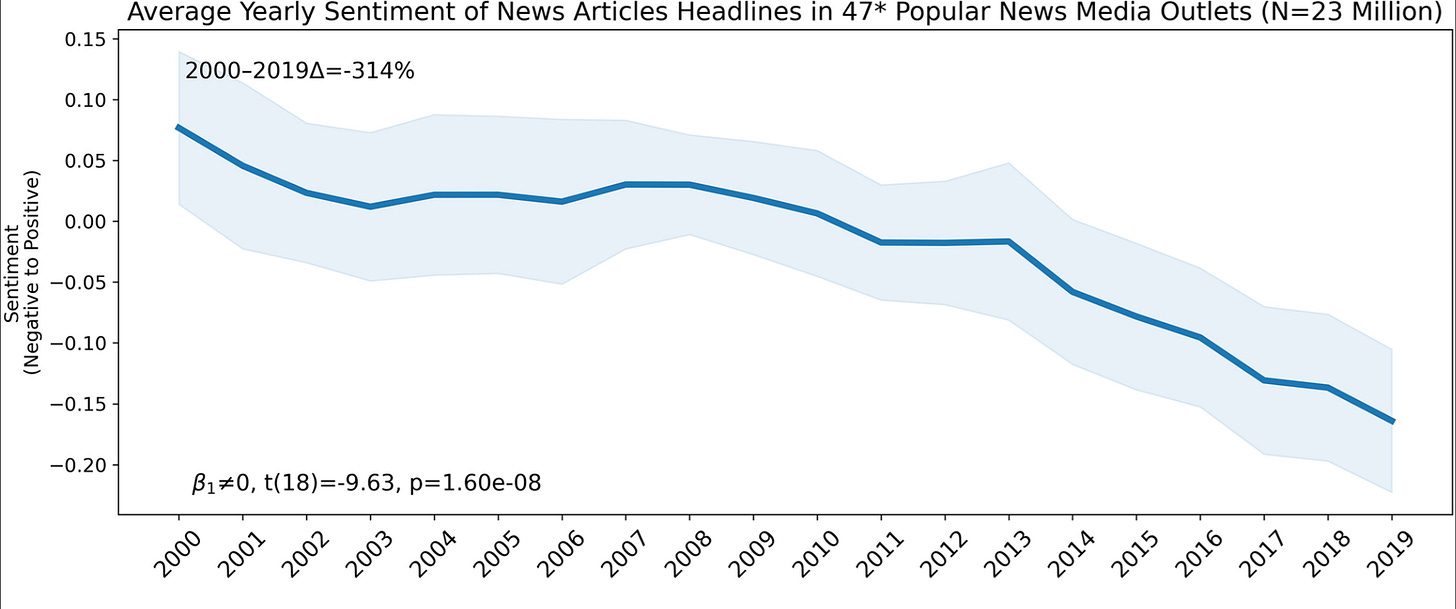

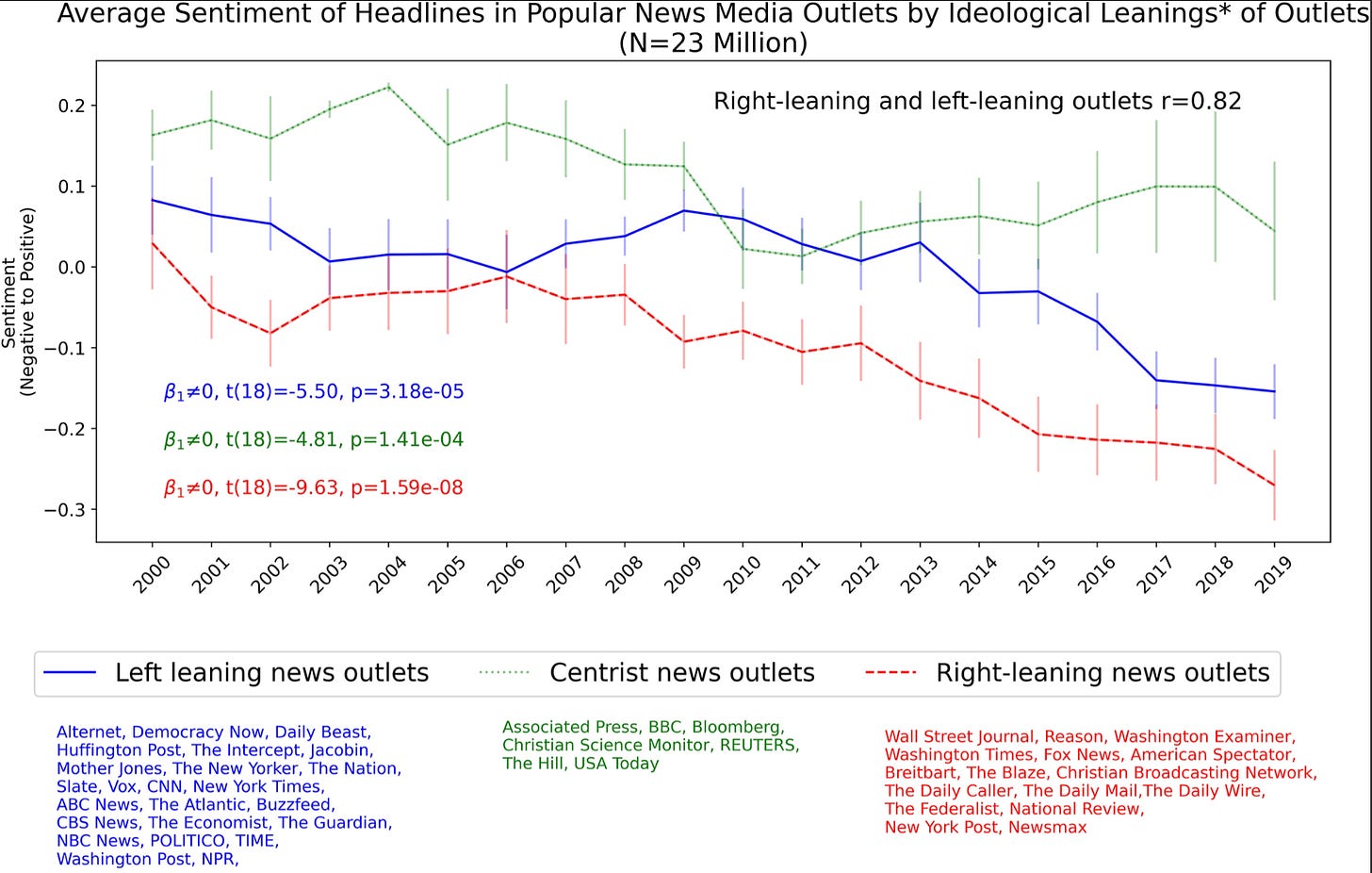

In a 2022 analysis of headlines from dozens of US news media outlets found that in the past two decades, American news headlines have gotten steadily darker, with anger, fear, disgust, and sadness climbing in frequency, especially in left- and right-leaning outlets. Around 2012—that year again!—the negativity bias in news headlines accelerated.

When you decompose the results by ideology, they get even more interesting. There seem to be two inflection points. In 2008, right-leaning outlets leaned more and more into anger, distrust, and fear. In 2012, left-wing media followed and liberal media got more negative year after year.

The Past Sucked, Part I: Be glad you don’t live in Italy in the mid-500s

I consider myself an optimist, not because I think the present is so wonderful, but rather because I’m confident that the past was so terrible. I was recently reminded of the pure horribleness of our ancestors while reading about the depopulation of Europe during the Dark Ages. In his review of the book The Crowd in the Early Middle Ages by Shane Bobrycki, Pablo Scheffer writes in the London Review of Books about one of the worst times to be alive in the last few thousand years, which was Italy in the mid-500s CE.

In the late 530s, a series of volcanic eruptions sent temperatures plummeting throughout Europe, which was already grappling with plagues, food shortages, social crises, and the political fallout of the end of the Roman Empire. Rome itself, once a metropolis of more than a million people, saw its population shrink to about 30,000—about half the capacity of the Colosseum. Wars cut off the city from trade. Aqueducts were demolished, pinching off the water supply. In the 540s, the Justinianic Plague decimated the already decimated ruins of the empire. As grain harvests collapsed, starvation spread like yet another epidemic. “Cities [lie] in ruin,” Pope Gregory I wrote at the end of the sixth century. Scheffer continues:

Between 500 and 1000 there was a trend of population decline and deurbanisation, the result of a degrading climate (the cold, arid period between the volcanic winter of 536 and 660 is sometimes called the Late Antique Little Ice Age), continuous warfare and a series of plague epidemics …

All over Europe buildings stood empty. The eighth-century writer Paul the Deacon described Metz as ‘abounding with crowds’, but also noted that its old amphitheatre had been ‘given over to wild snakes’. Bath, as depicted in the Old English poem ‘The Ruin’, had been all but abandoned: ‘Hrofas sind gehrorene, hreorge torras/hringeat berofen, hrim on lime’ (’Roofs are collapsed, towers ruined/the ring-gate destroyed, rime on mortar’). The crumbling Roman buildings hint at a past so grand and distant that the poem’s speaker imagines them as enta geweorc, the work of giants.

The Past Sucked, Part II: The U.S. used to suffer from a very different housing crisis

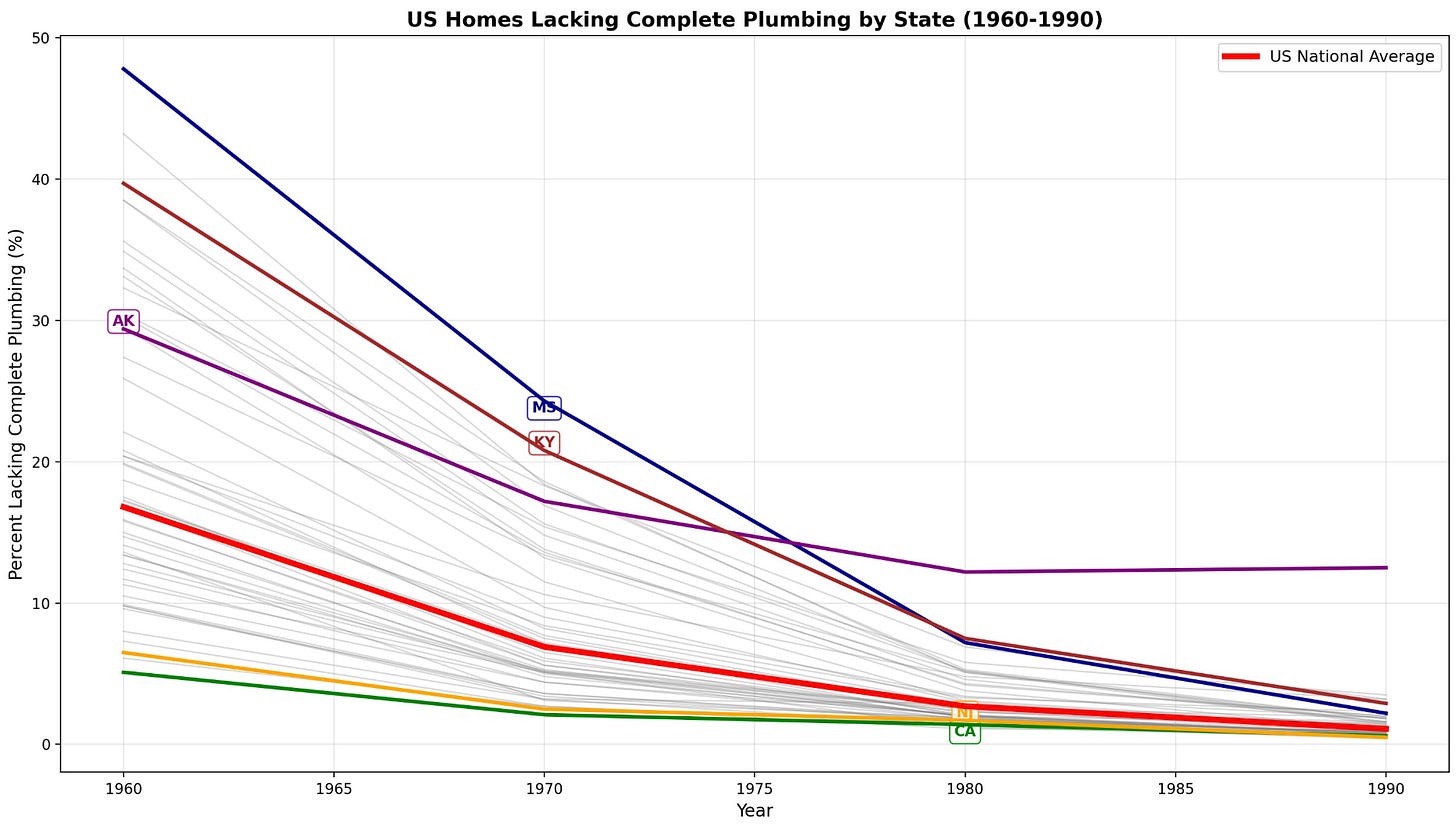

In the 1960s, less than half of homes had central heating and cooling, and more than a third of homes in several states, such as Kentucky and Mississippi, lacked complete plumbing, according to the US Census. While I acknowledge that this fact does little to placate Americans shut out of today’s hot putrid housing market, it is worthwhile to point out that yesteryear’s homes were quite literally hot and putrid.

Progress is as much about the institutions we build as it is about the truths we discover

In 1929, George Sylvester Viereck published a lengthy interview with Albert Einstein in the Saturday Evening Post. Throughout the conversation, Einstein was at his charming and epigrammatic best. When Viereck asked Einstein if he trusted “more to your imagination than to your knowledge?” the scientist replied:

I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Imagination is more important than knowledge. From this moment, a million high-school hallway posters were born.

But it’s what Einstein said a few paragraphs later that I find most profound. When Viereck asked if Einstein believed in the story of human progress, he replied that “the only progress I can see is progress in organization.” Einstein continued:

The ordinary human being does not live long enough to draw any substantial benefit from his own experience. And no one, it seems, can benefit by the experiences of others. Being both a father and teacher, I know we can teach our children nothing. We can transmit to them neither our knowledge of life nor of mathematics. Each must learn its lesson anew.”

What a gorgeous insight. A pessimist could take Einstein to be commenting on the futility of education or the inability of each generation to learn from the previous one’s mistakes. An optimist might take him to be instructing each generation to cherish the virtue of institutional renewal—to always be looking for ways to build fresh ways to organize human ingenuity to understand and improve the world. The internet is cheek to jowl with idealists who claim to be fighting for a better world, but who among them is actually building institutions to amplify their idealism? I like the idea that all human progress requires “progress in organization,” especially since so much of my work, including in Abundance, is about the ways that our institutions and organizations lock us into the past rather than allow us to build the future.

Great art can save lives.

We’ll close with one of the finer letters to the editor you’ll read, from the Times of London, on the occasion of the death of playwright Tom Stoppard.

“Saved by Stoppard”: Sir, In 1993 my wife and I went to see the first production of Arcadia by Tom Stoppard (obituary, Dec 1), and in the interval I experienced a Damascene conversion. As a clinical scientist I was trying to understand the enigma of the behaviour of breast cancer, the assumption being that it grew in a linear trajectory spitting off metastases on its way. In the first act of Arcadia, Thomasina asks her tutor, Septimus: “If there is an equation for a curve like a bell, there must be an equation for one like a bluebell, and if a bluebell, why not a rose?” With that Stoppard explains chaos theory, which better explains the behaviour of breast cancer. At the point of diagnosis, the cancer must have already scattered cancer cells into the circulation that nest latent in distant organs. The consequence of that hypothesis was the birth of “adjuvant systemic chemotherapy”, and rapidly we saw a striking fall of the curve that illustrated patients’ survival. Stoppard never learnt how many lives he saved by writing Arcadia. - Michael Baum, Professor emeritus of surgery; visiting professor of medical humanities, UCL

Re: TikTok.

I’ve noticed a weird trend where scrolling short form media alone-together has become a social trend. I work as a firefighter and we eat our meals communally. While the eating portion has continued to be social, the lingering time has become a lot of folks scrolling on their phones then sharing something they found funny or interesting with the rest of the group. I don’t have TikTok or Reels on my phone, yet I find myself sucked into other people’s algorithms by proximity and social bonding.

I can see the appeal/compulsion which is why I don’t have these apps, but it does become harder to avoid. I suppose we’re all melting together.

On item 23 and optimism: being optimistic/pessimistic about the future is less about the actual state of things than the (perceived) direction of change. A lot of people hold a bleak view not necessarily because they believe things to be better in plague-ridden Europe, but because they expect things mostly to get worse from now on. And, in fact, if you read most of the points here, it's hard to refute them. Sure, there are some new drugs for tackling obesity, but people don't read, don't party, don't have a religious community, houses, and jobs. And AI is getting exponentially better and, if we grapple with the reality, will probably outpace humans in middle-class white-collar jobs soon enough. A lot of them would really like to change places with their parents! I think a case for optimist can be made, but it should be a bit stronger and more cohesive than the 'child mortality fell in Africa' and 'at least there is no black plague and Mongol hordes around anymore' arguments that we so often see being made.