The Anti-Abundance Critique on Housing Is Dead Wrong

Antitrust critics say that homebuilding monopolies are the real culprit of America’s housing woes. I looked into some of their claims. They don’t hold up.

The sharpest criticisms of the book Abundance have sometimes come from the antitrust movement. This group, mostly on the left, insists that the biggest problems in America typically come from monopolies and the corruption of big business.

In housing, for example, Ezra Klein and I write that a key bottleneck to homebuilding in the last few decades has been legal barriers to construction, including zoning laws and minimum lot sizes. This is a mainstream view supported by economists and scholars who have studied the issue for decades. The antitrust left, however, claims that the more significant factor is that big homebuilders abuse their power by holding back construction to juice their profits. “Big homebuilders withhold housing supply,” the antitrust advocate Matt Stoller has claimed. In their paper “Post-Neoliberal Housing Policy,” the law professors Christopher Serkin and Ganesh Sitaraman criticize market concentration in homebuilding and call for “tools from anti-monopoly policy.”

At a high level, I have never found these arguments persuasive. One hallmark of a monopolistic market is rising profits. But researchers have found that developer profits have remained steady. According to the National Association of Home Builders, profit margins as a share of overall home-sale prices actually declined slightly between 2002 and 2024.

Still, I wanted to spend more time engaging with the arguments of the antitrust housing folks. One of the most detailed articles in this space is an analysis of the Dallas, Texas, housing market by the lawyer and writer Basel Musharbash. In “Messing With Texas: How Big Homebuilders and Private Equity Made American Cities Unaffordable,” Musharbash writes that housing in the Dallas metro, like many other cities, has become much more expensive in the last few years. He also points out that homebuilders in Dallas, as in many other cities, have gotten bigger in the last few years. Musharbash claims that these things are connected: Large builders are crushing competition and restricting supply to sell houses at monopoly margins. To restore affordability, he says, policymakers should “dislodge the powerful corporations” that build America’s homes.

I’m not an economist or a lawyer. I’m just a journalist. To the extent that I’m good at anything, it’s calling people on the phone and writing down what they say. So I reached out to the primary sources that Musharbash quotes throughout the piece.

What I found was astonishing. The economist Musharbash cites told me that his theories had been misapplied. The housing analysts quoted in the piece told me Musharbash distorted their points and reached dubious, or even flatly wrong, conclusions. The leading monopoly researcher I spoke to, whose work has been celebrated by the antitrust left, told me that the entire thrust of the article—and, by extension, much of the antitrust-housing philosophy—defied sophisticated antitrust analysis.

The essay you’re reading is very long. But I can sum it up in one sentence: The Musharbash essay on Dallas—like too much of the antitrust left’s work on housing—is filled with out-of-context quotes, overconfident assertions lacking evidence, and generally misguided claims. Now let’s go through them one by one.

Claim #1: Dallas is a “homebuilder oligopoly.”

Reality: I called the key oligopoly researcher cited in the Musharbash essay. He disagreed with the use of his work and told me that any city with Dallas’s construction record was “100 percent” not an oligopoly.

It is a fact that home prices across the country have increased in the last decade. It is also a fact that homebuilders have gotten bigger in the last few years. The question at stake here is: Is the second fact causing the first fact?

I believe there is only one economic paper that unambiguously says yes.1 It is a 2023 working paper entitled “Fewer players, fewer homes: concentration and the new dynamics of housing supply” by the economist Luis Quintero. This research is load-bearing in the antitrust world. It’s quoted in articles and social media posts by the antitrust advocate Matt Stoller. You’ll find it in research from other antitrust scholars. And it seems to be the only empirical research in Musharbash’s essay.

I called Luis Quintero to ask what level of market concentration in homebuilding he considered to be dangerous. In the most concentrated markets, Quintero said, one or two firms account for 90 percent of new housing. But problems begin to accelerate, he said, if five or six firms account for 90 percent of new housing.

I immediately saw a problem. In Dallas, the top two firms built just 30 percent of new homes in 2023. The top six firms barely account for 50 percent of new housing. Musharbash's claim that a homebuilding oligopoly is crushing housing supply in Dallas relies on an economic analysis that doesn’t apply to Dallas at all. I asked Quintero about this: Would you agree that Dallas is “a bad application” of your paper? “I would definitely agree,” Quintero told me.

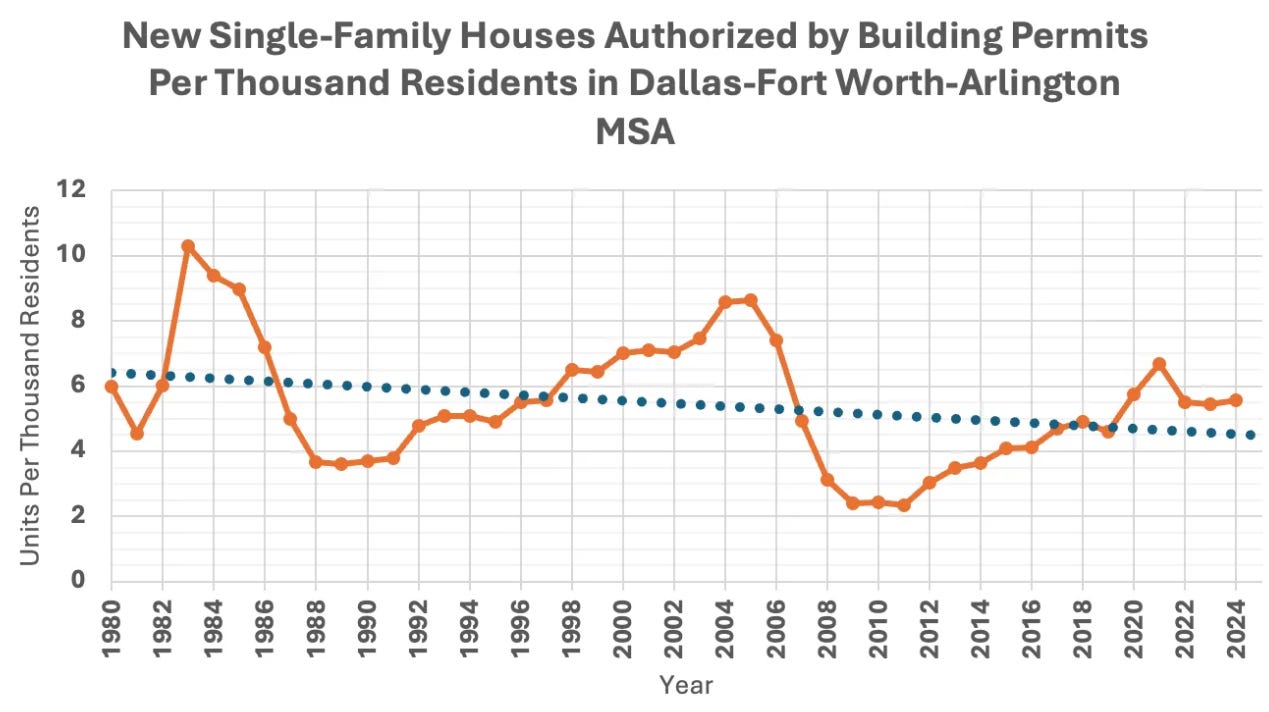

It gets worse. By Musharbash’s own calculation, the number of new single-family houses permitted per capita in the Dallas metro area rose steadily between 2010 and 2022. (This is illustrated in the graph below.) I mentioned to Quintero that steadily rising construction per capita in a fast-growing city seemed like a weird example of monopolistic abuse. “One hundred percent,” Quintero said. “I 100 percent agree that in places where construction per capita is increasing like that, it's very unlikely that [a dangerous level of] concentration is growing.”

So, Dallas doesn’t meet Quintero’s oligopoly threshold. Now let’s consider the rest of the country. I tracked down a complete listing of the country’s 50 largest homebuilding markets, from #1 Dallas to #50 Cincinnati. How many meet Quintero’s first oligopoly threshold (two companies = 90 percent of the market)? Zero out of 50. And how many meet his second threshold (six companies = 90 percent of the market)? One: Cincinnati. It turns out that the largest homebuilding markets just aren’t that concentrated, even when you accept the yardstick of the economist who’s offered the only empirical definition of market concentration in homebuilding that I can find.

To put it starkly: Musharbash’s essay relies on the work of an economist who told me his theory is being “100 percent” misapplied to Dallas; and the antitrust folks alleging a national homebuilding oligopoly are pointing to an economic definition of oligopoly that doesn’t apply to the 49 largest metros in the country.

Brief interlude: What does Luis Quintero’s working paper actually say, and are its findings plausible?

Quintero’s working paper plays such a foundational role in the antitrust housing landscape that I think it’s important to briefly address what it says and why I’m a bit skeptical of its findings.

Quintero looked at hundreds of markets along the East Coast between Virginia and New York between 2006 and 2015. He found that as dominant homebuilders increased their market share, new home production fell. “If you take two places with similar demand, and one place has fewer developers, that place is going to have less production per developer,” he said. From this study sample, Quintero calculated that the rise in market concentration in homebuilding is so severe that it has reduced the annual value of housing production nationwide by $106 billion a year.

After a long and polite conversation with Quintero on the phone, I came away with two concerns about his paper.

First, he uses 2006 as his baseline. This was a highly atypical year in housing. Just before the housing crash that triggered the Great Recession, May 2006 was the peak of 21st century construction employment. That very month was construction's single highest share of total employment since the postwar era. Using a bubble year as a baseline could easily throw off the overall findings of any economic analysis.

Second, as I told Quintero on the phone, I don’t think it’s plausible that oligopoly in homebuilding is destroying $100 billion in production every year if only one of the 50 largest homebuilding markets meets his red line of oligopoly. Quintero offered a defense of this discrepancy. He suggested that the most concentrated homebuilding markets tend to be either suburbs outside of major metros or small towns, since these are places “where new homes are a higher share of overall homes.” I can absolutely believe that. But I don’t see the value in discussing a “national” crisis in homebuilding oligopoly from which the 49 biggest metros are exempt.

Claim #2: Dallas housing experts say local homebuilders are monopolies who are “devouring” the market.

Reality: When I called up a Dallas housing expert cited several times in Musharbash’s essay, he disagreed profoundly with its thesis. He’s actually a big YIMBY.

Musharbash claims that Dallas homebuilders “undermine free and fair competition” by acting as monopolies. To make the case, he leans heavily on the work of John McManus, a housing analyst who is also the founder and editor-in-chief of the real estate site The Builder’s Daily. Musharbash writes:

“Described as “unstoppable, market-share-devouring juggernauts” by Builder’s Daily magazine [sic; should be The Builder’s Daily] these dominant incumbents appear to deploy their power to undermine free and fair competition …

Indeed, “[t]he scale and sway of market leaders” — particularly D.R. Horton and Lennar — means they “often monopolize access to trades and vendor resources” in local markets, constraining the ability of smaller builders to build at all, according to Builders Daily [sic, again]

I called McManus to ask if he really thought Dallas homebuilders were monopolies deforming the local housing market and driving up prices. “No,” he said. “I don’t think the price increases in Dallas have much to do with big companies at all. I’ve read that commentary, and I disagree with it. I don’t think the big builders have a strategy to sell fewer but more expensive homes.”

So, what did McManus think was more responsible for driving up the cost of housing in Dallas? “Land use regulation,” he said. “Zoning?” I asked. “Yes. Land constraints and zoning that require certain footage along the street, or minimum lot sizes, or requirements about three-car garages, are more the cause of the prices increasing now,” he said. “Municipalities have been adding more of [these rules] in the last few years, and land use constraints have become more meaningful because the new parcels that have come online are subject to stiffer restraints.” Beyond raising overall prices, McManus said, these rules specifically thwart the construction of starter homes, an issue that Stoller rightly bemoaned in a 2024 article. “Once you start to comply with these rules, costs rise and you can’t build something that’s accessible or attainable for a poorer household that doesn’t have a second earner.” By driving up the entry costs for homebuilding, these rules kill the market for starter homes.

In the Musharbash essay, The Builder’s Daily sounds like an anti-monopoly shop. But in our conversation, McManus sounded like a straight-up YIMBY. “I know some of my views reflect the narratives of the homebuilders,” he said. “But I know this industry deeply. I’ve read the work on zoning. I’ve done my research. I think it’s the zoning constraints that are in the way.”

I had one last question for McManus: What did he mean when he said big builders “monopolize” the market for craftsmen? “Oh, I didn’t mean that in a political way,” McManus chuckled. “I meant that big companies can offer more certainty for the trades. If you’re a plumbing or framing crew, and D.R. Horton can tell you, ‘we’ve got a 12-month job for you,’ you like that. You like to have that kind of certainty, because [even at lower rates] it guarantees a year of work.”

Claim #3: Industry experts have data proving that homebuilding oligopolies are holding back national housing construction.

Reality: I reached out to an industry expert whom the antitrust folks like to quote. He told me that he disagreed with the way that his analysis is being used by Musharbash, Stoller, and other antitrust advocates.

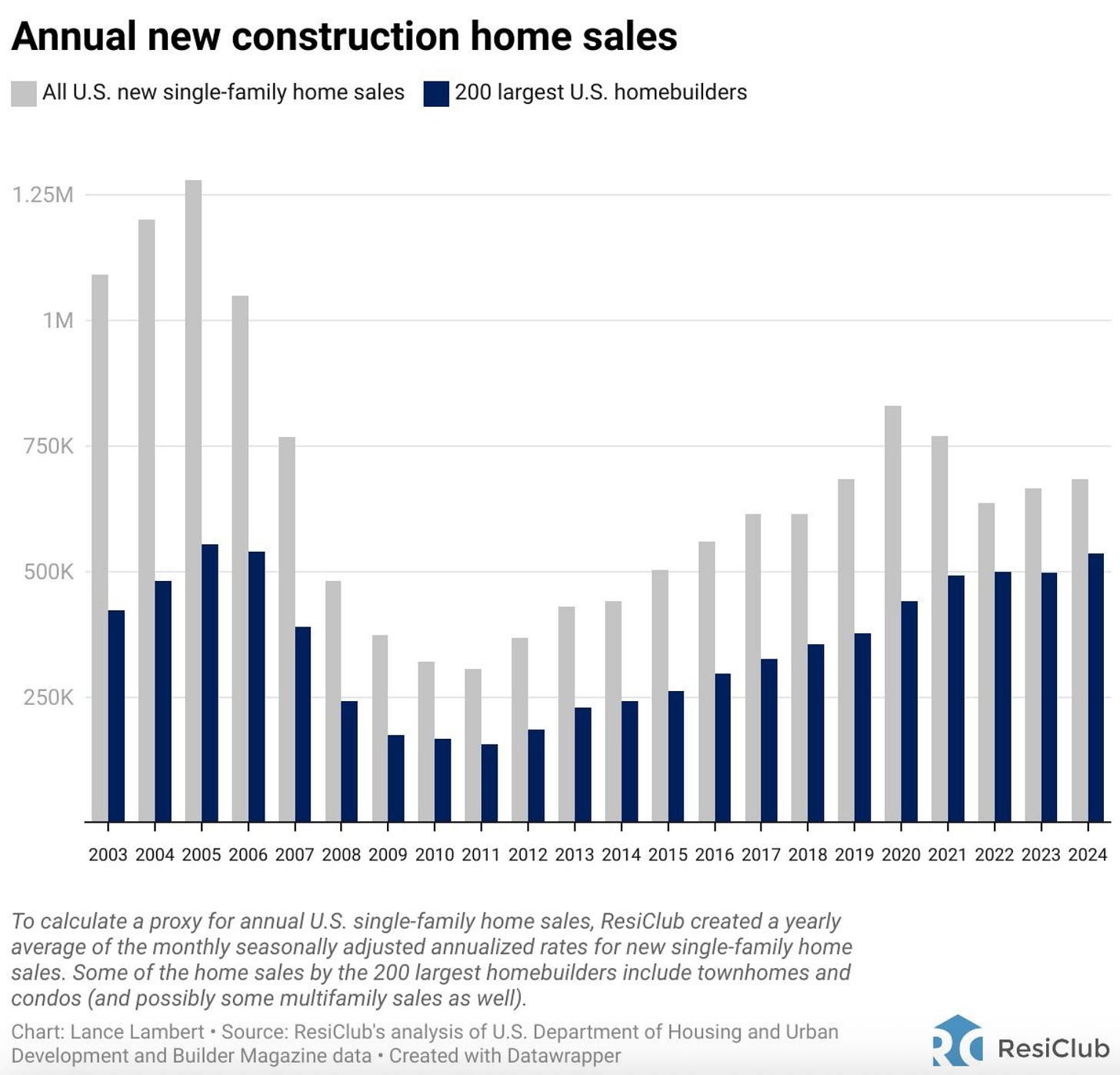

Another industry analyst the antitrust crowd often cites is Lance Lambert, the founder and editor of ResiClub. Lambert made the graph below showing that the largest homebuilders account for a rising share of national construction. Several antitrust folks have held up this chart as slam-dunk evidence that homebuilding monopolies are distorting the market and jacking up prices. Matt Stoller said this graph "really tells the story" of "how big homebuilders withhold housing supply.” In his essay, Musharbash makes the same claim when describing this chart: “As the percentage of total new home sales controlled by the top 200 homebuilders has increased over the past two decades, the total number of new home sales has declined by 25-50 percent.”

I know Lambert’s work, and I’ve always found him a hard-nosed analyst who’s neither a noisy YIMBY, nor a NIMBY, nor any other ‘IMBY. So I called him with a simple question. Did Lambert agree with the antitrust folks, who love to quote him so much, that the consolidation of big homebuilding companies was hurting housing supply?

“No,” Lambert said. “If you asked me what are the 20 biggest problems in housing in the last few years, I wouldn’t put market concentration in the top 20. It’s not something that comes up in my world of real estate analysis, at all. I could actually see the opposite argument from the monopoly guys, which is that larger homebuilders with easier access to capital” build more homes in the long run, thanks to the benefits of scale and large firms’ resiliency to market shocks. “It’s an observable fact that the big homebuilders build a ton of houses,” he said.

The antitrust people often point out that the Great Recession wiped out a lot of smaller homebuilders and left the bigger ones standing. Ironically, many of these folks now want to “dislodge” larger builders, to ensure that only small builders remain. Do we really want the construction industry to be exclusively populated by the sort of small, vulnerable builders who were wiped out in the last housing crisis? The antitrust crowd has an interpretation of history that seems to violate the clearest lesson of that history: Small companies can have downsides, and big companies can have benefits. A virtue of scale is that it can provide resilience in an age of crisis.

Claim #4: “X companies account for Y percent of this industry” is a smart way to think about market concentration.

Reality: A leading monopoly researcher told me this is an incomplete and overly simplistic way to think about monopoly power.

Musharbash, Stoller, and others rarely offer conclusive empirical evidence that large homebuilders are throttling the housing market for private gain. What they have instead are a lot of claims in the form of “[X number] of companies account for [Y percent] of homebuilding” in various cities. If that number is going up at the same time that other bad things are happening, readers are invited to assume that market concentration is the culprit.

This sort of monopoly math is so common that I wondered how useful it really was. So I reached out to James Roberts, the head of the economics department at Duke University. I think the antitrust folks will consider this a fair call. In 2019, Roberts co-authored a famous study uncovering evidence of monopoly power in the dialysis industry, which made such a splash in the antitrust space that Stoller himself called dialysis "the scariest monopoly I’ve ever found."

I wanted to know how a careful monopoly-hunter like Roberts would answer the question: If six firms account for 90 percent of a local industry, is that automatic proof of a monopoly? “No, it’s not,” Roberts said. “The statistic isn’t totally vacuous, but there’s basically no useful information about market power in that statistic alone.”

Alright, I said, if you were concerned about homebuilding monopolies, what questions would you ask? He offered this as his “non-ordered list.”

Does concentration clearly drive up the price of new homes? “I suppose it could theoretically, but keep in mind that new homes compete against existing homes that are resold,” which means a homebuilder in a big city is always competing on price against existing home sales, which ought to discipline the market. (If you’re selling your existing house in a market where D.R. Horton is building a new house, you are D.R. Horton’s pricing competition.)

Does concentration incentivize firms to build low-quality homes? “I find this unlikely for a similar reason,” Roberts said. If a homebuilding monopoly purposefully made crappy new homes, they’d be out-competed quickly by existing (and presumably non-crappy) homes on the market.

Can big companies hurt subcontractors by forcing them to accept lower prices? “Maybe, but if big homebuilders can offer trades longer guaranteed contracts”—as John McManus told me they often do—“you could see from the subcontractor’s perspective why it might be valuable to be able to negotiate with larger builders.”

Like Lambert, Roberts said he couldn’t rule out the possibility that larger homebuilders are actually good for the housing market— or even that today’s homebuilding markets would benefit from being even more concentrated. In industries with high capital expenditures, “economies of scale are beneficial to society so long as they’re not abused in specific ways,” he said. “You wouldn’t automatically want lots of firms in every industry. The bottom line is this is complicated, and it really depends on the details of the industry, not just simple statistics about market concentration.”

Vibes all the way down

Is it possible that homebuilding oligopolies are meaningfully constraining housing construction in some parts of America today? Yes. It’s a perfectly interesting question that deserves high-quality research vetted by high-quality experts. The literature on housing monopolies, however, is threadbare. It is hard to find a single study published in a single economic journal that plausibly claims that large homebuilders today are constraining housing supply. In lieu of careful findings, the space is filled with confident assertions.

A new pillar of the antitrust-housing literature is the 2025 paper "Post-Neoliberal Housing Policy." The authors, both law professors, describe "a new oligopoly” emerging in homebuilding today. If you look for a proof or citation for this claim—beyond an obligatory reference to the Quintero working paper—you’ll find a footnote that asks you to "see text accompanying note 261.” Note 261 cites a Matt Stoller essay entitled "It’s the Land, Stupid: How the Homebuilder Cartel Drives High Housing Prices.” I checked to see if that essay offered any empirical research or evidence that larger homebuilders led to higher housing prices, beyond the assertion that both things—homebuilders growing, prices rising—are happening at the same time. Other than yet another reference to the Quintero paper, it was hard to find. The closest thing was the screenshot of a headline of a 2017 Wall Street Journal article, entitled “Fewer Home Builders Means Happier Home Builders.” In the article, reporter Justin Lahart writes that “One reason behind optimism among housing construction companies is there is less competition among them, which has limited supply.” But there’s no evidence provided in the article for this latter claim. There’s no quote, no analysis, no citation, and not even a hyperlink to an external source; the whole article is less than 500 words long.

In sum, a paper with no new original research on this question relies on an antitrust essay with no empirical findings, which references a Wall Street Journal squib with no reporting to back up its claim. In too many cases, the antitrust-housing argument is an assertion, referencing an assertion, backed up by yet another assertion. Its vibes all the way down.

Real monopolies are dangerous. They can hurt consumers and patients. They can stymie competition and innovation. Twentieth-century antitrust remedies arguably unlocked both the film industry, with the end of the Edison Trust, and the software industry, with the AT&T consent decrees. You could plausibly argue that two of the most quintessentially American industry clusters—Hollywood and Silicon Valley—were made possible by anti-monopoly advocates. Antitrust is a proud American legacy.

Today’s anti-monopoly movement is good at finding monopolies where they exist. But they’re even better at finding monopolies where they don’t exist. The former is a mitzvah. The latter is a problem.

If doctors push a healthy patient into chemo, the damage is twofold. The patient is hurt, and the doctors lose credibility. I’m concerned the same is happening in the antitrust space. Dismantling today’s largest homebuilders on baseless grounds of market manipulation would almost certainly hurt homebuilding in the long-run. Accusing companies of being monopolistic with weak, circumstantial, and misinformed evidence will do nothing to build public or elite confidence in antitrust reform. Instead, a long record of false positives could muddy the case for remedy where it’s needed.

America deserves a better antitrust movement with better evidence. Musharbash’s essay quotes experts without talking to them. He cites papers without double-checking the findings. He digs up reports whose authors reject the conclusions. The whole thing looks like a lawyer who arrived in Dallas with a conviction in hand and shaped the evidence to fit the indictment.

In Abundance, we write that policy makers should think of themselves as detectives who investigate mysteries before they indict. If the antitrust left is going to convince me that I’m wrong about housing, I don’t need them to prove to me that they’re clever lawyers. I need them to show that they can be honest detectives.

***

Thanks for reading. Come back tomorrow for Part 2 of my analysis, where I’ll explain what really happened in Dallas and why I think unaffordability became a national phenomenon if the cause isn’t oligopolies.

Quintero himself told me that his paper was unique in the literature. But if commenters or academics can point to others, I’ll edit this sentence!

What's always been strange about this line of criticism is that restrictive zoning rules affect small homebuilders the most. Big homebuilders can afford expensive lawyers to fight re-zoning battles, they have the capital to buy and hold land while they wait for permits, and they are more likely to have political connections to smooth everything over. Loosening zoning rules would make it easier for small homebuilders to compete. Even if you think the problem with housing is monopoly (which Derek shows it isn't), you should still be against zoning because it helps concentrate power in the hands of bigger homebuilders.

Phenomenal piece, Derek.