What’s the Matter With Dallas?

If Texas is so good at building homes, why have housing prices surged in Big D?

Programming note: TSMP is off this weekend, but I promise this newsletter will be about science again, soon :) - d

“Something is happening in the housing market that really shouldn’t be.” That’s how The Atlantic staff writer Rogé Karma framed a mystery that’s been bugging me for several months.

Most people know that America’s affordability crisis started in coastal metros, such as San Francisco and Los Angeles. But in the last decade, the biggest increase in home prices hasn’t taken place on the coasts. It’s happened instead “in the exact places that have long served as a refuge for Americans fed up with the spiraling cost of living,” Karma writes. Between 2014 and 2024, the median home price increased by 134 percent in Phoenix and 129 percent in Atlanta. In Texas, that bastion of building, the median home price increased by 99 percent in Dallas and 96 percent in Austin—both around the national average.

If Dallas is so good at building houses, why did its home prices double just like everywhere else? And why, in the last few years in particular, have home prices surged to the point that middle-class families struggle to buy their first home? It’s a good question.

One possible answer comes from the antitrust left, a group of lawyers, writers, and advocates who focus on the ways that big companies hurt America. They’ve argued that the consolidation of homebuilders in Dallas created a dangerous housing “oligopoly,” in which big companies now “undermine free and fair competition” by purposefully not building in order to juice their profits. When I called up sources in one prominent article to ask about the veracity of these claims, the sources didn’t produce any evidence, at all. In most cases they directly contradicted the antitrust story. The economist whose working paper provides an empirical model of oligopolistic homebuilding told me that he “100 percent” “would definitely agree” that Dallas is a bad example of harmful oligopoly.

But if Dallas’s high prices aren’t caused by greedy developers deforming the market, then where do they come from? I think I can offer a more complete story here. It’s about bad rules, big lots, hot demand, and a terrible pandemic—in that order.

The Dallas Story: NIMBY Goes South

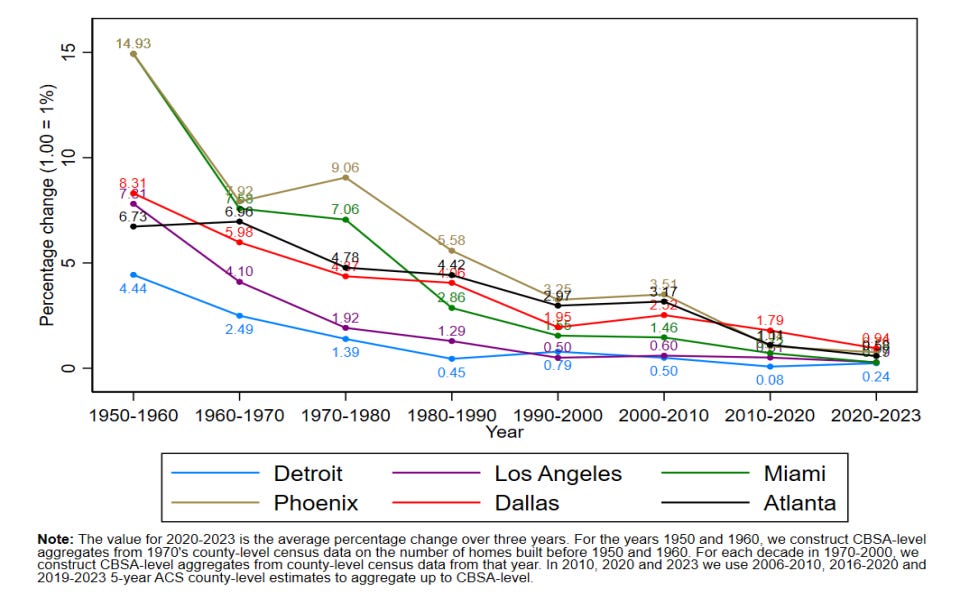

Since the middle of the 20th century, Dallas consistently built more homes per capita than the big coastal cities. Every year this century, it’s added more than twice as many homes per person as San Francisco. It’s important to state this clearly up top: Compared to the most dire markets for home construction, the Dallas metro is unambiguously a star.

In the last few decades, however, the star has dimmed. Rates of homebuilding steadily declined in Dallas after the 1960s, as they did in big cities throughout the south and west. As the economists Ed Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko explained in a 2025 paper, Sun Belt metros ran into different versions of the same problem: The more they built out, the more rules accumulated to slow their rates of building. In Dallas specifically, developers pushed outward into the hot suburbs and hotter exurbs. But over time, the burbs got crowded. To add more housing, Dallas couldn’t just build out. To keep up with demand, Dallas had to build up—or, at least, to add density by building on smaller plots of land. And something was getting in the way.

Over the years, restrictive rules and NIMBY attitudes bloomed throughout the Sun Belt just as both had sprouted decades earlier on the coasts. “As Sun Belt cities have become more affluent and highly educated, their residents have become more willing and able to use existing laws and regulations to block new development,” Karma writes. “Justin Webb, the owner of a small family-owned home-building business in Dallas, told me that when he started out in 1990, the local environment was ‘every builder’s dream.’ Not anymore. ‘Now everything is a negotiation; everything is a process.’”

John McManus, the editor in chief of the real estate site The Builder’s Daily, told me that as Dallas homebuilding pushed out into the far plains, “land use constraints have become more meaningful because the new parcels that have come online are subject to stiffer restraints.” In particular, McManus told me, Dallas homebuilders are struggling to build smaller, cheaper homes because of a set of regulations known as minimum lot sizes.

Whenever I mention minimum lot sizes to people who aren’t hopeless housing nerds, their eyes go milky grey and their hand moves slowly, as if summoned by hypnosis, toward the smartphone for an escape. So let me be quick and blunt: Minimum lot sizes are a skeleton key in housing policy. Large minimum lot sizes make density nearly impossible, because every new house is required by law to be situated on some enormous plot of land. The housing researcher Ed Pinto has said that if the first rule of real estate is “location, location, location,” the first rule of housing affordability should be “small lots, small lots, small lots.” If you want lower prices, you should want smaller lots.

The most common minimum lot size in the city of Dallas has until recently been 7,500 square feet. This has been a huge barrier to affordability. Among Dallas homes built since 2000, those on lots under 4,500 square feet cost a third less than those on larger lots, according to Salim Furth, a housing researcher at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. It’s very hard to build cheap housing if it’s illegal to build anything other than a single-family house situated on what is essentially a small ranch.

One might expect that efforts to reform minimum lot size rules would be easy-peasy in go-go Texas. One would be wrong. Texas NIMBYs now sound just like their California counterparts when you get them in a room with city councils, just with jauntier twang. At a recent local committee meeting to reform lot sizes in Dallas, one resident said allowing “duplex, triplex, fourplex housing units or accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods rings favorably only to developers.” Another told council members to “stop this blatant attempt to destroy our single-family neighborhoods.”

To be exquisitely clear: Dallas builds a lot of homes compared to the most housing-constrained cities in America. But it could do better. And the problems that were quietly festering in the Dallas housing market exploded during the COVID pandemic.

The Last Five Years

In 2020 and 2021, demand for new and larger homes in warmer climates exploded, fueled by low rates, cabin fever, and a booming work-from-home trend. People in colder parts of the country flocked to cities like Dallas and Tampa. Between the summers of 2020 and 2024, the Dallas metro area added more than 600,000 new people—roughly equal to the urban population of Las Vegas or Boston.

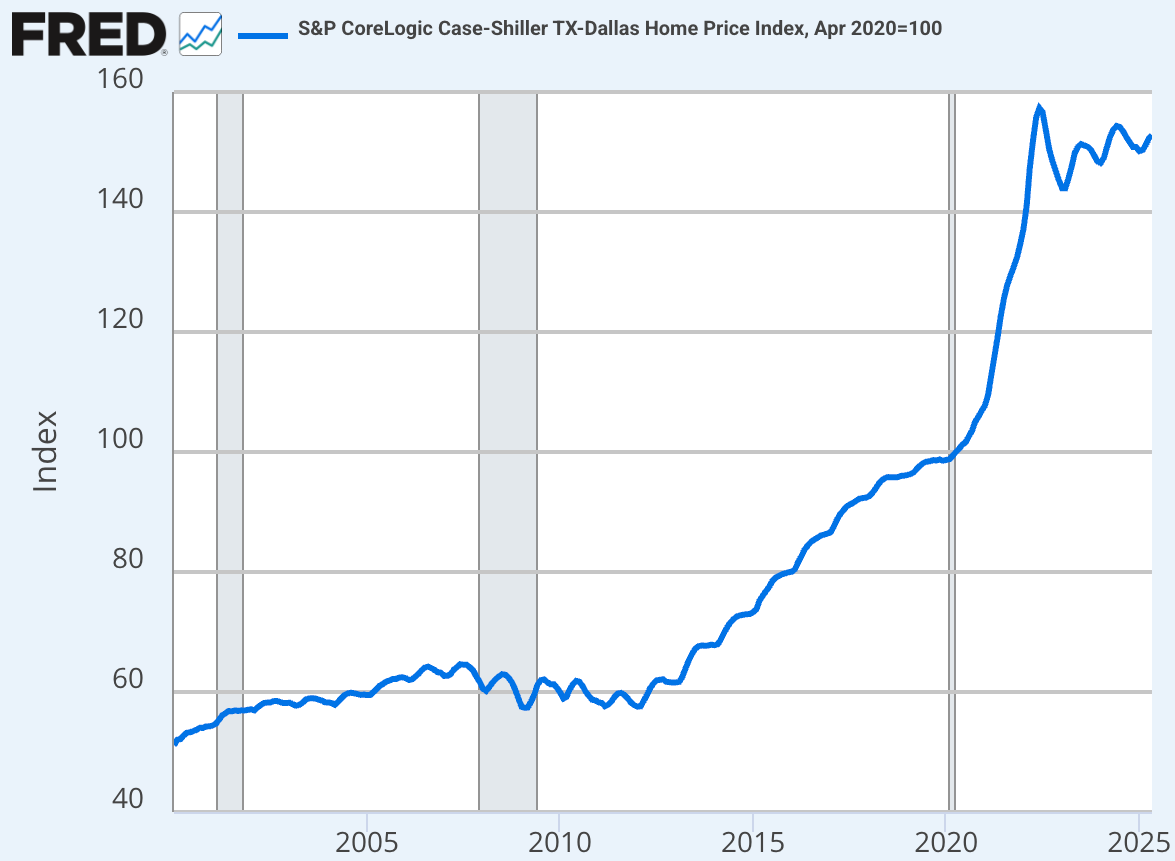

At first, Dallas builders struggled to meet white-hot demand. Materials got caught in supply chain snafus, and workers were scarce during the worst of the pandemic. “The Fed estimated that to meet additional demand” during the early pandemic years, “annual construction would have to triple,” the real estate analyst Lance Lambert told me. “That just wasn’t possible. There was only so much entitled land, labor, financing, and capacity.” As demand outran supply in Texas, prices exploded upward. The Case-Shiller home price index in Dallas surged by more than 50 percent in just two years.

But soon Dallas hit its stride. Housing starts in the metro reached a new high in 2022, before an interest rate shock made it difficult for some housing projects to pencil out. Price growth stabilized, as well, as you can see in the graph above. Between March 2022 and March 2025, Dallas home prices increased by just 0.88%—compared to 7.21% in New York and 6.5% in Chicago. In that period, the area’s total homeless population declined.

If I were serving as the defense attorney for Dallas metro housing production facing accusations that I’ve been overtaken by the forces of oligopolistic evil, I might make my opening statement something like this: As a population the size of urban Boston moved to Dallas between 2020 and 2024, our housing construction hit an all-time high, housing inflation declined, and the homeless population went down.

Antitrust folks have slagged on Dallas, calling it home to a dangerous oligopoly of builders. But the truth is that Dallas is like many other Sun Belt cities: a moderately flawed housing market, which has nonetheless managed to build a great deal of homes, where slightly better policies would allow them to build even more.

Lot Size Matters

This story has two codas.

First, Texas is acting on its minimum-lot-size problem. A new Texas law passed this year prohibits large cities from having lot-size minimums above 3,000 square feet in new subdivisions. Practically speaking, the law will allow developers to build smaller houses on smaller plots of land, which will likely be cheaper and more affordable for ordinary families and young homebuyers at a time when the average age of first-time homebuyers just hit a record high. It is a positive step forward, even if it’s not perfect. The law doesn’t affect lots in old subdivisions, which will still struggle to densify as more people move to Dallas.

Still, the law is progress. In the essay that launched many thousands of words, the antitrust lawyer Basel Musharbash suggested that we should “dislodge” the largest homebuilders in Texas, which would mean attacking the companies who are building the most. This would be foolish and counterproductive. It’s hard to imagine a worse policy for housing than taking down the most productive homebuilders for the sin of their scale. I prefer that Texas take on the homebuilding crisis by making it easier to build the kind of small affordable homes that Americans today desperately need. The city of Houston suggests that these reforms could make a big difference. Several decades ago, the city slashed its minimum lot size for urban single-family homes to 1,400 square feet, making it possible to replace one large house plot with several smaller homes. After Houston passed the law, thousands of townhouses were permitted. Today Houston’s Harris County has the dual honor of being the fastest growing county in America, with a 10-year housing inflation rate below the national average.

But the Dallas story ends in a surprising place. In the last year, home prices in Dallas actually declined. No, it’s not because all the homebuilder oligopolies suddenly found god. It’s because for all the problems in Dallas, the city really did build a great deal of homes. Supply rose to meet demand, and that’s kept price growth in check in the last three years. Meanwhile, throughout the northeast, home prices are still rising, in large part because restrictive rules and entrenched NIMBY attitudes have throttled supply growth in these places, while high interest rates have decimated the existing home market.

In housing, rules still rule. Where building is legal, building happens. Dallas can learn a lot from Houston. But the rest of America could still learn a helluva lot from Dallas.

Great analysis. A few quick additions from a DFW city planner:

1) Minimum lot sizes are a major issue. Yes, they drive up housing costs by requiring more land and encouraging larger homes. They also spread out infrastructure and service delivery, which increases long-term costs for both cities and homeowners. Similarly, on average lower-density development has lower valuations and therefore a smaller tax base to cover those costs. But the recent state law that overrides local rules only targets big cities—which aren’t building many subdivisions because they don't have a lot of vacant land for new single-family development. The real problem, unaddressed by the legislature, is low-density development in fast-growing exurbs like Anna, Melissa, Forney, Mansfield, and Celina.*

2) Pandemic-era price hikes weren’t just about supply. Demand surged from coastal buyers relocating to Texas. Someone selling a $1M home in LA can easily overpay in DFW, upgrade, or outbid locals thanks to their cash advantage.

3) Water is the biggest looming challenge. Many cities are hesitant to issue permits due to limited supply. The state is slow-walking new reservoir approvals while encouraging privatized transport of scarce aquifer water—raising major long-term concerns for growth.

4) Investors are skewing the market with cash offers and fast closings. It's hard to quantify the impact but the build-to-rent and private equity homebuying sectors are directly competing with, and therefore raising prices for, traditional homeowners.

*Sidebar here - the model is also shifting to put more costs directly on homeowners, with Municipal Utility Districts (MUDs), Municipal Management Districts (MMDs) and other financial vehicles beyond the traditional HOA that allows developers and cities to shift infrastructure costs off to buyers, who are then responsible for debt incurred to build their communities and the considerable maintenance costs that follow for roads, water, stormwater and other infrastructure. This is especially pervasive in the Houston area but is creeping to DFW's exurbs as well. The costs of owning a home, like insurance and traditional maintenance, will only be supercharged with the burden of these additional costs.

I attribute the problem to Big D energy.