The Monks in the Casino

A brief theory of young men, "the loneliness crisis," and life in the 21st century

I. Spishak and Kyle

I want to tell you about two young men.

First, there is “Spishak,” the online pseudonym of a 28-year-old living at his parents’ home in Los Angeles. Spishak considers himself a pornosexual, which is exactly what it sounds like. He is a virgin whose carnal relations involve thousands of videos and no carbon-based life forms. As the journalist Daniel Kolitz describes in a Harper’s Magazine essay, Spishak’s room is a shrine to erotica, where 27 separate pornographic videos play simultaneously on eight tablets and three monitors. Asked about his relationships, Spishak tells Kolitz that he’s never been “good with talking to women,” and the pandemic arrested any development on that front. What most frightens Spishak about sex between two people “is the impossibility of ever knowing what’s really going on in your partner’s head.” “I just feel like it’s exhausting,” Spishak says, “for both parties.”

Second, there is Kyle, a 26-year-old who lived in Denver in 2020 when legal sports gambling arrived in Colorado. Kyle immediately opened an account with nearly every sportsbook. Then, as Jonathan Cohen writes in his book Losing Big, Kyle went on a hot streak. In one month, he gambled more than $95,000 on a salary of $65,000. He spent so much time betting on sports that he lost his job. When the unemployment checks came, he gambled those, too. When the hot streak chilled and Kyle couldn’t pay his rent, he moved back home to live with his parents in Wichita. Cut off from his friends in Denver, he gambled even more—all day and night, without sleeping, subsisting on cigarettes and beer in his bedroom. At 3 a.m. in the morning, he would look up any games that might be happening on the other end of the world: Malaysia, India, wherever. He’d bet on those, too.

Spishak and Kyle are extraordinary cases. Not every young man is addicted to pornography or gambling. But look deeper at their stories. Waylaid by the pandemic, two young men work from home and spend much of their lives alone; remaining inside, they surround themselves with computer monitors—“in many ways, [Kyle’s] life had two monitors, one for gambling and one for everything else,” Cohen writes—where they stream entertainment that allows them to avoid the messy frictions and complications of life. This is a profoundly ordinary description of being a young man in America today. When the sociologist Liana Sayer led a group of researchers to analyze leisure time in 2024, she found that one group had, by far, the most “sedentary leisure time alone”—that is, time spent sitting in a room by themselves, typically in the company of screens. It was young, unmarried men.

I’ve been thinking recently about these guys who are dating less, socializing less, and leaving their home less, while filling their media with more porn and betting parlays. They seem to prefer the financial discomfort of losing a bet to the social anxiety of being rejected on a date. They find intimacy scary and gambling exciting. They furnish their rooms like high-tech monasteries and gravitate toward media that works like a slot machine.

These young men seem to me like modern ascetics who find themselves somehow trapped on the betting floor of the economy. They are like monks, yes. But more than that: They are monks in a casino. Risk-aversion in the social sphere has combined with their risk-chasing in the market, and it’s created a genuinely berserk modern life script.

II. The American Monk

Outwardly, many of today’s young people live healthier lives than any group in decades, even centuries. They smoke less. They drink less. They use fewer drugs. They exercise more, too.

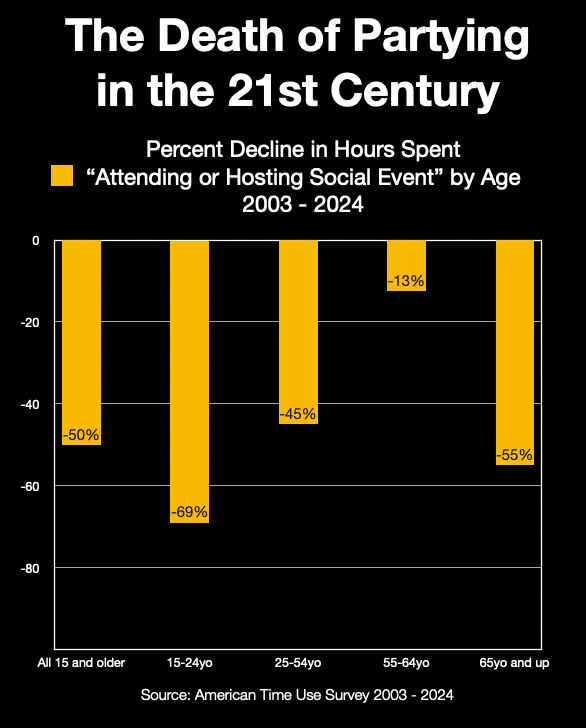

But these healthy behaviors often come at the cost of social connection. With less drinking has come significantly less partying: The share of young people who say they attend or host social gatherings declined by about 70 percent in the last 20 years.

America’s fitness boom, for example, has also mostly come from an increase in solo workouts—particularly for young men. Every gender and age group is more likely to work out alone than they were at the beginning of the 21st century, according to an analysis by Luke Pardue, policy director at the Aspen Institute’s Economic Strategy Group. The share of men under 25 who say they exercise by themselves has increased 60 percent in the last two decades—more than any other group. Similarly, Americans eat out more than ever, but the share of Americans who say they have all their meals alone has increased 50 percent in the last 20 years.

Back to Spishak. He is not just a pornosexual, which is self-explanatory. He is also a “gooner,” which requires a definition. As the journalist Kolitz wrote in his chilling and spectacular essay in Harper’s Magazine, gooning is a ”new kind of masturbation” that has gained popularity among young men around the world. Its practitioners spend hours or days at a time “repeatedly bringing [themselves] to the point of climax … to reach the goonstate’: a supposed zone of total ego death or bliss that some liken to advanced meditation.”

What hardly requires elaboration is that these young male gooners—and they do seem to be mostly men—are ecstatically alone. “This is a bunch of guys sitting alone in their rooms being viciously abused by their computers, sinking deeper into the despair that compelled them to seek out that abuse in the first place,” Kolitz writes. As they tumble into goonerdom, their relationships with warm-blooded bodies melt away. A porn producer admits to Kolitz that “we’re pushing people who are forgoing personal relationships because they’re so lost in their gooning addictions.” He continues: “Do I ever have questions of morality about that in my own mind? Yeah, I do. But has it stopped me? [Laughs.] No. I enjoy my job.”

Blessedly, the gooner seems to be a rare species of dude. But he represents the bleeding edge of a mainstream phenomenon, which is a culture that prizes solitude and an economy that warps itself around that revealed preference for aloneness.

You might suspect that the phenomenon I am talking about here is the infamous “male loneliness crisis.” In fact, I object to the term. Loneliness, the NYU sociologist Eric Klinenberg told me, is a healthy instinct: “that cue is the thing that pushes you off the couch and into face-to-face interaction.” A gambling addict who sits in front of a slot machine until the small hours of the morning and forgets the passage of time is experiencing neither loneliness nor the active desire to be around other people. What he is principally feeling, I’d suspect, is more akin to a neurochemical rollercoaster ride so arousing that he forgets other people exist to be missed.

While I know that some men are lonely, I do not think that what afflicts America’s young today can be properly called a loneliness crisis. It seems more to me like an absence-of-loneliness crisis. It is a being-consantly-alone-and-not-even-thinking-that’s-a-problem crisis. Americans—and young men, especially—are choosing to spend historic gobs of time by themselves without feeling the internal cue to go be with other people, because it has simply gotten too pleasurable to exist without them.

Several years ago, the philosopher Andrew Taggart coined the term “secular monks” to describe young men who associate solitude with strength. When porn seems less fraught than sexual partners, and when late night parties seem lower status than early-morning Pilates, a toxic asceticism is spreading throughout American life. No, the problem is not loneliness. The problem is that we’ve forgotten how to feel lonely in the first place.

III. The American Casino

Since Freud, psychologists have distinguished between theories of autoplastic and alloplastic change. With autoplastic change, the problem is the patient, and the patient must first improve himself. With alloplastic adaptation, the problem is the environment, and the subject should change his surroundings. There is a tendency in some corners of commentary to treat the problems of young men as mostly autoplastic: Dudes, get a grip! But I’d prefer, for the purpose of this essay, to play the alloplastic card. I want to consider the environment in which young men are monkifying themselves.

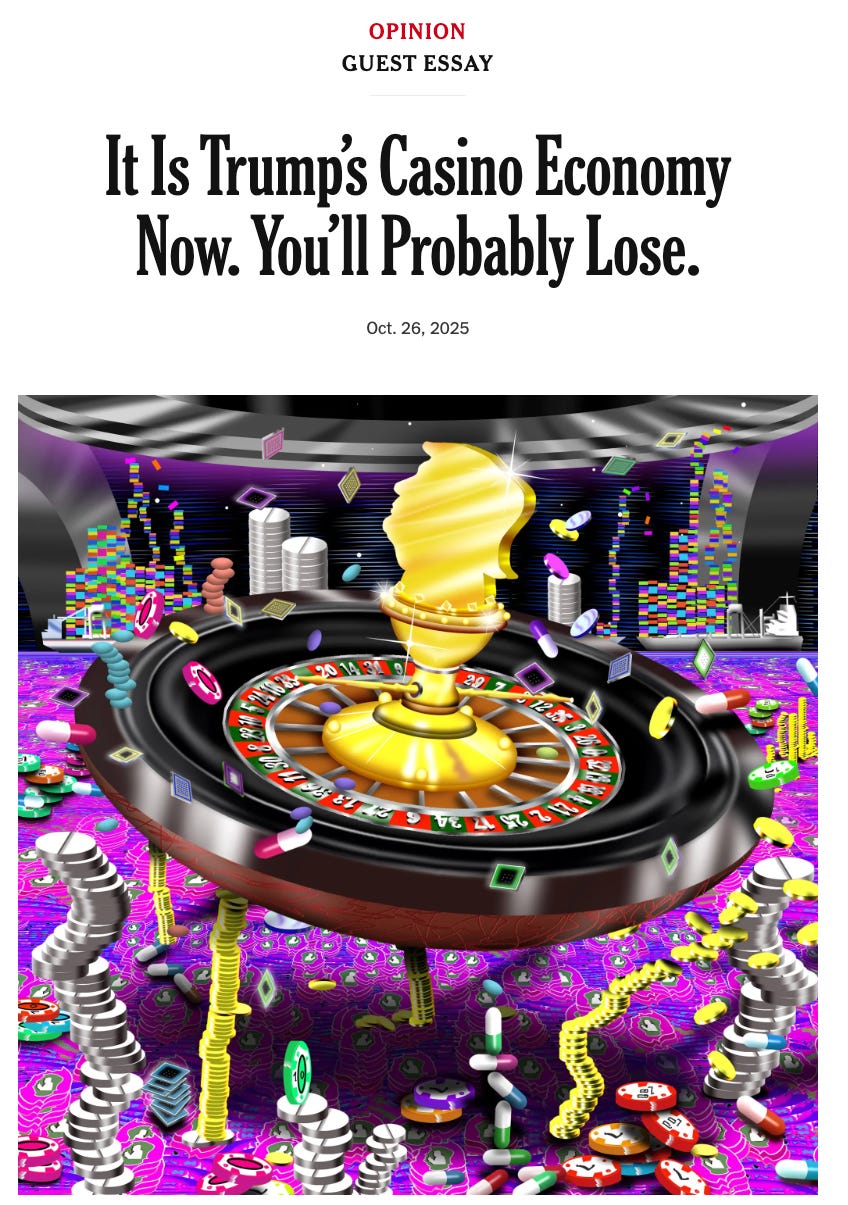

In the last few weeks, some of my favorite economic commentators, including Greg Ip and Kyla Scanlon, have suggested that the US economy is evolving toward what the author Hans-Werner Sinn once called “casino capitalism.”

To see how the US economy is becoming more like a casino, let’s consider another recent revelation from the American underworld. Last month, an FBI investigation into gambling led to the arrest of several prominent basketball stars. A former player was accused to leaking updates about LeBron James’s injuries to co-conspirators; a player was accused of taking himself out of a game to help a betting partner; and Portland Trail Blazers head coach Chauncey Billups was accused of telling gamblers that his team planned to lose a game.

As with gooning, we cannot say these scandals showcase a mainstream phenomenon. Still, they represent the sharpest edge of a general trend, which is the rise of sports betting, online gambling, and financial speculation, especially among young men.

Roughly half of men between the ages of 18-49 have a sports betting account. In New Jersey, nearly one in five men aged 18-24 is on the spectrum of having a gambling problem, according to the author Jonathan Cohen. America’s gambling compulsion extends far beyond sports, Cohen wrote in a New York Times op-ed with Isaac Rose-Berman:

If it feels as if gambling is everywhere, that’s because it is. But today’s gamblers aren’t just retirees at poker tables. They’re young men on smartphones. And thanks to a series of quasi-legal innovations by the online wagering industry, Americans can now bet on virtually anything from their investment accounts.

“We talk a lot about the ‘male loneliness crisis’ but in my estimation we don’t talk enough about the ‘male suckerfication crisis,’” Max Read wrote. Young men are “continuously cultivated” by their media to become dupes and suckers “in service of the profits of an ever-expanding roster of gambling and gambling-adjacent industries In the 2010s, the professional sports leagues saw that transforming themselves into legal gambling platforms would be a quadruple-win: They would get more viewers, more ads, more business partnerships, and more overall revenue. Like an unstoppable virus, this logic is infecting more and more industries. Stock trading apps, such as Robinhood, are pushing into sports betting. The operator of the New York Stock Exchange recently invested $2 billion in Polymarket, a platform for gambling on politics, sports, and anything else. Google is partnering with Polymarket to display betting prices in their search results. And why stop there? Put a scrolling chyron on the Facebook newsfeed to display betting options. Plaster TikTok with celebrity breakup parlays. Try a branded segment on Fox News: Welcome back to our expert roundtable, I’m Veronica, and the elimination of the filibuster are up to 15 percent today, according to our partners at Polymarket, and Mike, turning to you, is this a buying opportunity for viewers?

“Betting on football and elections is becoming as much a part of our lives as watching football and voting,” wrote Greg Ip at the Wall Street Journal. Just think about that for a moment. If everything is becoming television, and everything on television is trying to become gambling, then the end point is not hard to see: On every screen, a casino.

How did it come to this? One story is about law and policy. The Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association struck down a federal ban on sports betting. The Trump administration has been determined to loosen rules to permit more financial speculation in crypto currency, gambling, and beyond. “We are in the grip of a sweeping new age of financialization and innovation — the boldest transformation in money and investing since the 1920s — that is also driven by the idea of expanding access to markets,” Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote in the New York Times Magazine.

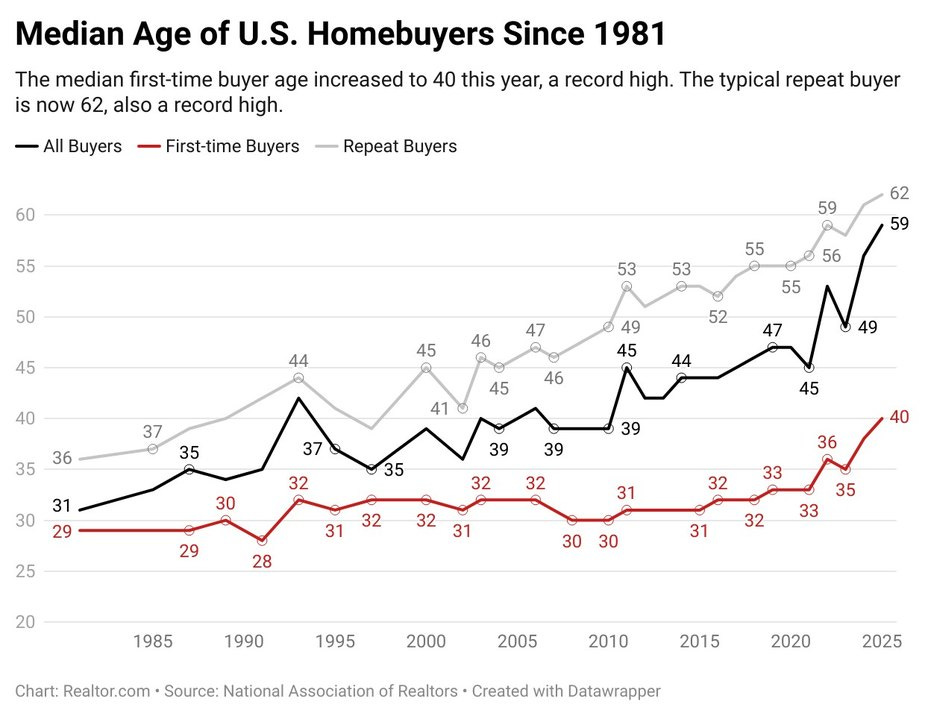

But it’s not just that betting is getting easier; it’s that living is getting harder. Young people are shut out of traditional wealth-building strategies, such as homeownership. The average age of first-time home buyers recently hit a modern record of 40. Just as poor people buy lotto tickets when they feel their income is “low relative to an implicit standard,” perhaps young people today are drawn to get-rich-faster schemes precisely because middle-class hallmarks, such as homeownership and children, feel like luxuries that require the sort of unlikely windfalls that only come from risky speculation.

The pro-social script—date around, marry, settle down, buy a house, have a kid—feels more like a luxury every year. The anti-social script—porn, posting, parlays—feels easy and even costless. If young people are throwing out the old script, it’s because they’re hunting for a deal, just like everybody else.

IV. The Shadows of Others

The sociologist Max Weber proposed that Christian asceticism gave birth to capitalism. Today it is capitalism that is birthing a wretched asceticism, as the casino economy turns our young people monastic. The monks at the casino represent an inversion of that old Christian principle. Whereas the Protestants that Weber studied were socially giving and financially stingy—their financial prudence created savings that could be invested in new enterprises—today’s monks are risk-averse in the world of bodies and risk-chasing in the world of bets.

This inversion of risk doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s the predictable result of how public policy and technological change have allocated risk and reward. Since the 1970s, America has over-regulated the physical world and under-regulated the digital space. To open a daycare, build an apartment, or start a factory requires lawyers, permits, and years of compliance. To open a casino app or launch a speculative token requires a credit card and a few clicks. We made it hard to build physical-world communities and easy to build online casinos. The state that once poured concrete for public parks now licenses gambling platforms. The country that regulates a lemonade stand will let an 18-year-old day-trade options on his phone.

In short: The first half of the twentieth century was about mastering the physical world, the first half of the twenty-first has been about escaping it.

This shift has moral as well as economic consequences. When a society pushes its citizens to take only financial risks, it hollows out the virtues that once made collective life possible: trust, curiosity, generosity, forgiveness. If you want two people who disagree to actually talk to each other, you build them a space to talk. If you want them to hate each other, you give them a phone.

It is a rotten game that we’ve signed up to play together, and somewhere deep down, beneath the whirl of dopamine that traps us in dark places, I think we know that a better game exists. Porn may be compulsive, and gambling may be a blast, but I refuse to believe that blasting ourselves with compulsion is the end state of human progress. The alternative is staring us in the face, and like most true things, it is obvious but not simple. The game is being alive. It comes with tears and boredom and disappointments and deep, deep joy. It is meant to be played in the sun and in the shadows cast by other people.

Beautiful column, Derek. It puts the “male loneliness” meme into a larger economic and social perspective. It makes me grateful that my own son, despite his youthful obsession with computers and my lax oversight of his online game playing, took it upon himself to occasionally get up from his desk and go outside to find a pick-up game of soccer somewhere. But this was in the 1990s, before iPhones arrived to steal everyone’s attention.

As compelling and shiny new technology is, we desperately need to put the focus back on human beings. Will we find leaders with the strength to do it? Will we find the strength within ourselves?

Devastating. I worry that a near future with AI-related labor losses will feed a meaningful segment of newly laid off workers into the pits of these isolating addictions, especially sports gambling (since that is so financially devastating).

I hope that the Democrats will start making a more explicit statement of concern about this and push to turn back public policy legalizing rampant gambling. The net effect seems to be serious dislocation of young people (men usually) from productive society, which is devastating for our whole economic system but especially on our productive capacity and our retirement system. Anger and resentment against our policymakers sleepwalking into a casino seem poised to be potent political issues.

While social conservatives (thinking of Deneen) have warned of this kind of predation of morally unmoored individuals by morally savage corporations, it seems unlikely that Republicans will serve at the frontline against the harms these companies cause.