How Pickleball Explains American Culture

In 2019, pickleball was half as popular as badminton. Last year, it was more popular than baseball. What does its rise tell us about fads, fitness, and culture?

The aftermath of the pandemic has divided Americans into deeply oppositional camps. Some believe mRNA technology is a miracle, while others think it should be banned. Some believe the lab-leak hypothesis is plausible, while others find it condemnable. Some consider Operation Warp Speed one of the great public policy programs in American history, while others have rejected all of its lessons.1

And then there’s pickleball.

No sport has attracted more fans or more controversy since 2020 than this blend of tennis, ping-pong, paddleball, and badminton. The game is “driving everyone nuts,” causing “shattered nerves [and] sleepless nights” with the infamous pock-pock-pock sound of plastic hitting paddle. In Washington, D.C., where I live, the sport’s surging popularity has pitted neighbor against neighbor, created fights between tennis fans and the “pickleball lobby” (apparently a thing), and inspired the Washington Post to call it simply “the worst.” A manifesto titled "Against Pickleball" called on tennis players to “oppose the gangrenous spread of pickleball at every turn.”

I don’t know about gangrenous, but there is no debating the fact of its exponential growth. According to data I obtained from the Sports & Fitness Industry Association, pickleball isn’t just the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. It might be the fastest-growing sport in modern American history.

To give you some context for pickleball’s pre-pandemic popularity, think about badminton. And now think about something half as popular as badminton. That was pickleball in 2019. Total pickleball players in the U.S. were outnumbered by participants in archery, bow hunting, fly fishing, indoor climbing, snorkeling, and sledding. Now it’s more popular than all of those pastimes … and America’s pastime. Yes, more Americans played pickleball last year than baseball2.

From the SFIA report (my emphasis):

For the fourth consecutive year, pickleball is the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. In 2024, 19.8 million Americans participated in pickleball, a 45.8% increase from the 2023 figure and an incredible 311% increase from three years ago.

…

Racquet sports as a whole continued to be in a growth phase. Five out of seven racquet sports that SFIA tracks increased their year-over-year participation totals. Pickleball (45.8%) and tennis (8.0%) were both in the top 10 for the largest yearly participation increase.

As I read through the SFIA report, I wondered if pickleball wasn’t just the fastest-growing sport in America. Might it also be the fastest-growing sport in American history? And what does the faddish nature of sports tell us about American culture and American tastes, more broadly?

Racquetball was the pickleball of the 1970s

In 1980, Robert J. Halstenrud, a manager at A. C. Nielsen Company, presented a report on changes in sports participation in the 1970s. At the time, no activity in America was growing faster than racquetball. Between 1976 and 1979, racquetball participation "skyrocketed" from 2.8 million to 10.7 million, roughly matching the growth rate of pickleball in the early 2020s. Tennis grew even more in Halstenrud’s analysis. Between 1973 and 1979, total participation went from 20.2 million to 32.3 million.

So, pickleball isn’t the first time that a racket sport exploded in popularity in the U.S. In fact, I guess you could say pickleball isn’t even the first example of a racket sport surging in participation during a period of elevated inflation and plummeting trust in the executive branch.

There seems to be something about racket sports that’s particularly faddish, with Americans constantly switching back and forth between various ways of using a paddle or racket to whack a little orb. The racquetball bubble inflated fast and burst almost as quickly. After being the “it” sport of the 1970s, its total participation has fallen by about 70 percent in the last four decades. Meanwhile, table tennis soared in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s—in 1973, 33.5 million Americans said they played it—and then its popularity fell dramatically, with total participation down to about 15 million today. Tennis is the same story. In 1979, 32 million Americans said they played tennis, but in the 1980s and 1990s, tennis participation in the U.S. crashed by more than two-thirds, according to the National Sporting Goods Association's (NSGA) Sports Participation research study. But now, after another 20 years, tennis participation has more than doubled all over again.

Fitness is a fashion

Perhaps this is a good place to place a confession: Yes, I play pickleball. Kind of a lot, to be honest. To give you a sense of my social group’s pickleball-playing habits, consider that one friend requested that his bachelor party be a long weekend at an Airbnb with a pickleball court in the backyard, where we proceeded to play for at least five hours a day, for four consecutive days. By the end of the weekend, each member of the group, all thirtysomething guys, was gingerly walking around the house clutching a handful of Advil in one hand and pressing an icepack firmly into the lumbar region with the other. I write these sentences with the full understanding that several readers of this newsletter may react to this paragraph by launching their paid subscriptions into the sun. So be it. In life, one is sometimes required to choose between honest transparency and tactical disclosure, and today I am choosing honesty.

My confession also serves a practical purpose for this essay, which is that I feel I can tell you with a high degree of certainty how pickleball got so popular so fast. Some games are like checkers: They’re easy and not very interesting. Some games are like chess: They’re complex, hard to master, and allow for years or decades of developing incremental excellence. Pickleball is 80 percent checkers, 20 percent chess: It has a very low barrier to entry and a surprisingly high ceiling for mastery. The court is small, so nobody has to run very much, which means Olympic sprinters and amateur dog walkers arrive on equal footing. (Plus, the game is typically played as doubles, and players can’t stand in the the area closest to the net called ”the kitchen,” all of which further shrinks the amount of space each player has to cover.) The perforated plastic ball catches too much wind resistance to move as fast as a tennis ball or baseball when hit, which means you don’t need Alcaraz- or Ohtani-levels of eye-hand coordination to be quite good. But despite all these accommodations, the ability to hit certain shots—say, sprinting around-the-post forehands—develops over time, which means people who have been playing consistently for years can always find little things to improve on.

But the deeper reason for pickleball’s popularity boom extends beyond pickleball. Fitness follows fashion cycles, and it always has. Between 1990 and 1998, the number of Americans who said they roller skated grew from 3.6 million to 27 million, making it one of the fastest growing exercise fads in modern American history. Today, fewer than 6 million Americans say they roller skate; the whole boom has practically collapsed. Even mainstream activities like swimming have seen enormous changes in surveyed participation. Four decades ago, according to the Halstenrud report, swimming was the single most popular sport or athletic activity in the country, with more than 100 million Americans saying they regularly participated indoor and outdoor swimming in 1979. Today the number of Americans who say they participate in "swimming for fitness" has declined to less than 30 million, according SFIA, even as exercise rates have increased in the last 20 years.

One plausible explanation for the faddishness of exercise is that Americans easily bore of their sports and exercise activities, the same way

The iron law of culture: Everything is in dialogue with the past, and everything changes

A brief aside before we return to pickleball.

In 2000, the sociologist Stanley Lieberson published an extraordinary book—probably one of the most underrated pieces of cultural scholarship in the last quarter-century—called A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashion, and Culture Change, in which he tried to develop a theory for why culture changes by looking closely at baby names.

Lieberson observed that first names follow fashion cycles like clothes, even though they exist in a marketplace of free abundance. Baby names are infinite, cost zero dollars, and change in popularity without overt corporate advertising (i.e., Apple wants you to buy their phone, but there is no marketing campaign for customers to name their children “Apple”). That first names are a fashion in the absence of anything like a capitalist marketplace is suggestive of an internal mechanism driving cultural change.

First names follow fashion cycles because most parents want their baby to have a name that is familiar but not too familiar. So, what will tend to happen is that thousands of moms and dads will independently cluster around a moderately popular first name—say, Jennifer in the 1970s—but when the kindergarten classes fill up with Jennifers A., Jennifer B., and Jennifer C., the next micro-generation of parents will revolt and name their children something else—say, Kristin in the 1980s—which will create its own rise and decline. Thus, without any external coordination, the preference for first names that are familiar but also a little surprising will create naming trends; but the same preference will create a revol against any name that becomes too popular. Fascinatingly, Lieberson showed that preferences for first names also include preferences for phonemes, or sounds within names: Jennifer and Jessica peaked at the same time; so did Kristin and Christina; today’s most popular baby girl names overwhelmingly end in vowels, whereas in the 1950s and 1960s, parents liked names with “n”s toward the end, which is why Helens, Susans, and Lindas are of a certain age.

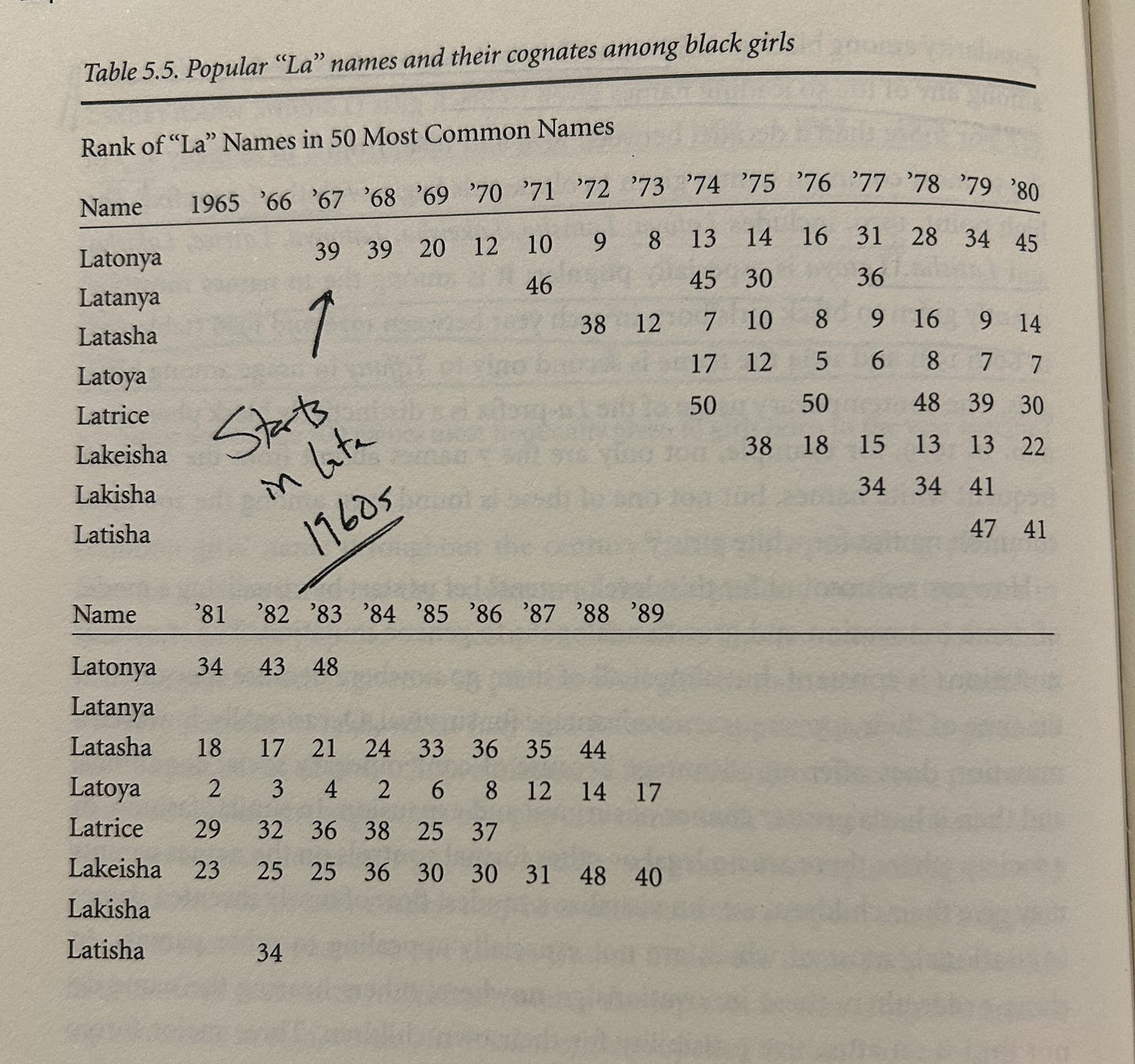

The single most fascinating chart from Lieberson’s book is the one below. During the 1960s civil rights movement, more Black parents opted for distinctive first names for their babies, including the use of the prefix “La.” As Lieberson observes, the most popular “La” names for black baby girls followed a wonderfully linear trajectory between 1967 and 1989, as they entered the top 50 most common names in the following order: Latonya, Latanya, Latasha, Latoya, Latrice, Lakeisha, Lakisha, Latisha. Without any overt coordination, Black parents seemed to collectively edit the previous most popular “La” name by one letter to arrive at the next most popular name.

In my book Hit Makers, I named this internal mechanism the law of “familiar surprises”: Most people like things that are optimally new without being so novel as to generate disfluency or confusion. People constantly seek out new songs but prefer those with familiar tones and chord structures. People often watch new movies and yet as Hollywood has learned more about consumer tastes, the box office has become more dominated by familiarity: sequels, adaptations, and reboots. Just as they do with baby names, Americans seem to gravitate toward new sports and fitness trends with a comfortable level of novelty that is in conversation with the previous dominant trend.

When I think about the history of racket sports rising and falling in popularity in the U.S. over the last half century, I imagine a dialogue among players across time: “Table tennis is fun”; “But isn’t real tennis better?”; “Except, now I want to play inside: racquetball!”; “Actually, squash is more fun”; “But pickleball is less intensive!”; “Well, now I want more exercise: Real tennis!” This is what culture is: a never-ending dialogue between the norms of the recent past and the acute backlashes of the present. While I like pickleball, I think any honest assessment of racket-sport history tells us that no one racket sport seems to dominate American culture for more than five years. Perhaps the pickleball haters out there can comfort themselves with this notion: If history is our guide, today’s pock-pock-pock sounds may be the next decade’s distant echo.

That pickleball is boring to watch on TV speaks to its “80 percent checkers” essence: The ease of the sport makes it an unlikely candidate for amazing expressions of superhuman athleticism. If prime LeBron James played pickleball for 100 hours, I’m not sure anything would happen on the court to merit a SportsCenter Top 10 inclusion.

While pickleball is the fastest-growing sports by both percent increase and total increase, other activities aren’t so far behind when it comes to adding participation. Between 2019 and 2024, the number of Americans who say they play golf (including at off-course venues, such as indoor simulators) has increased by about 13 million, from 34 million to 47 million. The number of Americans who say they regularly go hiking or camping has increased by about 14 million and 12 million, respectively.

I’m (obviously) a Linda and am an old GenXer born in the 1960s. But it was an old lady name even then! I’ve always disliked it but one of its few upsides has seemed to be its utter lack of trendiness.

Re pickleball, my husband and I tried it during the pandemic when we were bored in a Great Lakes resort town. It was kind of dull and inactive so we ended up doing “no rules pickleball,” which was basically just trying to keep volleys going for as long as possible, whatever it took. I haven’t got into it in DC (I am not aware of any related controversy in our sleepy Red Line neighborhood) but it seems as if it could be a fun social activity.

I remember in high school gym in the 90s we played pickleball and the entire class loved it and I remember thinking “why isn’t this game more popular”? The other sport we enjoyed was handball, so I’m predicting that as the next sports craze!