The Democrats Have a New Winning Formula

The affordability theory of everything

To understand what just happened in this week’s elections—notably Zohran Mamdani’s win in New York City, Mikie Sherrill’s win in New Jersey, and Abigail Spanberger’s win in Virginia—I think it’s useful to wind back the clock five years.

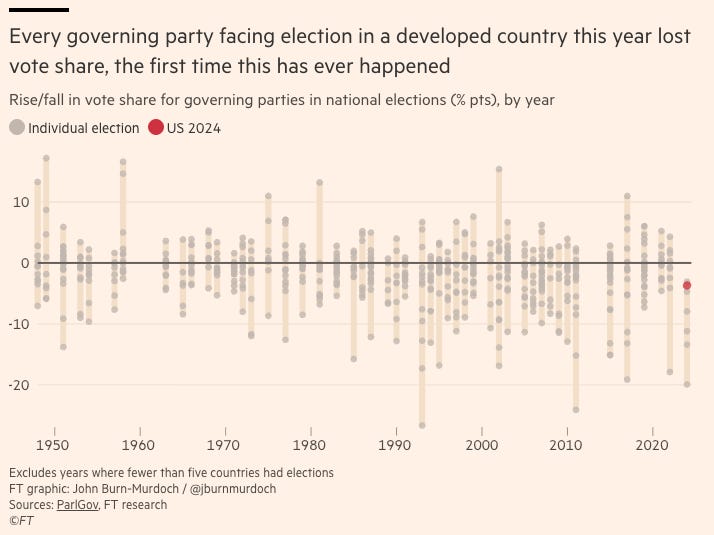

In 2020, Joe Biden won by promising that he could restore normalcy to American life. That did not happen. As the biological emergency of the pandemic (death) wound down, the economic emergency of the pandemic (inflation) took off. An affordability crisis broke out around the world. The public revolted. Last year, practically every incumbent party in every developed country lost ground at the ballot box, as the Financial Times reported.

So it went in the U.S. In 2024, Trump won an “affordability election.” I’m calling it that, because affordability is what Trump’s voters said they wanted more of. Gallup found that the economy was the only issue that a majority of voters considered “extremely important.” A CBS analysis of exit poll data found that “8 in 10 of those who said they were worse off financially compared to four years ago backed Trump.” The AP’s 120,000-respondent VoteCast survey found that voters who cited inflation as their most important factor were almost twice as likely to back Trump.

So Trump won. And, for the second straight election, the president violated his mandate to restore normalcy. Elected to be an affordability president, Trump governed as an authoritarian dilettante. He raised tariffs without the consultation of Congress, openly threatened comedians who made jokes about him, pardoned billionaires who gave his family money, arrested people without due process, oversaw the unconstitutional obliteration of the federal government workforce, and, with the bulldozing of the White House East Wing, provided an admirably vivid metaphor for his general approach to governance, norms, and decorum.1

A recent NBC poll asked voters whether they thought the president had lived up to their expectations for wrestling inflation to the ground and improving cost of living. Only 30 percent said yes. It was the his lowest number for any issue polled. The affordability issue, which seemed to be a rocket exploding upwards 12 months ago, now looks more like a bomb to which the Republican Party finds itself tightly strapped.

Big Affordability Tent

So again, for the second straight year, we have an affordability election on our hands.

On the surface, Mamdani, Spanberger, and Sherrill emerged victorious in three very different campaigns. Mamdani defeated an older Democrat in an ocean-blue metropolis. In Virginia, Spanberger crushed a bizarre Republican candidate in a state that was ground zero for DOGE cuts. In New Jersey, Sherrill—whose victory margin was the surprise of the evening—romped in a state that had been sliding toward the Republican column.

Despite these cosmetic differences, what unified the three victories was the Democratic candidate’s ability to turn the affordability curse against the sitting president, transforming Republicans’ 2024 advantage into a 2025 albatross. Here’s Shane Goldmacher at the New York Times:

Democratic victories in New Jersey and Virginia were built on promises to address the sky-high cost of living in those states while blaming Mr. Trump and his allies for all that ails those places. In New York City, the sudden rise of Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, the democratic socialist with an ambitious agenda to lower the cost of living, put a punctuation mark on affordability as a political force in 2025.

Each candidate arguably got more out of affordability than any other approach. Mamdani’s focus on cost of living in New York—which included some genuinely brilliant ads on, for example, “halalflation” and street vendor permits—has been widely covered. Less ballyhooed, but just as important, is that Spanberger and Sherrill also found that the affordability message had the biggest bang-for-buck in their own advertisements. An analysis shared with me by the polling and data firm Blue Rose Research found that “the best-testing ads in both Virginia and New Jersey focused on affordability, tying rising costs to Trump and Congressional Republicans.”

Last night showed what affordability can be for the Democratic Party. Not a policy, but a prompt, an opportunity for Democrats to fit different messages under the same tentpole while contributing to a shared national party identity: The president’s a crook, and we care about cost-of-living. In New York City, Mamdani won renters by 24 percentage points with a specific promise: Freeze the Rent. In New Jersey, Sherrill won with a Day 1 pledge to declare a state of emergency on utility costs, which would allow her to halt rates and delete red tape that holds back energy generation. (The opening line of her mission statement: “Life in New Jersey is too expensive and every single New Jerseyan who pays the bills knows it.”) In Virginia, Spanberger went another way, relentlessly blaming rising costs on Trump, as in the advertisement below.

What’s notable isn’t just what the above messages have in common but what they don’t have in common. Sherrill focused on utility costs, while Mamdani focused on rent. Mamdani ran a socialist campaign to energize a young left-wing electorate, while Spanberger’s task was to win a purple state following an outgoing Republican governor. Each candidate answered the affordability prompt with a tailored message fit to electorate. Affordability is a big tent. So big, in fact, that David Shor, a Democratic pollster sometimes accused by the left of advancing centrist popularism, acknowledged on Tuesday that his firm worked gladly with Mamdani on his campaign. “Zohran’s relentless disciplined campaign was truly impressive,” Shor wrote. “He brought every message and issue back to the cost of living and built a model for what bringing attention to a positive affordability message can look like.”

The affordability message was especially successful at bringing young voters back to the Democratic fold. After the 2024 election, I worried that young people were listing to the right. Last night was not the ideal test of that theory, since off-year elections tend to have a smaller and more educated (and, therefore, more naturally anti-Trump) electorate. But it seems as if the rightward wave is now undulating to the left. The pollster John Della Volpe reported that young voters “anchored the Democratic turnaround in Virginia, where 18-29-year-olds delivered a 35-point margin for Spanberger, the largest for Democrats since 2017.

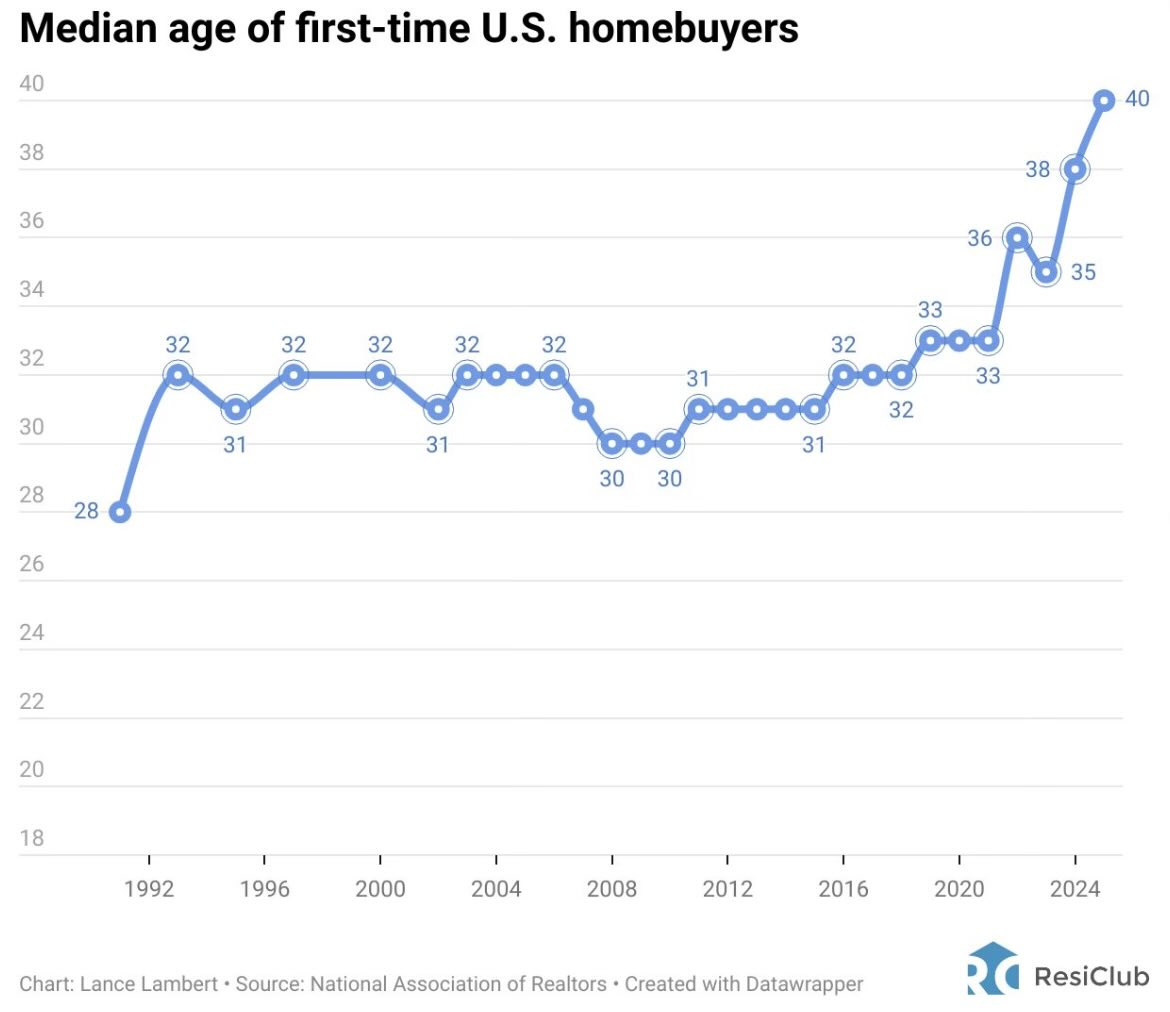

We don’t need to look far to understand why young voters would appreciate an emphasis on cost of living. Just this week, the National Association of Realtors announced that the median age of first-time US homebuyers jumped to a new record of 40. “Zohran’s campaign centered cost of living issues and he at least appeared consistently willing to look for answers wherever they may present themselves,” said Daniel Racz, a 23-year-old sports data analyst who lives in New York. “I think of his mentions of the history of Sewer Socialism, proposed trial runs of public grocery stores on an experimental basis and his past free bus pilot program showcased a political curiosity grounded in gathering information to improve his constituents’ lives.”

Amanda Litman, the co-founder and president of Run for Something, oversees a national recruitment effort to help progressives run for down-ballot office. On Tuesday, they had 222 candidates in general elections across the country. “Nearly every candidate who won an election for municipal or state legislative office was talking about affordability, especially as it relates to housing,” she said. “Housing is the number one issue we’ve seen people bring up as a reason to run for office this year.”

Politics Is About Winning But Also About What You Do If You Win

The affordability approach has several strengths. Because it is a prompt rather than a policy, it allows Democrats to be organized in their thematic positioning but heterodox in their policies. A socialist can run on affordability in a blue city and win with anti-corporate policies, and a moderate can run on affordability in a red state and win with something very different. At a time when Democrats are screaming at each other online and off about populism versus moderation, the affordability tent allows them to be diverse yet united: They can run on tying Trump to the affordability crisis while crafting messages fit for their respective electorates. “The Democratic Party does not need to choose to be one thing,” Ezra Klein said last week. “It needs to choose to be more things.” Centering affordability makes it easier for Democrats to choose to be more things.

This next bit is a bit speculative, and it might be entirely wrong, but I think another advantage of centering affordability is that it is easier for members of a political coalition to negotiate on material politics than on postmaterial politics. Put differently, economic disagreements within a group are more likely to produce debate and even compromise while cultural disagreements are more likely to produce purity tests and excommunication. If a YIMBY left-centrist and a democratic socialist disagree about the right balance of price controls and supply-side reforms to reduce housing inflation in New York City, that might lead to a perfectly pleasant conversation. But it’s my strong sense that perfectly pleasant conversations between political commentators about, say, ICE deportations or trans women in college sports are not as common. If this is true—and, again, I’m sort of thinking out loud here—it would suggest that the spotlight of Democratic attention shifting toward affordability might automatically and naturally ameliorate the culture of progressive purity tests in a way that would make for a bigger tent that tolerates a wider range of views.

Affordability politics also poses a distinct challenge, At the national level, Democrats do not have their hands on the price levers, and they won’t for at least four more calendar years, and even if they did, the best ways to reduce the national price level involve higher interest rates (painful), meaningful spending cuts (excruciating), or a national tax increase (dial 911). Even at the local level, affordability politics in an age of elevated inflation, rapidly growing AI, and complex impediments to affordable housing2 can easily promise too much—or, to be more exact, it can offer a set of dangerously falsifiable promises. Affordability politics thrives because of the specificity and clarity of its pledge: Prices are too high, I’ll fix it if you give me power. But politics isn’t just about the words you put on your bumper stickers, it’s about what you do if the bumper stickers work. Building houses takes time, even after you reduce barriers and improve financing, and the effect on residential prices can take even longer. Energy inflation is a bear of a problem, with transmission prices rising and data center construction exploding. After we learn whose affordability messages win at the ballot box, we’ll learn whose affordability policies actually work and keep them in office.

One year ago today, after Trump won his second election, I wrote that if there was cold comfort for the sorry state of the Democratic Party, it was this:

We are in an age of politics when every victory is Pyrrhic, because to gain office is to become the very thing—the establishment, the incumbent—that a part of your citizenry will inevitably want to replace. Democrats have been temporarily banished to the wilderness by a counterrevolution, but if the trends of the 21st century hold, then the very anti-incumbent mechanisms that brought them defeat this year will eventually bring them back to power.

Affordability is good politics, and a Democratic Party that focuses on affordability at the national level, and supports motley approaches to solving the cost-of-living crisis at the local level, is in a strong position going into 2026. But saying the word affordability over and over doesn’t necessarily guarantee good policy outcomes. In fact, it doesn’t guarantee anything. Which is why at some point on the road back to relevance, the Democratic Party needs to become obsessed with not only winning back power but also governing effectively in the places where they have it.

In fact, you might say the president has spent the last few months doing just about everything except focusing on the very affordability crisis that brought him to office. In a parallel universe, Trump might have announced on Day One of his presidency that he would do everything in his power to reduce housing prices—and then actually do that. Instead, he immediately raised tariffs on imported lumber and drywall, driving up the cost of housing construction, and meanwhile drove net immigration into the ground, when the residential construction industry is more than 20 percent foreign-born. Trump might have announced Day Two that he would do everything in his power to reduce the cost of electricity—and then actually done that. Instead, the cost of transformers and wires continues to rise faster than inflation, and the administration has bizarrely threatened to block various sources of renewable energy generation even as it pushes for the construction of more energy-thirsty data centers to power our AI boom.

Just for starters: High interest rates, financing issues with private capital getting sucked over to AI infrastructure, declining foreign-born population, an absolutely moribund resale market, local zoning rules, permitting issues, environmental review, and slow productivity growth in residential construction possibly due to the inability of successful innovative companies to scale nationally.

Affordability and abundance seem synonymous, given how supply and demand works. Which makes me worried that the same issues that plague abundance agendas are going to plague affordability agendas: fealty to unions and special interest groups.

This is a great analysis of the outcome and driving force from these disparate elections. I guess I would offer two critiques: regarding Trump not focusing on affordability, I would say he is but not in ways Democrats would recognize. Removing illegal immigrants will bring down home prices if simple supply/demand economics is to be believed. Focusing on energy production has brought down gas prices which will reduce costs. And the tariff theory is that more manufacturing can be done in this country, bringing with it more jobs, higher wages and better economic stability and equality. Will these materialize? I’m not sure, but I think that’s the theory and we’ll see if things play out that way. That said, they’re longer-term market effects, not overnight policy wins. At some point they need to result in the benefits Trump is promising, obviously, but I think it needs more time to play out, personally.

I also was curious whether ‘no enemies to the left’ is a thing? For me, as an independent but more of a small government person, Mamdani and the rise of the DSA terrifies me. I equate socialism with Nazism, both are authoritarian governments that lead to death and destruction. I just don’t see how we’ve gotten to the point in this country that socialism is normalized and acceptable.