The 25 Most Interesting Ideas I've Found in 2025 (So Far)

Charts and history lessons—across culture, politics, AI, economics, health, science, and the long story of progress

When I’m reading on my phone, I take a screenshot of whatever interests me. After a few months, I’ll have dozens to hundreds of morsels to serve as inspiration for essays and podcasts, including excerpts from books, photographs of magazine text, charts from economic papers, and screen grabs of tweets.

Before I had a newsletter, there was nowhere for me to publish this information inventory. Now that I have this newsletter, and I thought it might be fun and useful to organize the most interesting things I’ve seen this year by subject matter and write something about why they struck me and what story they tell about America or the world.

CULTURE

Marriage is rapidly becoming a high-quality luxury good.

Marriage is getting rarer, older, and more stable. Consider the typical 25-year old American woman. If she was born in 1940, she had an 80 percent chance of being married. If born in the 1990, she had a ~20 percent chance of being married. That’s an enormous shift in the typical life experience of American twentysomethings. As marriage has been both delayed and reduced as a social phenomenon, divorce rates have also declined significantly. First marriages that began in the 2010s are on track to have the lowest divorce rate since World War II.

One thing happening in the background here is that marriage rates are declining most among low-income and low-education groups. That means the marriages that do happen are more likely to involve higher-education, higher-income couples who have always had a lower divorce rate.

The young American religious revival is overrated.

There are a lot of news stories about Gen Z finding god, going to church, and generally leading America's religious revival. But how much of this trend is real? In an analysis of General Social Survey data, Ryan Burge finds that Gen Z is still the least likely to attend weekly religious services and the most likely to be so-called “never-attenders.” The second of the two graphs reproduced below compares Boomers (now in their 60s and above) with Zoomers (now in their 20s and below) and looks at their attendance rates between the ages of 18-29. When Boomers were young adults, just 15 percent of them never attended religious services. Among Zoomers today, it’s 38 percent.

Half of Americans don’t get their news from the news.

I don’t know how the Financial Times’ John Burn-Murdoch publishes so many interesting things every year. He’s like a warlock who’s mastered the dark art of interestingness, so you’ll see several of his graphics in this piece. I don’t think the following graph is surprising so much as it’s essential for people in the news industry (or people whose entire online schtick is blaming the news industry for every bad thing that happens) to remember: Half of Americans don’t get their news from print or online news organizations. They get it from social media, which means they follow influencers, or they let the newsfeed wash over them, or both. Traditional news organizations are still powerful, but they’re arguably less powerful than ever when it comes to shaping people’s attitudes toward current affairs.

The anti-social century is the anti-meaning century

Young people are spending less time socializing and less time partying than previous generations. What are they doing instead? Gaming alone, watching TV alone, scrolling on social media alone, and relaxing (often alone). None of that is particularly evil. But by their own testimony, Americans say these activities are significantly less meaningful than caring for children and socializing, both of which we’re doing less of. As a result, young adulthood today seems to be a tradeoff, in which the conveniences of entertainment-rich solitude are winning out over the meaningfulness of time spent with others.

Young people hate alcohol now … and it shows.

One of the more remarkable diet and health shifts of the last few years is the astonishing rise of young adults who say “drinking in moderation” is bad for their health. (I have a lot to say about that.)

Alcohol makes me less neurotic, more agreeable, and more extroverted. So perhaps it’s not totally surprising that young people today are more neurotic, less agreeable, and less extroverted than they used to be. Another Burn-Murdoch banger, of course.

Perhaps relatedly, young people aren’t having nearly as much sex as they used to.

Most notably, the share of young men between 22 and 34 who say they haven’t had sex in the last year doubled between the mid-2010s and 2022.

POLITICS

Was 1872 the most important year for political freedom in the world?

… Uh, maybe?! If we define political freedom as the ability to choose who governs us in a manner that’s protected from coercion or social pressure, 1872 belongs in the conversation.

In the essay "My Freedom, My Choice” about the book The Age of Choice by Sophia Rosenfield, author David A. Bell points out that for most of democracy’s history, voting was a performative and communal act, with public declarations and even open parades. The secret ballot that most Americans associate with the ballot box is a relatively recent invention, at least in modern Western history. In 1872, the town of Pontefract in West Yorkshire held an election for Parliament that took place by secret ballot. Bell writes:

Observers deemed the experiment a success, and within decades most of the Western world adopted this method of voting. Previously elections in the West had largely involved public meetings—often highly raucous ones—in which everyone could see how everyone else voted. Such settings made it difficult to conceive of the act as anything other than an expression of communal as opposed to individual preference.

But once voting became secret, it became far easier to imagine it as an expression of purely personal choice, in accordance with an individual's deepest beliefs and values. Another change encouraged this shift: the development of voting booths— tellingly known in French and German as "isolation spaces"—in which closed voters could, before marking their ballots, commune solemnly with their con-sciences.

The U.S. only began to adopt the secret ballot a decade later. But by World War I, the secret ballot was nearly universal in Western democracies. Imagine what people would say if the White House said it was banning secret ballots and forcing all voting to be public and thus open to state coercion, and you get a sense of why 1872 can be plausibly considered a formative moment in political freedom.

Trump turned white American politics upside down.

The graph below charts white Americans’ propensity to vote for each party based on their income decile. Between the end of World War II and the 1990s, rich white Americans largely voted for Republicans and poor white Americans typically voted for Democrats. In many years—1976, 1980, 1984, 1992, 1996, 2008—the relationship was practically linear, suggesting that every additional $10,000 in earned income correlated with an increased likelihood of voting for the Republican. But the Trump era has completely reversed the trend, and now it’s the poorest white Americans who are the most Republican while the richest white Americans are the most Democratic. As you can see, this is arguably the most dramatic inversion in the white electorate in modern history.

HOUSING

The South builds more houses

Here is a graph of housing units permitted per 1,000 residents per year in the U.S. (Sorry for the small font.) What you’re seeing is that southern states like South Carolina, Florida, Texas, Tennessee, and Georgia have consistently built more houses per capita than coastal states like California, New York, and Massachusetts. Illinois’s home building record looks putrid, too. Noah Smith offered a punchy summary of this graph: Blue states don’t build. Red states do. And some bozos offered a theory for what might be uniquely hampering blue-state housing construction here.

Why is the English-speaking world so bad at building homes?

Now here’s a look at housing growth per capita in the last 10 years (along the X axis) versus total dwellings per capita (along the Y axis). A lot is going on here, so let’s start in the bottom right-hand corner. South Korea has added a ton of homes in the last decade but from a low base. Countries like Finland, France, and Portugal have done an admirable job adding homes and also have some of the highest levels of dwellings per capita in the OECD.

And then, there are the English speaking countries. The U.S., the UK, Canada, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand all suck at adding housing. I don’t have a good explanation for this. Maybe, hundreds of years ago, England nurtured an anti-royal legalist culture that pilgrims, criminals, religious-freedom folks, and expats took to the Americas and Australia, and centuries later, these countries have developed societies with strong legal rights to push back against physical-world construction projects. I would love to solve the mystery of “Why does the English speaking world build so few houses?”

Dense walkable neighborhoods can save (at least several months of) your life.

A 2025 study followed 2 million smartphone users and traced the ones who relocated within the U.S. This natural experiment allowed researchers to learn whether people got more exercise when they moved to denser and more walkable cities. From the paper:

We find that increases (decreases) in walkability are associated with significant increases (decreases) in physical activity after relocation. For example, moving from a less walkable (25th percentile) city to a more walkable city (75th percentile) increased walking by 1,100 daily steps, on average ...

When exposed to the built environment of New York City after relocating, these participants increased their physical activity by 1,400 steps

In their conclusion, the authors find that large increases in walkability were associated with an increase in moderate to vigorous exercise of “about 1 hour per week.” Under the theory that every minute of moderate to vigorous exercise extends your life by five minutes, every week spent in a walkable city extends your life by five hours, every month adds 21 hours, every year adds 10 days, and every decade adds about 3 months of extra life.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

AI is eating tech employment,

From Mary Meeker’s AI report: If you subtract AI jobs from the IT industry, employment in US tech has been flat or declining for several years. The entire employment growth in tech is happening in AI.

13. AI is eating American infrastructure spending

The biggest tech companies are currently spending more money to power the AI boom than practically any group of companies has ever spent on anything. This is certainly true in nominal dollars, and it’s almost kind of true in inflation-adjusted terms. As I wrote in my recent AI rundown:

In the last six months, the four companies investing the most in artificial intelligence—Meta, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon—spent between $100 billion and $200 billion on chips, data centers, and the like … This is either the biggest tech-infrastructure project since the 1960s (since the beginning of the computer age) or the 1880s (the heyday of the railroad age). In January, JP Morgan’s Michael Cembalest calculated that the leading AI chip manufacturer Nvidia is on pace to capture the highest share of market-wide capital spending since IBM’s peak revenues in 1969. Not to be outdone, the economic writer Paul Kedrosky has calculated that AI capital expenditures as a share of GDP have already exceeded the dot-com boom and are now approaching levels not seen since the railroad build-out of the Gilded Age.

AI is eating the stock market, too.

The ten best performing stocks in the S&P 500, which are mostly tech companies associated with the AI capex boom, have so dominated net income growth in the last six years that it’s becoming much more useful to think about “The S&P 10 vs an S&P 490” than a traditional S&P 500 index.

Everybody’s using AI.

Technology used to proliferate slowly through the economy, especially when it required different actors to coordinate. The telephone was patented in 1876. But early on, it didn’t seem to have much use for Americans, who weren’t used to having something to tell their friends and family hundreds of miles on a frequent basis. By the early 1900s, there were fewer than 3 telephones per 100 Americans. The first year that more than half of US households had a telephone was 1946. Television, by contrast, went from 1 percent penetration in the mid-1940s to 75 percent penetration by the early 1950s.

AI is more like television than telephone, although it’s a little bit of both. It’s a technology that doesn’t require the simultaneous participation of another human, but it synthesizes the phenomenological experience of talking to another human. You can ask AI to code for you at 6am, look up stats at 12pm, and talk through your psychological dilemma at 11pm. Nearly two-thirds of Americans say they interact with AI at least “several times a week”; among Americans under 30, it’s three-quarters.

Self-driving cars are happening. (And that’s good.)

In 2015, I kept hearing that self-driving cars were going to take over the roads in 2020. That didn’t happen. Even by 2022, autonomous vehicles seemed like they might be a classic case of technologists over-promising a future that never arrived. (Jetpacks, anyone?) But now driverless taxis, led by Waymo, are booming. California’s driverless taxis now transport passengers more than four million miles per month. In the last year, autonomous taxi usage has increased eightfold. Technology sometimes happens like this: First come the audacious promises, then the loud disappointment, then the quiet success, and then the world changes. It seems important to point out here that driverless cars appear to be at least an order of magnitude safer than human-driven cars, which means the shift to autonomy could, over time, save millions of lives around the world.

HUMAN INTELLIGENCE

The best reason to think AI won’t destroy white-collar work is Jevon’s paradox.

One way to think about AI's effect on workers is asking the question: Is artificial intelligence a tractor or a spreadsheet?

When we invented tractors, the population of horses on farms plummeted, because the tractor essentially automated everything that farmers needed from a horse. If you carried forward the frame that all technology is a tractor, you would have predicted that the invention of the spreadsheet would decimate the employment of accountants and other occupations that dealt with spreadsheets. Instead, the increased efficiency of spreadsheet work turned basically the entire white-collar economy into a bunch of spreadsheet jobs, and the number of accounting, tax prep, and bookkeeping jobs has increased steadily in the age of Excel.

Jevon's paradox is an economic theory that refers to the idea that increased efficiency leads to more consumption rather than less. In the 1800s, the UK increased the efficiency of coal-burning factories. Did the burn the same amount of coal more cheaply? No, they burned more coal. In the 2000s, the cost of producing and publishing video entertainment plummeted. Did we make the same number of videos but more cheaply? No, we made one trillion videos. So one plausible prediction about AI is not that it will replace workers but rather that the collapsing cost of using AI to generate ideas will turn everybody into insufferable influencers. Sorry, I mean knowledge workers!

Historically, automation doesn’t destroy work so much as it moves the value of human labor to other parts of the product life cycle.

One way to be smarter about anticipating the economic effects of technological change is to read how previous generations anticipated technological change and got things right or wrong.

In the middle of the 20th century, the automation of manufacturing was so compelling and frightening to Americans that books like Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano anticipated the possibility that super-intelligent machines would usher in a post-work dystopia. In 1956, Congress published a long paper anticipating the economic effects of robots in manufacturing firms entitled “Automation and Technological Change: Report of the Joint Committee on the Economic Report to the Congress.” In one section on the direct effect of automation, the authors wrote:

Following the principles and definition of automation already derived, the direct consequences of applying automation to a productive system can be classified as follows :

Many direct production jobs are abolished.

A smaller number of newer jobs requiring different, and mostly higher, skills are created. These new jobs include equipment maintenance and design, systems analysis, programing and engineering,

The requirements of some of the remaining jobs are raised. For example, the integration of several formerly separate processes and the enhanced value of the capital investment increase the need for comprehension and farsightedness on the part of management. Also, greatly decreased inventories and more rapid changeover times create tensions which require more alertness and stamina.

Production in aggregate and per man-hour is enormously increased.

The production of new and better goods of more standardized quality becomes possible. However, there may be a loss of variety. Many different models are possible from combining a few standardized processes in different ways but, as in automobiles, the final products are still likely to look pretty much all alike.

There is an increase in the quantity and accuracy of information and the speed with which it is obtained. Management can thus have a clearer picture of its overall operation and by knowing the consequences of alternative courses of action it can act more rationally.

In most cases a more efficient use is made of all of the components of production-labor, capital, natural resources, and management.

I would love to report that 1950s economists were a bunch of technocratic buffoons who had no idea what was coming but, that whole thing is … incredibly insightful? The idea that US manufacturing automation would directly replace some production jobs but also create more complex managerial occupations that require a facility with design and engineering, while the speed of business will require a different kind of stamina that is intellectual rather than physical, and also the automation of factories might lead to a loss of variety due to managers seeking efficiency seems quite spot-on to me.

I’m worried that AI is getting smarter at the same time that we’re getting dumber.

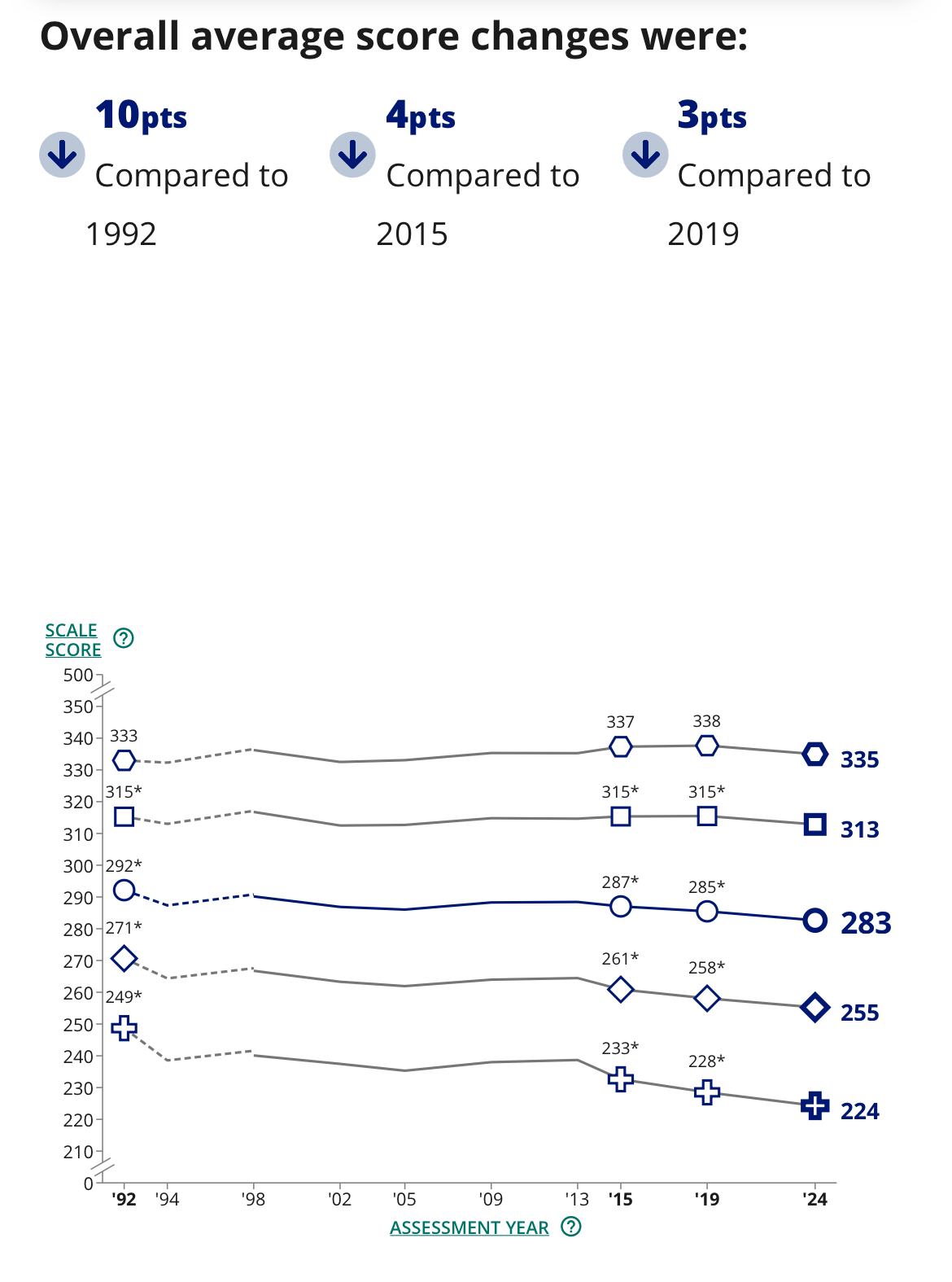

I'm basically an optimist, but I find it hard to argue against two claims. First, screens and social media make it easy to not pay attention in school. Second, generative AI makes it easy to cheat in school. I’m worried that the combination is going to wreak havoc on young people’s education. Add to that the fact that generative Al tools are going to get more intelligent over a period of time when teen and adult literacy scores are declining, and I think you've got the basic ingredients of a pretty serious cultural problem.

As for the data points: After decades of rising intelligence, teen and adult achievement scores are falling. Burn-Murdoch has called this phenomenon “peak human brain power.”

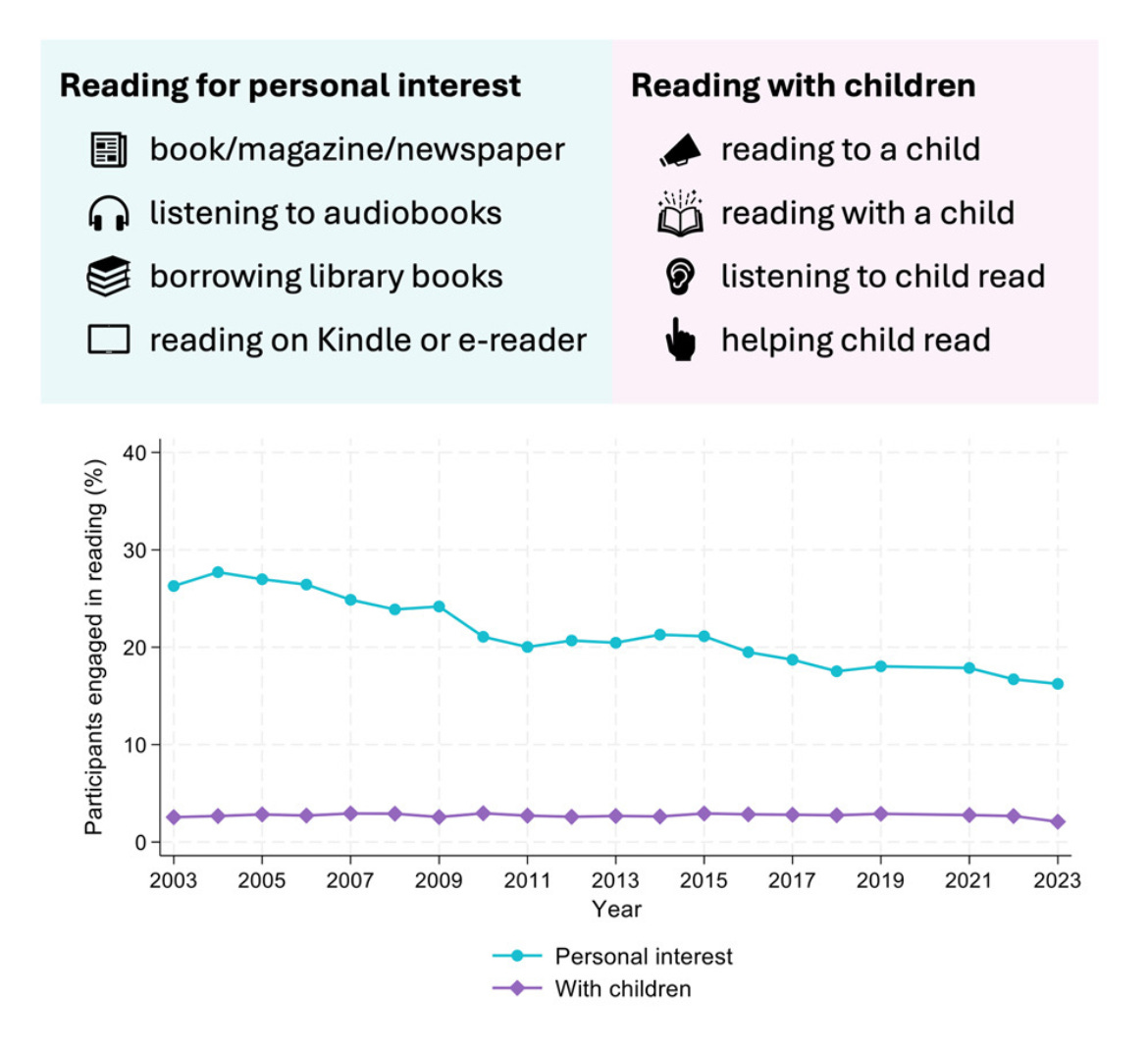

Meanwhile, an analysis of reading habits in the U.S. found “marked declines” in the share of people reading for pleasure daily, with decreases of 3 percent per year, especially among Black and low-income Americans.

And in the U.S., the nation’s report card from NAEP recently reported record-low average reading scores.

THE (NON-AI) ECONOMY

Re-industrialization just isn’t happening.

One argument for the Trump tariffs is that the U.S. tragically lost its manufacturing base in the last few decades, and we need a protectionist policy to revitalize American industry. The idea is that higher tariffs will pull more domestic and foreign investment into manufacturing, which will see a boom in employment that brings back the good ole days. It seems worth pointing out that, as Joey Politano shows in the graph below, US manufacturing is plunged in a worsening recession, with falling industrial output and declining employment. By this metric, the Trump tariffs aren’t just failing to achieve their objective. They’re gutting our non-AI manufacturing base.

It sure seems like there’s a lot of grift in the US economy right now.

Cullen Roche points out that the FTC tracks investment scams in their Sentinel report. There’s been a big increase in the last few years.

The richest 10 percent of Americans now account for roughly half of all US consumer spending.

Pretty self-explanatory. It’s interesting that most of the change in the last 36 years happened during the mid-1990s, which we think of as a pretty good economy for the middle class.

HEALTH

Vaccines work, and as confidence in vaccines declines, kids will get sicker (via Rachel Bedard, KFF data).

Confidence in vaccines has plummeted since COVID, a pandemic that ended when it did largely because of vaccines. The share of kindergarteners vaccinated against measles, polio, and whooping cough has declined meaningfully since 2021. In related news, measles outbreaks recently hit their highest levels of the century.

PROGRESS

Childhood bacterial illness and famine have been reduced so much that the greater global danger to children is obesity rather than starvation.

As recently as 1953, more than one in four people in India died before their fifth birthday. Now it's one in 30. Countries like India and Ghana saw child mortality improvements in about 50 years that took western European countries 150. Many of the drugs and medical interventions that have spread to India and Ghana were invented or discovered decades earlier. But progress is more about implementation than invention.

Progress is not the replacement of problems, however, but the replacement of one set of problems with a better set of problems. Today’s children are much less likely to die of starvation. But in an environment of caloric abundance, they are much more likely to be obese. In 2025, more children worldwide are living with obesity than are underweight. That's never happened before.

The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better.

I really appreciate this type of post. It's what I used to try to 'manually' get out of reading a half dozen other Substacks and spending too much time on Twitter. A lot of these are little gems that enrich our understanding of larger themes (or are seeds for topics that get debated a bunch). Just the right amount of detail and contextualization. And fully agree on the world philosophy!

Love the last one. It’s the message in Hans Rosling’s Factfulness. We have made a ton of progress. We should celebrate that progress and acknowledge we can do better