What Caused the 'Baby Boom’? What Would It Take to Have Another?

Governments worldwide are trying to increase fertility with cash. But the most famous birthrate "boom" had a lot to do with science and technology, as well.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoy this article, last week’s essay on The Death of Partying in the U.S.A., or my feature story on The Anti-Social Century, consider becoming a subscriber to this newsletter to receive more essays on the social crises of our age.

In rich countries around the world, birth rates have fallen to historically low levels. Governments have responded with a confetti cannon of policy ideas to increase the number of babies, including parental leave plans, preschool programs, tax credits for parents, and even government-sponsored speed-dating events. To the extent that these programs have worked, their success has been mixed and, at best, moderate. Even a country like France, with its famously robust support for infants, still has a fertility rate significantly below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman.

So, what would it take to actually engineer a new baby boom in the U.S. and throughout the world?

The official baby boom—the period between the 1930s and 1960s when birth rates soared in the West—is so famous that its fame obscures its strangeness. Imagine being a journalist or demographer in 1925. For the previous 100 years, going back to the early 1800s, the fertility rate in the U.S. and practically every other rich country had steadily declined toward the replacement rate of 2.1.1 Nothing in the history of western family life or economics could have predicted what happened next.

In the 1930s and 1940s, fertility in the U.S. surged suddenly by more than 70 percent. It happened in cities and in rural areas; among working women and non-working women; among college graduates and couples who didn’t finish high school; among white and nonwhite couples; in the U.S., Europe, and beyond. In Birth Quake, the Barnard economist Diane J. Macunovich called the baby boom "a totally unexpected, earth-shattering, and ground-breaking event experienced not just in the United States, but in virtually the entire Western industrialized world."

The enigma of the baby boom is profound. It didn’t just reverse a century-long trend. It also unfolded during a period of “rising income, urbanization, [and] educational attainment … many of the factors that economists and demographers typically associate with declining fertility,” the economists Martha J. Bailey and William J. Collins wrote. Nearly a full century later, one of the most famous social phenomena of the last 100 years is still one of the most mysterious.

Was It … Expectations? Male Wages? Technology? Science? Housing Policy?

For a long time, my potted explanation for the baby boom was that Americans finished off World War II in such a glorious mood that the spirit of the age produced a brief storm of giddy horniness, resulting in a historic brood of infants. I’m currently reading Philip Roth’s novel American Pastoral, in which his alter-ego Nathan Zuckerman imagines a high-school reunion speech for the class of 1950, and it captures the vibe of the postwar years:

Everything was in motion. The lid was off. Americans were to start over again, en masse, everyone in it together. If that wasn't sufficiently inspiring—the miraculous conclusion of this towering event, the clock of history reset and a whole people's aims limited no longer by the past—there was the neighborhood, the communal determination that we, the children, should escape poverty, ignorance, disease, social injury and intimidation—escape, above all, insignificance. You must not come to nothing! Make something of yourselves!

In the 1960s, the economist Richard Easterlin came up with perhaps the most famous explanation for the baby boom, which rendered Roth’s prose as an economic theory. The Great Depression had demolished young Americans’ expectations of the future. As the postwar economy boomed, they found themselves thrust into a world of plenty—the lid was off, the clock of history reset—and they responded to the windfall by having bigger families. By this account, the unusual juxtaposition of a Great Depression and a greater postwar economy created the perfect conditions for a one-off boom in births.

The Easterlin Hypothesis sounds wise, and as we’ll see, it gets some things right. But it suffers from at least one glaring problem. The timing is off. Although demographers consider the year 1946 the official start of the baby boomer generation, the actual increase in fertility began about a decade earlier, in the 1930s, when unemployment was high and material expectations were low. What’s more, fertility in the U.S. peaked in 1960. It’s frankly implausible that 25-year-olds in the 1960s were having big families because of the lifetime earnings expectations they formed while learning about zippers, buttons, and moo-moo cow sounds in pre-K in the late 1930s. And yet, the Easterlin Hypothesis is still famous, in part because no other compelling theory has fully supplanted it.

For my money, the best story starts with science and technology. “Parenthood rapidly became much easier and safer between the 1930s and 1950s” thanks to changes in household technology, scientific advances in maternal health, and policies that reduced the cost of family formation, Anvar Sarygulov and Phoebe Arslanagic-Wakefield write in a wonderful review of the subject in the journal Works in Progress.

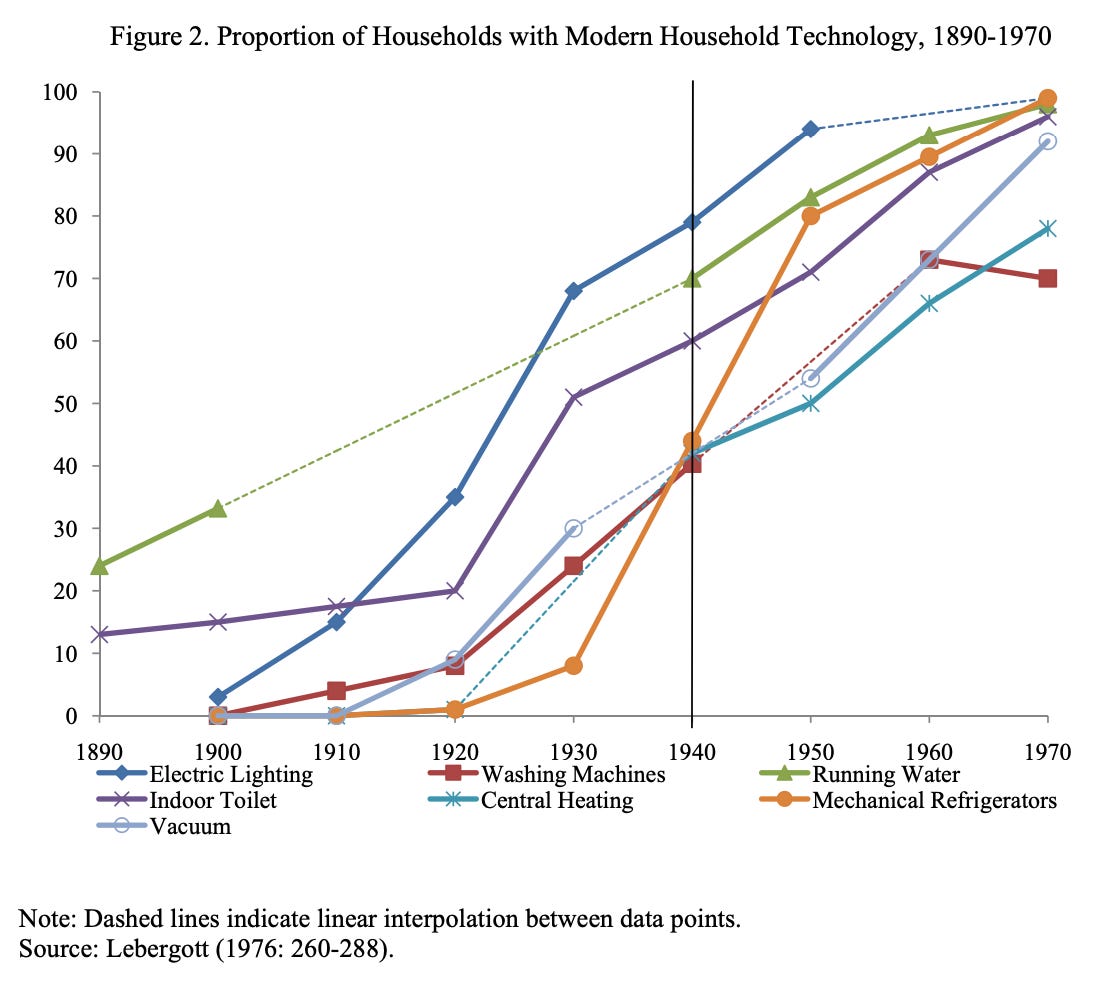

First, between the 1920s and 1950s, the modern home experienced a mini industrial revolution. The share of households with new electric appliances—such as refrigerators, stoves, vacuums, and washing machines—exploded upwards. The economists Jeremy Greenwood, Ananth Seshadri, and Guillaume Vandenbroucke argue that this "atypical burst of technological progress in the household sector" lowered the cost of having children, and this technological shock created a boom in fertility. As you can see in the graph below, this explanation is facially plausible, as the one-off surge in modern household technology took off in the 1930s, just as child births started to rise. Over time, however, the electrified household became commonplace, and the continuous rise in real wages increased the opportunity cost of having kids, so this one-time burst in fertility petered out.2

Second, between the mid-1930s and mid-1950s, the US maternal death rate fell by 94 percent, according to Sarygulov and Arslanagic-Wakefield. Early antibiotics in the 1930s, followed by the mass production of penicillin in the 1940s, “drove down incidences of sepsis, [which were] responsible for 40 percent of maternal deaths at the time, and made caesarean sections safer,” they write. The entire West saw huge declines in maternal mortality starting in the 1930s, which could explain why the baby boom wasn’t confined to the U.S. but extended across western and Northern Europe, Canada and Australia. Like the debut of electric refrigerators in kitchens, the reduction in maternal mortality was another event whose timing matches the moment of liftoff for the baby boom.

Third, a deliberate national policy to reduce the burden of homeownership may have also contributed to the surge in midcentury fertility. In their 2025 paper “Did the Modern Mortgage Set the Stage for the U.S. Baby Boom?”, economists Lisa J. Dettling and Melissa Schettini Kearney found that the introduction of low down payment, government-guaranteed mortgages in the 1930s and 1940s led to dramatically higher rates of home ownership among young couples. “Mortgage insurance programs led to 3 million additional births from 1935-1957, roughly 10 percent of the excess births in the baby boom,” the authors conclude. Lyman Stone, a researcher at the Institute for Family Studies, has told me that the relative affluence of young men has historically been a key predictor of high marriage rates. And, indeed, the combination of cheap housing and a strong postwar economy for working men contributed to a surge in mid-century matrimony. Between 1930 and 1960, marriage rates increased not only in the U.S., but also around the world, rising by more than 15 percentage points in Australia, England, Denmark, West Germany, Norway, and Sweden.

As new machines, better medicine, cheap homes, and rising incomes made parenthood easier, what started as a technological revolution evolved into a cultural movement, according to the gender and equality author Alice Evans.

Madison Avenue “raised the status of parenting” in the 1940s and 1950s, Evans told me, and “popular magazines extolled the virtues of domesticity.” Big families became a norm, an aspiration, and a social contagion. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, many young people were getting married early and having lots of children, not because they were so impressed by the labor-saving potential of new washing machines, but because they were genuflecting to the received wisdom of the age. One measure of the strength of this cultural norm was the potency of the backlash against it. When Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique in 1963, claiming that American mothers were bored out of their minds, she was naming and shaming the tacit assumption that “fulfillment as a woman had only one definition for American women after 1949—the housewife-mother."

Economists can’t measure peer effects and media influence as precisely as they can tally up national income. But just because something is not easily counted doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. The most careful researchers in the fertility space have consistently emphasized the importance of culture in the decline of fertility in the west. In their excellent new review of the literature, Kearney and Phillip B. Levine conclude that today’s falling fertility rates are not a pure economic phenomenon but rather a "broad reordering of adult priorities" toward personal fulfillment and career and away from early marriage and childrearing. I think they’re right. But, again, the greatest enigma is not why young couples today are extending a 200-year trajectory of falling or flatlining fertility, but rather why young people between the 1930s and early 1960s took this trajectory, lit it on fire, and briefly constructed a different family formation norm that deviated from the entire sweep of modern history.

Is Another Baby Boom Possible?

I think there is a disconnect between much of the fertility policy debate and the history of fertility in America. The frequent insistence that sufficient government spending can create a new baby boom exists in stark contrast with the historical fact that the midcentury baby boom was not a purely economic phenomenon3. It was a technological and scientific revolution, coinciding with an expansionary federal housing policy, climaxing during the deliriously bust-to-boom postwar years, all of which was transmitted through media and marketing into a social craze for bigger families. If there is such thing as a perfect storm in sociology, the baby boom was a perfect storm.

The question more people should be asking is: What are the technological and scientific breakthroughs that could create a new baby boom between 2025 and 2050, just as electrified household tech and antibiotics may have done between 1935 and 1955? One could imagine great leaps forward in IVF efficiency, or egg retrieval techniques, which would allow older women to have as many children as they want—and when they want. In her exceptional review of the frontier of fertility medicine, Ruxandra Teslo writes that one day in the coming decades, science might allow 40-year-old women to take any cell from her body—say, skin cells scraped off their forearm—and transform it into eggs that could be fertilized in vitro. She writes:

Cellular reprogramming allows us to modify a cell’s destiny. By adding a cocktail of four proteins to cells in a dish, researchers have been able to reverse a cell’s differentiation and obtain stem cells from mature, specialized cells. These artificially produced stem cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells, can now be differentiated into a whole range of desired cell types, allowing researchers to convert one type of mature cell into another.

The creation of actual eggs from such stem cells is a process known as in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, and it would allow older women to bypass the need for egg freezing entirely. Whether such a thing is feasible in our lifetimes is uncertain, both because the technology is complex and because women’s health and fertility receive very little basic research funding compared to categories like cancer and metabolic disorders. (The persistent underfunding of women’s health and fertility is a subject worthy of its long essay, but you should read Ruxandra to get started.)

Rather than end this essay in a place of surreality—growing babies out of reengineered skin cells?!—I’d like to ground us in reality. The decline of birth rates around the world is one of the most profound social phenomena of our age, in part because it seems to be among the least reversible. It’s appropriate to use government resources to reduce the cost of raising children: Rich advanced nations should support parenthood, because children are precious beyond their potential to become future dollar-generating cogs of the labor force. But any honest accounting of the baby boom should teach us that last century’s one great surge in births was as much about technology and science and their ability to shape culture, as it was about cold hard cash. If we took this history seriously, we might spend more money on not only parents of young children but also the basic scientific breakthroughs that would make it easier for future parents to have the children they want, whenever they want them.

While the fertility rate declined steadily throughout the 1800s, the mortality rate of children also decreased in that period. As a result, the net reproduction rate didn’t decline as sharply.

Honor demands that I inform you of this paper, which takes issue with the claim that household electrification led to the baby boom. One of the authors' most compelling points is that “the Amish, who used modern technologies much less than other US households, experienced a coincident baby boom.” I’m telling you, the baby boom was weird.

To me the biggest piece that is missing today is optimism. They were riding high on a wave of American exceptionalism and a belief in making a better world. Today's young people wake up every day with a sense of dread and uncertainty. If we want people to have kids they have to believe in the world and what it will become.

This tracks for me. We have three kids. Money played no part in our decision not to try for a fourth.

My wife stays at home. We have family nearby who help us out. We were fortunate to be able to hire help to clean and mow after our twins were born.

And yet, we still feel constantly overwhelmed.

If you could reduce the mental load of modern parenting, you might be onto something.