How to Sound Like an Expert in Any AI Bubble Debate

There are 12 statistics, factoids, and studies that dominate every discussion about whether artificial intelligence is a bubble. Here's a deep-dive into all 12 arguments

I’m excited to publish this post co-authored with Timothy Lee, one of my favorite writers on technology and artificial intelligence. His Substack Understanding AI is a fantastic guide to how AI works as a technology and a business.

In the last few weeks, something’s troubled and fascinated us about the national debate over whether artificial intelligence is a bubble. Everywhere we look and listen, experts are citing the same small number of statistics, factoids, and studies. The debate is like a board game with a tiny number of usable pieces. For example:

Talk to AI bears, and they’ll tell you how much Big Tech is spending

Talk to AI bulls, and they’ll tell you how much Big Tech is making

Talk to artificial general intelligence believers, and they’ll quote a famous study on “task length” by an organization called METR

Talk to AGI skeptics, and they’ll quote another famous study on productivity, also by METR

Last week, we were discussing how one could capture the entire AI-bubble debate in about 12 statistics that people just keep citing and reciting — on CNBC, on tech podcasts, in Goldman Sachs Research documents, and at San Francisco AI parties. Since everybody seems to be reading and quoting from the same skinny playbook, we thought: What the hell, let’s just publish the whole playbook!

If you read this article, we think you’ll be prepared for just about every conversation about AI, whether you find yourself at a Bay Area gathering with accelerationists or a Thanksgiving debate with Luddite cousins. We think some of these arguments are compelling. We think others are less persuasive. So, throughout the article, we’ll explain both why each argument belongs in the discussion and why some arguments don’t prove as much as they claim. Read to the end, and you’ll see where each of us comes down on the debate.

Let’s start with the six strongest arguments that there is an AI bubble.

All about the Benjamins

WHEN THEY SAY: Prove to me that AI is a bubble

YOU SAY: For starters, this level of spending is insane

When America builds big infrastructure projects, we often over-build. Nineteenth-century railroads? Overbuilt, bubble. Twentieth-century internet? Overbuilt, bubble. It’s really nothing against AI specifically to suggest that every time US companies get this excited about a big new thing, they get too excited, and their exuberance creates a bubble.

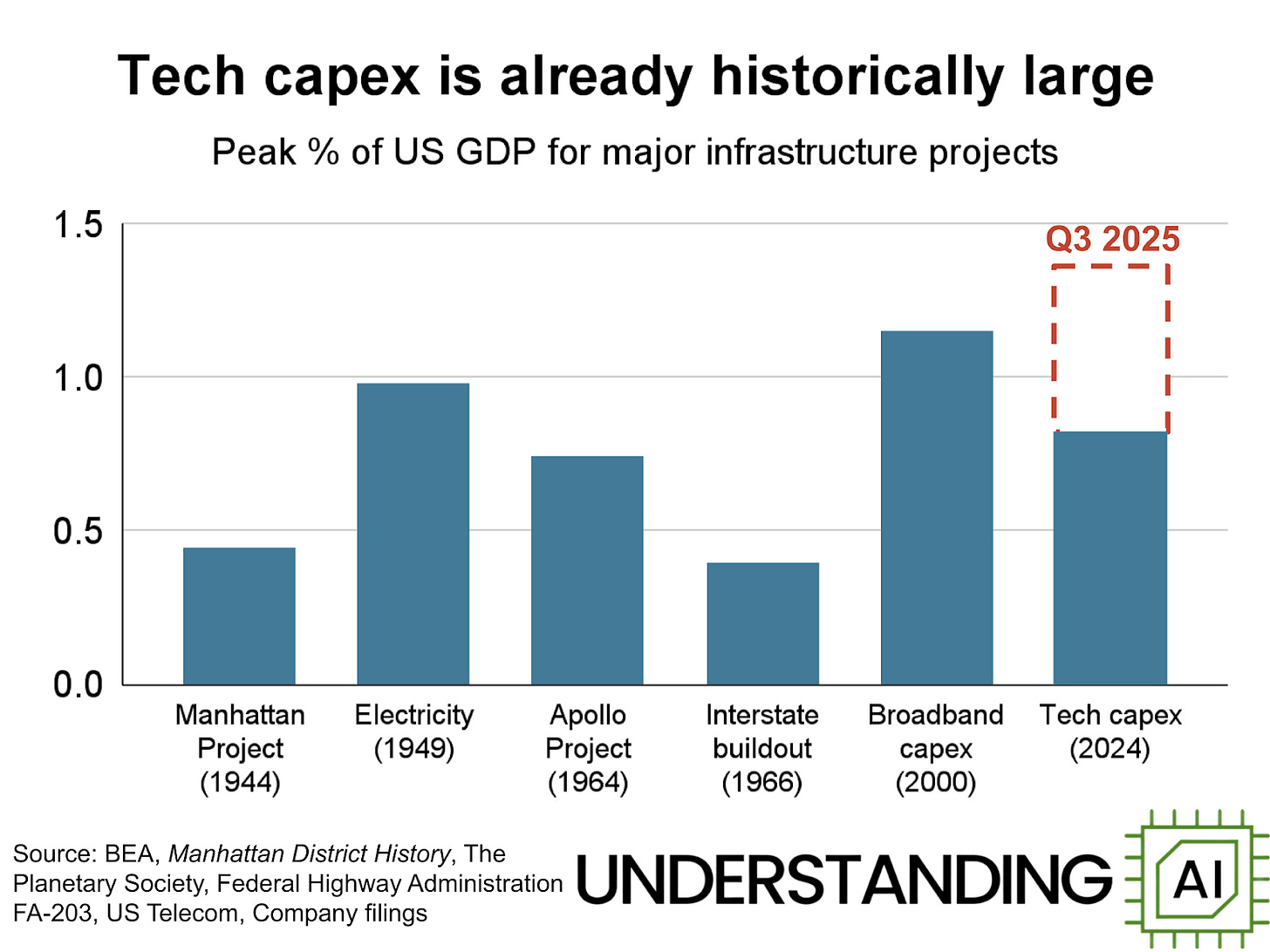

Five of the largest technology giants — Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Oracle — had $106 billion in capital expenditures in the most recent quarter. That works out to almost 1.4% of gross domestic product, putting it on par with some of the largest infrastructure investments in American history.

This chart was originally created by Understanding AI’s Kai Williams, who noted, “not all tech capex is spent on data centers, and not all data centers are dedicated to AI. The spending shown in this chart includes all the equipment and infrastructure a company buys. For instance, Amazon also needs to pay for new warehouses to ship packages.”

Still, AI accounts for a very large share of this spending. Amazon’s CEO, for example, said last year that AI accounted for “the vast majority” of Amazon’s recent capex. And notice that the last big boom on the chart — the broadband investment boom of the late 1990s — ended with a crash. AI investments are now large enough that a sudden slowdown would have serious macroeconomic consequences.

Money for nothing

WHEN THEY SAY: But this isn’t like the dot-com bubble, because these companies are for real

YOU SAY: I’m not so sure about that…

“It feels like there’s obviously a bubble in the private markets,” said Demis Hassabis, the CEO of Google DeepMind. “You look at seed rounds with just nothing being [worth] tens of billions of dollars. That seems a little unsustainable. It’s not quite logical to me.”

The canonical example of zillions of dollars for zilch in product has been Thinking Machines, the AI startup led by former OpenAI executive Mira Murati. This summer, Thinking Labs raised $2 billion, the largest seed round in corporate history, before releasing a product. According to a September report in The Information, the firm declined to tell investors or the public what they were even working on.

“It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” one investor who met with Murati said. “She was like, ‘So we’re doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can’t answer any questions.’”

In October, the company launched a programming interface called Tinker. I guess that’s something. Or, at least, it better be something quite spectacular, because just days later, the firm announced that Murati was in talks with investors to raise another $5 billion. This would raise the value of the company to $50 billion—more than the market caps of Target or Ford.

When enterprises that barely have products are raising money at valuations rivaling 100-year-old multinational firms, it makes us wonder if something weird is going on.

Reality check

WHEN THEY SAY: Well, AI is making me more productive

YOU SAY: You might be deluding yourself

One of the hottest applications of AI right now is programming. Over the last 18 months, millions of programmers have started using agentic AI coding tools such as Cursor, Anthropic’s Claude Code, and OpenAI’s Codex, which are capable of performing routine programming tasks. Many programmers have found that these tools make them dramatically more productive at their jobs.

But a July study from the research organization METR called that into question. They asked 16 programmers to tackle 246 distinct tasks. Programmers estimated how long it would take to complete each task. Then they were randomly assigned to use AI, or not, on a task-by-task basis.

On average, the developers believed that AI would allow them to complete their tasks 24% faster with the help of AI. Even after the fact, developers who used AI thought it had sped them up by 20%. But programmers who used AI took 19% longer, on average, than programmers who didn’t.

We were both surprised by this result when it first came out, and we consider it one of the strongest data points in favor of AI skepticism. While many people believe that AI has made them more productive at their jobs — including both of us — it’s possible that we’re all deluding ourselves. Maybe that will become more obvious over the next year or two and the hype around AI will dissipate.

But it’s also possible that programmers are just in the early stages of the learning process for AI coding tools. AI tools probably speed up programmers on some tasks and slow them down on others. Over time, programmers may get better at predicting which tasks fall into which category. Or perhaps the tools themselves will get better over time. Some of today’s most popular coding tools have been out for less than a year.

It’s also possible that the METR results simply aren’t representative of the software industry as a whole. For example, a November study examined 32 organizations that started to use Cursor’s coding agent in the fall of 2024. It found that programmer productivity increased by 26% to 39% as a result.

Infinite money glitch

WHEN THEY SAY: But AI is clearly growing the overall economy

YOU SAY: Maybe the whole thing is a trillion-dollar ouroboros

Imagine Tim makes some lemonade. He loans Derek $10 to buy a drink. Derek buys Tim’s lemonade for $10. Can we really say that Tim has “earned $10” in this scenario? Maybe no: If Derek goes away, all Tim has done is move money from his left pocket to his right pocket. But maybe yes: If Derek loves the lemonade and keeps buying more every day, then Tim’s bet has paid off handsomely.

Artificial intelligence is more complicated than lemonade. But some analysts are worried that the circular financing scheme we described above is also happening in AI. In September, Nvidia announced it would invest “up to” $100 billion in OpenAI to support the construction of up to 10 gigawatts of data center capacity. In exchange, OpenAI agreed to use Nvidia’s chips for the buildout. The next day, OpenAI announced five new locations to be built by Oracle in a new partnership whose value reportedly exceeds $300 billion. The industry analyst Dylan Patel called this financial circuitry an “infinite money glitch.”

Bloomberg made this chart depicting the complex web of transactions among leading AI companies. This kind of thing sets off alarm bells for people who remember how financial shenanigans contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.

The fear is two-fold: first, that tech companies are shifting money around in a way that creates the appearance of new revenue that hasn’t actually materialized; and second, that if any part of this financial ouroboros breaks, everybody is going down. In the last few months, OpenAI has announced four deals: with Nvidia, Oracle, and the chipmakers AMD and Broadcom. All four companies saw their market values jump by tens of billions of dollars the day their deals were announced. But, by that same logic, any wobble for OpenAI or Nvidia could reverberate throughout the AI ecosystem.

Something similar happened during the original dot-com bubble. The investor Paul Graham sold a company to Yahoo in 1998, so he had a front-row seat to the mania:

By 1998, Yahoo was the beneficiary of a de facto Ponzi scheme. Investors were excited about the Internet. One reason they were excited was Yahoo’s revenue growth. So they invested in new Internet startups. The startups then used the money to buy ads on Yahoo to get traffic. Which caused yet more revenue growth for Yahoo, and further convinced investors the Internet was worth investing in. When I realized this one day, sitting in my cubicle, I jumped up like Archimedes in his bathtub, except instead of “Eureka!” I was shouting “Sell!”

Are we seeing a similar dynamic with the data center boom? It doesn’t seem like a crazy theory.

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain

WHEN THEY SAY: The hyperscalers are smart companies and don’t need bubbles to grow

YOU SAY: So why are they resorting to financial trickery?

Some skeptics argue that big tech companies are concealing the actual cost of the AI buildout.

First, they’re shifting AI spending off their corporate balance sheets. Instead of paying for data centers themselves, they’re teaming up with private capital firms to create joint ventures known as special purpose vehicles (or SPVs). These entities build the facilities and buy the chips, while the spending sits somewhere other than the tech company’s books. This summer, Meta reportedly sought to raise about $29 billion from private credit firms for new AI data centers structured through such SPVs.

Meta isn’t alone. CoreWeave, the fast-growing AI-cloud company, has also turned to private credit to fund its expansion through SPVs. These entities transfer risk off the balance sheets of Silicon Valley companies and onto the balance sheets of private-capital limited partners, including pension funds and insurance companies. If the AI bubble bursts, it won’t be just tech shareholders who feel the pain. It will be retirees and insurance policyholders.

To be fair, it’s not clear that anything shady is happening here. Tech companies have plenty of AI infrastructure on their own balance sheets, and they’ve been bragging about that spending in earnings calls, not downplaying it. So it’s not obvious that they are using SPVs in an effort to mislead people.

Second, skeptics argue that tech companies are underplaying the depreciation risk of the hardware that powers AI. Earlier waves of American infrastructure left us with infrastructure that held its value for decades: power lines from the 1940s, freeways from the 1960s, fiber optic cables from the 1990s. By contrast, the best GPUs are overtaken by superior models every few years. The hyperscalers spread their cost over five or six years through an accounting process called depreciation. But if they have to buy a new set of top-end chips every two years, they’ll eventually blow a hole in their profitability.

We don’t dismiss this fear. But the danger is easily exaggerated. Consider the A100 chip, which helped train GPT-4 in 2022. The first A100s were sold in 2020, which makes the oldest units about five years old. Yet they’re still widely used. “In a compute-constrained world, there is still ample demand for running A100s,” Bernstein analyst Stacy Rasgon recently wrote. Major cloud vendors continue to offer A100 capacity, and customers continue to buy it.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that today’s chips will be as durable. If AI demand cools, we could see a glut of hardware and early retirement of older chips. But based on what we know today, it’s reasonable to assume that a GPU purchased now will still be useful five years from now.

A changing debt picture

WHEN THEY SAY: The hyperscalers are well-run companies that won’t use irresponsible leverage

YOU SAY: That might be changing

A common way for a bubble to end is with too much debt and too little revenue. Most of the Big Tech companies building AI infrastructure — including Google, Microsoft, and Meta — haven’t needed to take on much debt because they can fund the investments with profit. Oracle has been a notable exception to this trend, and some people consider it the canary in the coal mine.

Oracle recently borrowed $18 billion for data center construction, pushing the company’s total debt above $100 billion. The Wall Street Journal reports that “the company’s adjusted debt, a measure that includes what it owes on leases in addition to what it owes creditors, is forecast to more than double to roughly $300 billion by 2028, according to credit analysts at Morgan Stanley.”

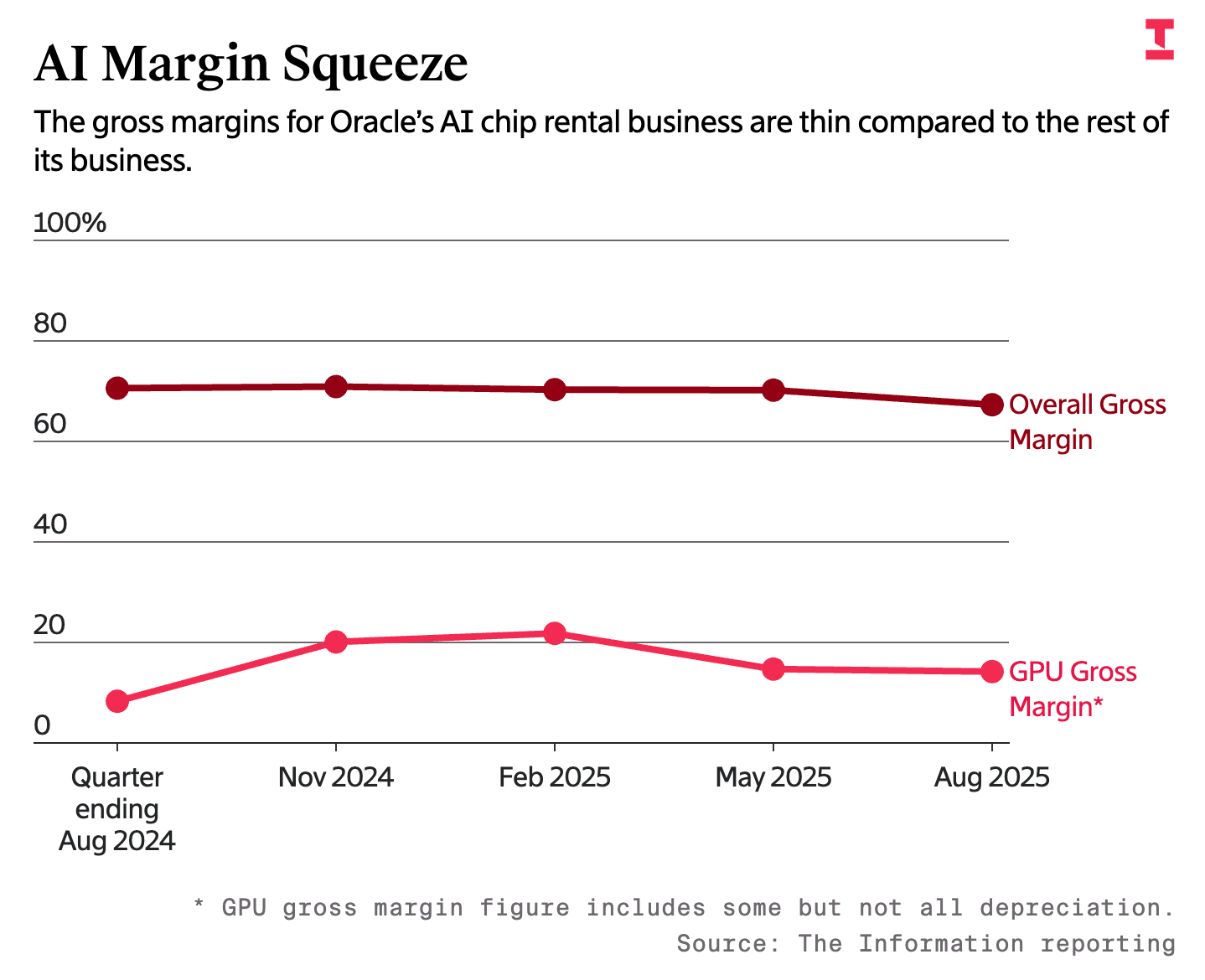

At the same time, it’s not obvious that Oracle is going to make a lot of money from this aggressive expansion. There’s plenty of demand: in its most recent earnings call, Oracle said that it had $455 billion in contracted future revenue — a more than four-fold increase over the previous year. But The Information reports that in the most recent quarter, Oracle earned $125 million on $900 million worth of revenue from renting out data centers powered by Nvidia GPUs. That works out to a 14% profit margin. That’s a modest profit margin in a normal business, and it’s especially modest in a highly volatile industry like this one. It’s much smaller than the roughly 70% gross margin Oracle gets on more established services.

The worry for AI skeptics is that customer demand for GPUs could cool off as quickly as it heated up. In theory, that $455 billion figure represents firm customer commitments to purchase future computing services. But if there’s an industry-wide downturn, some customers might try to renegotiate the terms of these contracts. Others might simply go out of business. And that could leave Oracle with a lot of debt, a lot of idle GPUs, and not enough revenue to pay for it all.