Are Young People Screwed?

It seems like everyone has suddenly agreed that young Americans have never had it worse. Let's investigate.

Capitalism “isn’t working for young people,” the venture capitalist Peter Thiel told The Free Press this week. The statement was as blunt as the source was surprising. Thiel, a staunchly pro-market techno-libertarian, is not commonly confused for Trotsky. And yet here he is, saying, and I quote directly here, “if you proletarianize the young people, you shouldn’t be surprised if they eventually become communist.”

Thiel isn’t the only conservative who’s decided that young people are getting a raw deal. In a viral report on the federal government’s far-right Gen Z cohort, the writer Rod Dreher quoted one young Republican explaining that Zoomers are rapidly becoming anti-Semitic and nihilistic on account of “his generation is so utterly screwed.” Dreher continued:

The problems are mostly economic and material, in his view (and this is something echoed by other conversations). They don’t have good career prospects, they’ll probably never be able to buy a home, many are heavily indebted with student loans that they were advised by authorities to take out, and the idea that they are likely to marry and start families seems increasingly remote.

It’s generally inadvisable to treat anecdotes and op-eds as data points. But in this case, the evidence of young people feeling screwed extends beyond these testimonies. Hiring is slowing down. Youth unemployment is going up. The market for first-time homebuyers sucks. When young people say that they’ll never be able to afford the American Dream, and when their votes reveal that affordability anxiety is reshaping our politics, we should take their statements and ballots with the utmost seriousness.

But on closer examination, the “young people are screwed” narrative is only true enough to be dangerous. Some of the evidence behind it is dead-on. Much of it is incomplete or incorrect. Trust me that I know exactly how annoying it is for a middle-aged guy to “actually…” young people who say they’re struggling. So, I thought I would try to do the fairest thing: Provide a rigorous, highly visual, one-stop evaluation of the argument, illustrating both the strongest case for and the strongest case against.

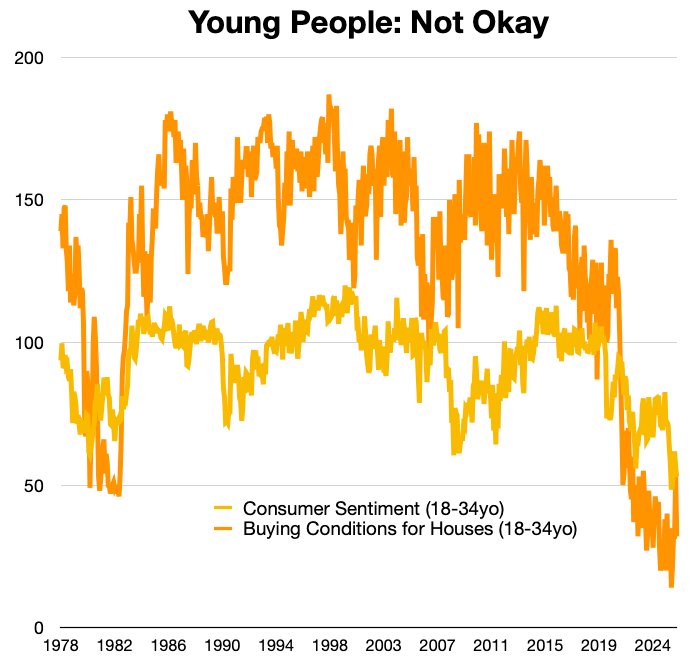

Let’s start by actually listening to young people. What are they saying about the economy?

That it sucks, basically. Since 1978, the Survey of Consumers, which is published by the University of Michigan, has asked people how they feel about consumer conditions. In the last few years, sentiment among young people has puked. Among people between 18 and 34 years old, consumer sentiment is near its all-series low—worse than the painful end of stagflation, worse than the Great Recession, and worse than the pandemic. Buying conditions for houses have fallen off a cliff. You simply cannot look at this picture and say young people think this economy is good for them, or that it’s a good time to buy stuff.

And what’s the best case that they’re right?

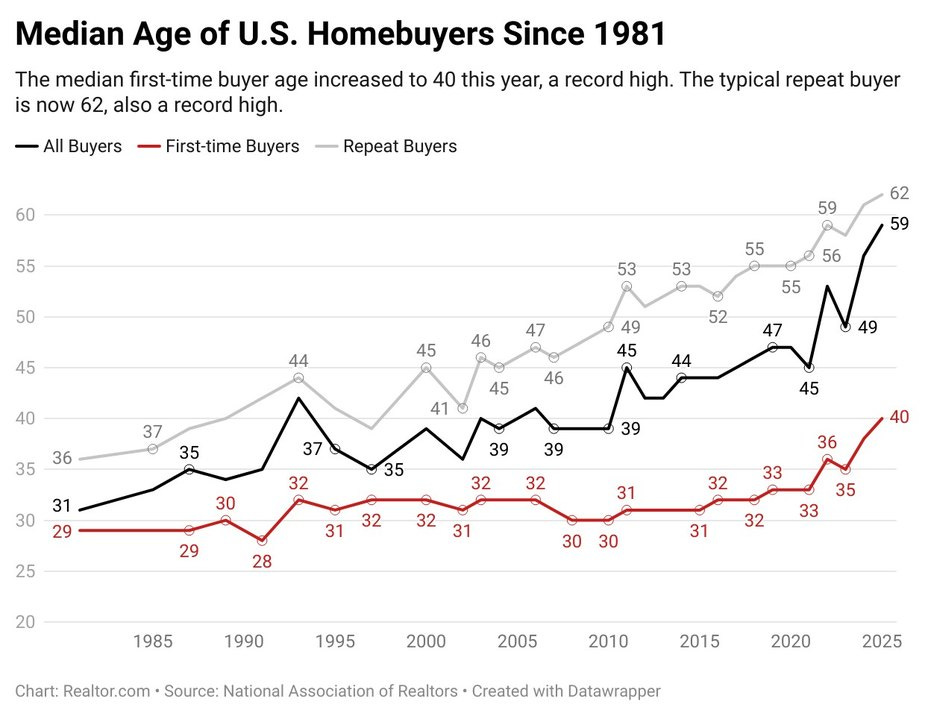

Let’s start with the housing market. This might be the worst time to be a first-time homebuyer in decades. The Great Recession produced a weak decade of construction in the 2010s. In 2020 and 2021, the pandemic struck, and as Americans with savings looked to assuage their cabin fever by buying bigger houses, the race to the suburbs sent home prices soaring. When inflation hit, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, adding the insult of high mortgage payments to the injury of higher home prices.

The result: The average age of first-time buyers just hit 40, an all-series record, according to the National Association of REALTORS. A lot of 30somethings who would have been homebuyers in any other generation now can’t afford to own where they live. That sucks.

How terrible is the labor market for young people, really?

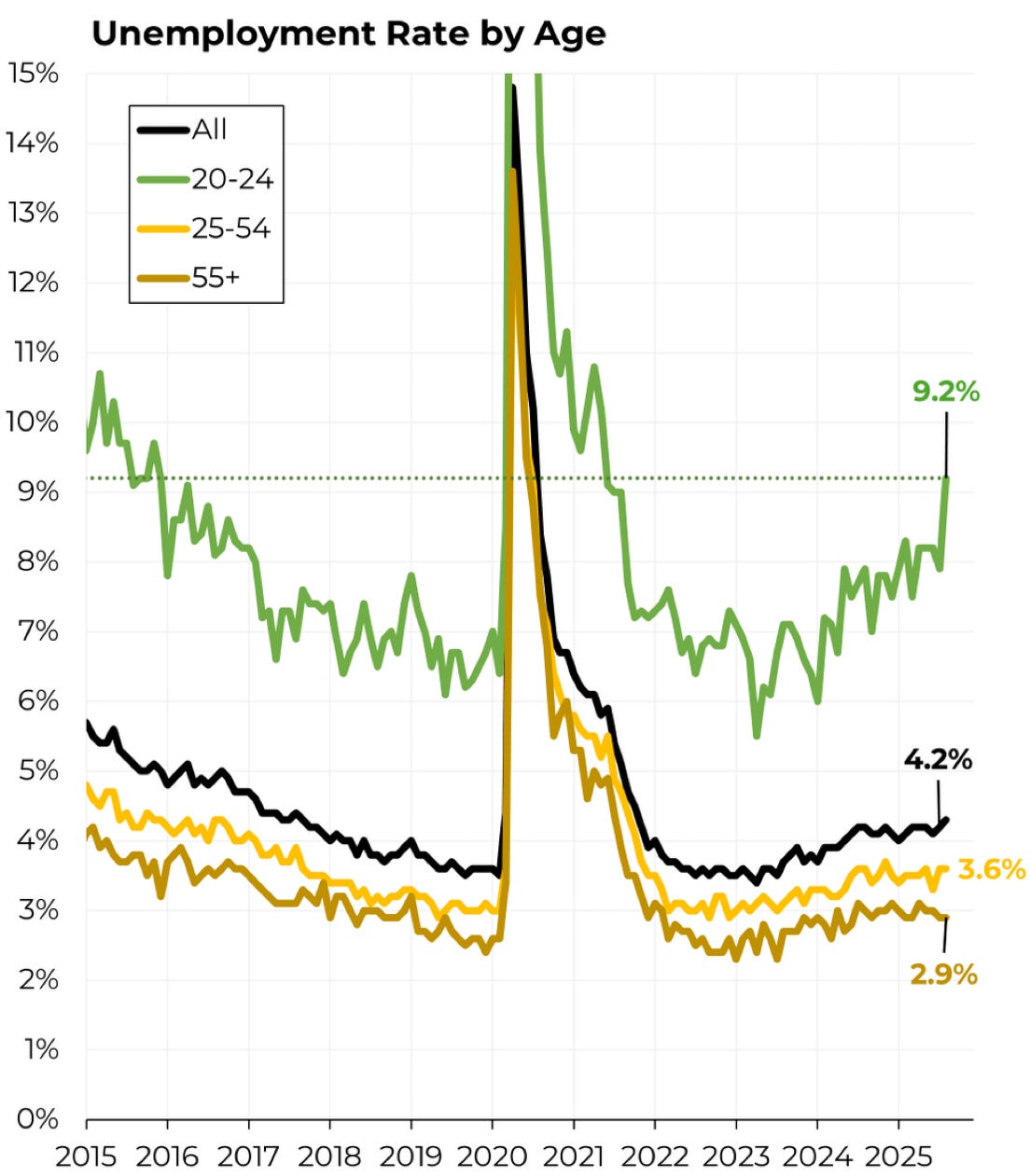

Well, it’s definitely not good. Hiring has been declining for years. The unemployment rate for Americans between 20 and 24 just hit a ten-year high (excluding the pandemic).

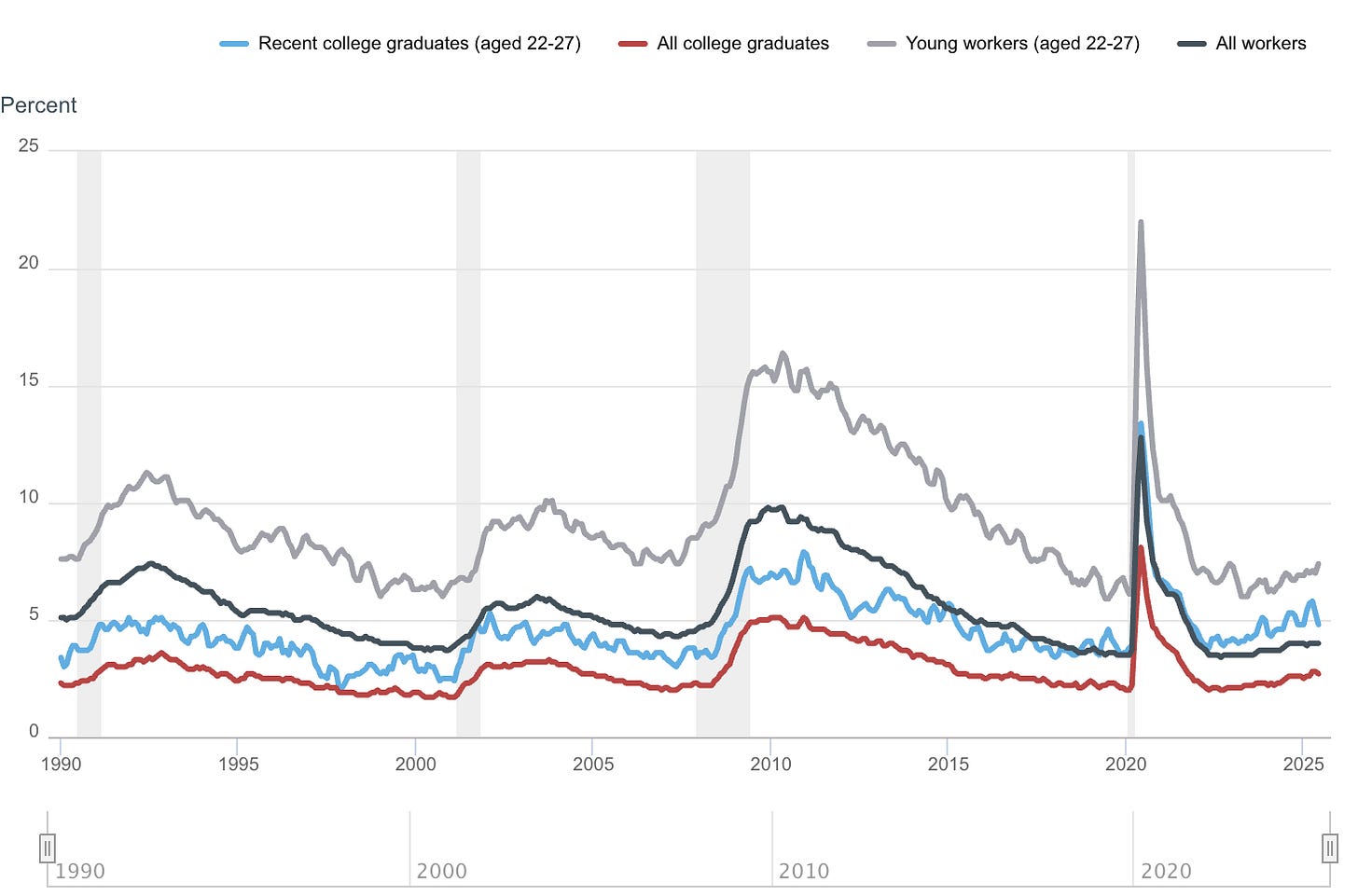

Meanwhile, in a strange twist, unemployment for young college graduates seems to be rising unusually quickly. The following chart comes from the New York Fed. In the last 40 years, the light blue line (the unemployment rate for recent college graduates between 22 and 27) is below the dark blue line (the unemployment rate for all workers). But in the last few years, that’s flipped. By this measure, at least, young college graduates seem to be having an unusually difficult time finding work.

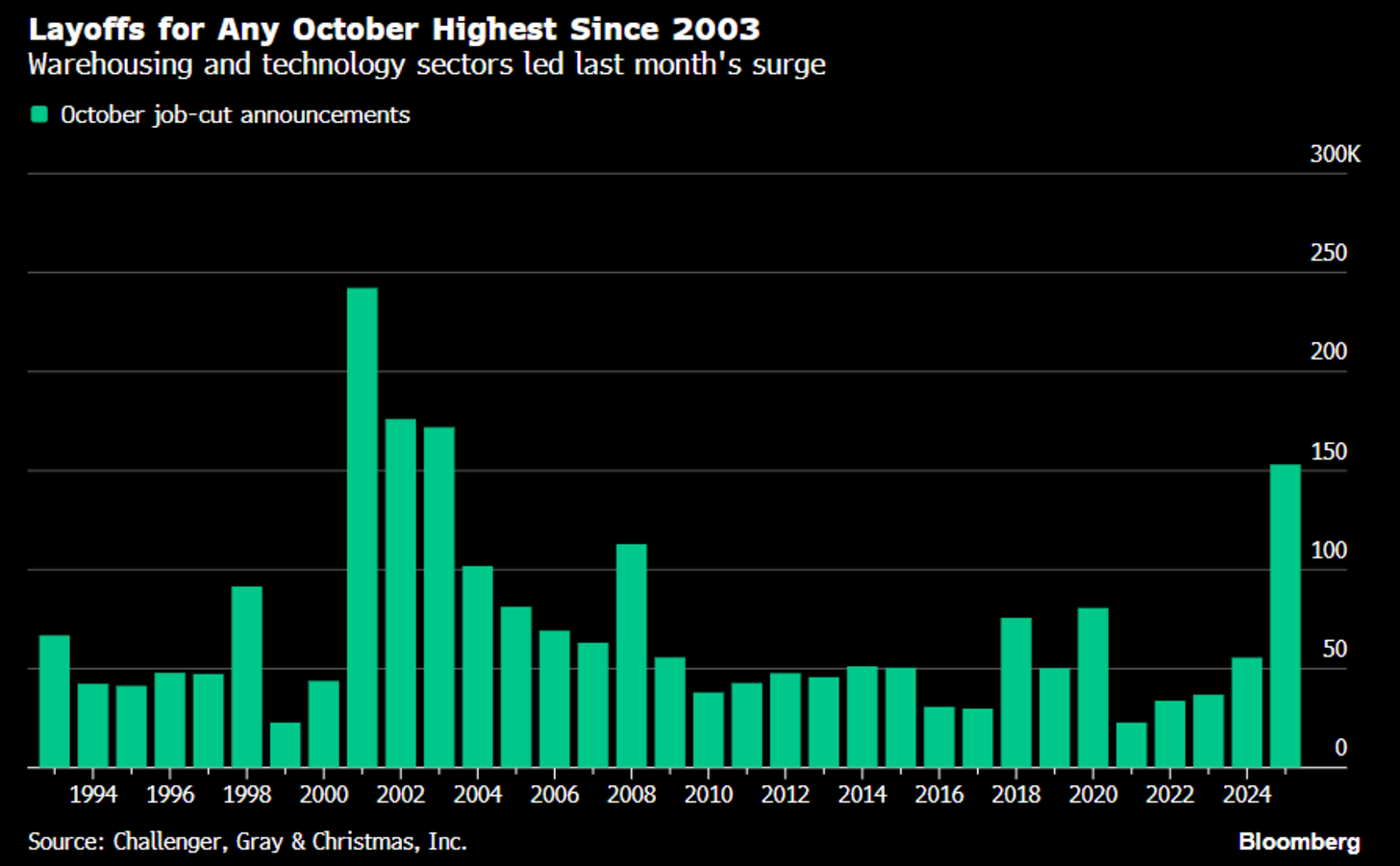

The government shutdown has left us in a bit of a dead zone when it comes to official unemployment statistics, but (slightly less reliable) private-sector measures suggest that layoffs have accelerated in the last few weeks. Challenger, Gray & Christmas recently reported that more Americans were laid off last month than any other October in more than 20 years.

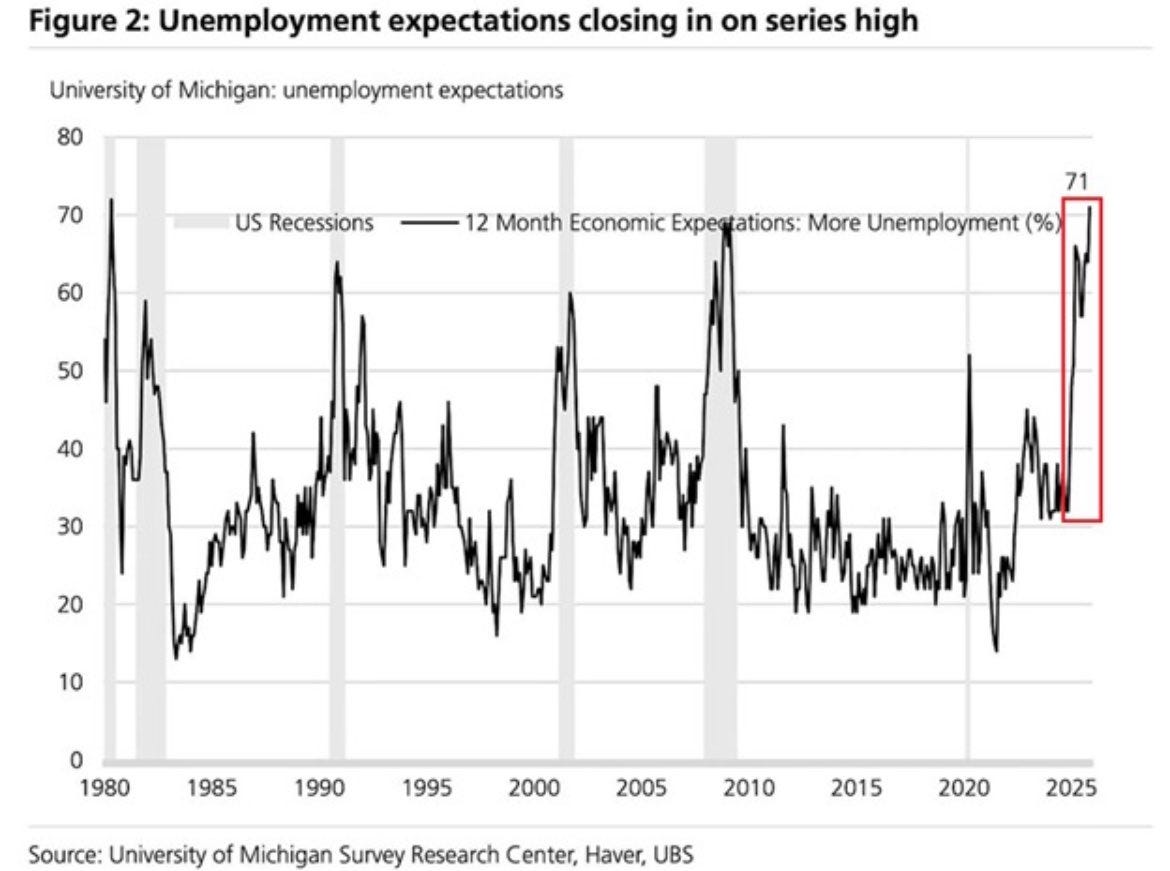

Things aren’t great, and Americans expect the labor situation to get even worse. Unemployment expectations—as measured by our friends at the University of Michigan—have surged in the last year. That is, a significant share of Americans now expects the job market to get worse in the next 12 months, as sticky inflation, slow growth, and the rise of generative AI continue to put pressure on the workforce.

What’s the best evidence that AI is taking jobs from young people?

There is not much high-quality data suggesting that ChatGPT and its ilk are displacing jobs at a massive scale, but there is some empirical evidence that the occupations that are most ChatGPT-able are hiring fewer young people than we’d otherwise expect.

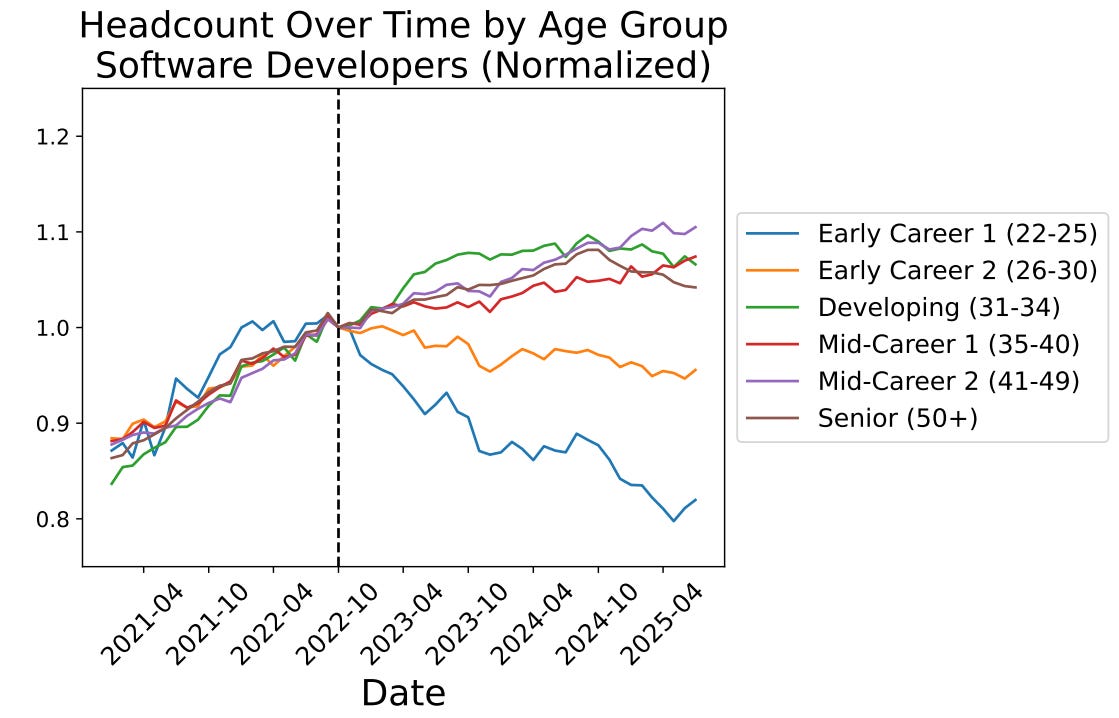

This summer, a group of economists from Stanford found that “early-career workers (ages 22-25) in the most AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent relative decline in employment,” while hiring for other roles has “remained stable or continued to grow.” For example, some software teams have found that tools from Anthropic and OpenAI help them do more work faster, which might lead one to believe that tech companies don’t need as many young coders. In fact, as the next graph from the Stanford paper shows, hiring for young software developers has meaningfully slowed down since November 2022, when ChatGPT was released.1

That sounds definitive: Young people: totally screwed. Are we done here?

The best stories, like the best conspiracy theories, are made of half-truths. Zero-truth stories don’t stick. Without a hook into reality, narratives disintegrate on contact with their audience. But full-truth accounts are often messy, nuanced, and too on-the-one-hand-but-on-the-other-hand to make for a clean story. This is my way of getting ready to tell you that the “young people are screwed” narrative is correct enough to move news cycles and political cycles, but it’s woefully incomplete as a description of economic reality. According to the best figures we have, today’s young people—and this will feel like a surprise or an outright insult to various readers—are meaningfully richer than previous generations.

In fact, one of the viral charts from above—perhaps the most viral chart from above—might just be completely wrong.