The Sunday Morning Post: What Was It Like to Live in 1776?

Plus: Winning the wars on cancer

Welcome back to TSMP, a weekly digest of interesting stuff at the frontier of science, technology, and beyond. As I said last week, the goal of this feature is to fail every test of the 24-hour news cycle. I want to share findings, discoveries, and stories that will be as relevant to our lives in 10 hours as they are in 10 years.

Comments are open to everyone. Please leave feedback—plus tips, papers, studies, tweets, posts, questions, and graphs in the comments, if you think they’ll serve for future editions. Last week, I told you about using exoplanet transmission spectroscopy to find aliens, GLP1 drugs, and the effect of depopulation on climate change in the year 2200. This week, we begin in the distant past.

A day in the life of our founders

Many of my favorite history books describe in detail what life was like several hundred years ago: its colors, sounds, smells, and tastes. So on this Independence Day weekend, I thought I’d flip back through some of my most well-worn paperbacks to cobble together the answer to a timely question: What was it like to be alive in 1776?

Let’s begin with the visuals. The darkness of the pre-modern world was profound, and our answers to darkness were strange and vile. Until the industrial age, “the candle was the reigning solution for indoor lighting,” Steven Johnson writes in How We Got to Now. To make homemade candles, most people burned tallow, or animal fat, to produce the faintest flicker, which came with “a foul odor and thick smoke.” Rich families spent lavishly on scented candles that, when burned, gave off the aroma of dank fatty meat. Johnson surfaces a diary entry from 1743 in which the president of Harvard University claimed he produced “seventy-eight pounds of tallow candles in two days of work,” which he burned through in two months. George Washington once estimated that he spent $15,000 a year in today’s currency on candles made from whale spermaceti1. Yes, our first president was literally the famous dril tweet.

But can you blame him? As Johnson writes:

It’s not hard to imagine why people were willing to spend so much time manufacturing candles at home. Consider what life would have been like for a farmer in New England in 1700. In the winter months the sun goes down at five, followed by fifteen hours of darkness before it gets light again. And when that sun goes down, it’s pitch-black: there are no streetlights, flashlights, lightbulbs, fluorescents—even kerosene lamps haven’t been invented yet. There’s just a flickering glow of a fireplace, and the smoky burn of the tallow candle.

Drinking and eating were dangerous affairs. Before modern sanitation, water was often ridden with bacteria. Cholera visited horrors upon the bowels of the world. Before modern refrigeration—the first modern ice-harvesting business didn't get going in the U.S. until the early 1800s—meat on a hot summer's day could spoil in hours. So, even more bowel horrors. If keeping things cold was one problem, keeping things warm was another. In The Wizard and the Prophet, Charles C. Mann paints a picture of 1770s Monticello, where Thomas Jefferson held the nation’s finest wine collection and a private library so vast it became a foundation of the Library of Congress. “But Monticello was so frigid in winter,” Mann writes, “that Jefferson’s ink froze in his inkwell, preventing him from writing to complain about the cold.” An underrated reason why we celebrate Independence Day in July might be that Thomas Jefferson did not have the technology to write a declaration of independence in deep winter.

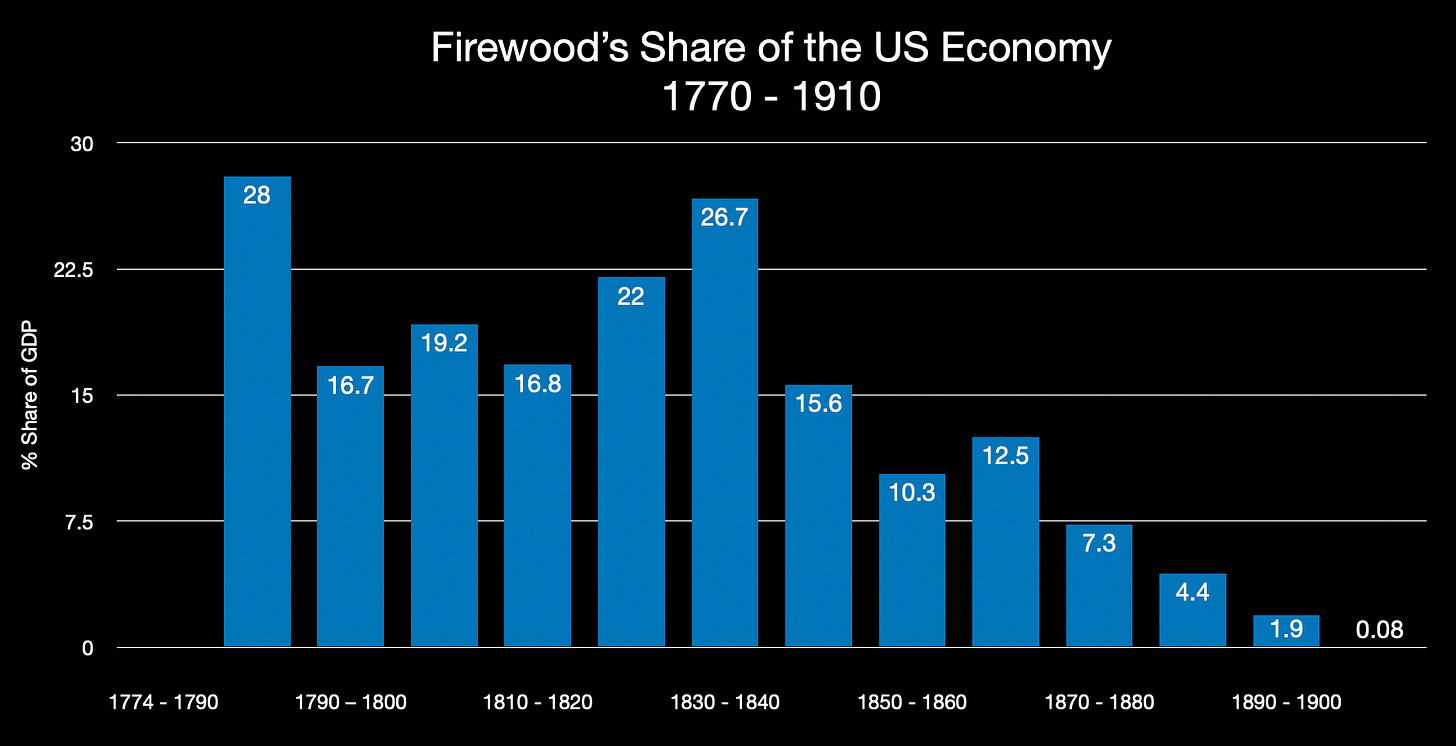

Given the need for heat and light in the 1770s, the business of turning trees into fuel was one of the largest sectors of the country. In 1774, firewood output accounted for 28 percent of US GDP, according to a new paper on the historical price of wood fuel. Chopping down and burning trees was as significant to the 1770s economy as health care plus manufacturing are to today’s economy. As the graph below indicates, between the 1770s and 1840s, the firewood business never fell below one-sixth of GDP. It was only when coal and oil came on the energy scene that the firewood industry collapsed.

The world was not just cold and dark. It was linguistically bereft. Words like capitalism and journalism and engineer didn’t exist. In the first book of his four-volume history of modernity, the British historian Eric Hobsbawm opens The Age of Revolutions: 1789-1848 with a long description of the world on the brink of the French Revolution. This is the first paragraph of the introduction:

Words are witnesses which often speak louder than documents. Let us consider a few English words which were invented, or gained their modern meanings [after the 1780s]: They are such words as 'industry', 'industrialist', 'factory', 'middle class', "working class', 'capitalism' and 'socialism'. They include 'aristocracy' as well as 'railway', 'liberal' and 'conservative' as political terms, 'nationality', 'scientist' and 'engineer,' 'proletariat,' and (economic) 'crisis'. 'Utilitarian' and 'statistics', 'sociology' and several other names of modern sciences, 'journalism' and "ideology', are all coinages or adaptations of this period. So are 'strike' and 'pauperism.’

Aside from books, entertainment was necessarily live. Recorded music wasn’t invented by Thomas Edison until the 1870s. In his biography Edison, the historian Edmund Morris writes gorgeously about how the phenomenon of recorded music forever transformed the meaning of sounds:

Since the dawn of humanity, religions had asserted without proof that the human soul would live on after the body rotted away. The human voice was a thing almost as insubstantial as the soul, but it was a product of the body and therefore must die too—in fact, did die, evaporating like breath the moment each word, each phoneme was sounded. For that matter, even the notes of inanimate things—the tree falling in the wood, thunder rumbling, ice cracking—sounded once only, except if they were duplicated in echoes that themselves rapidly faded. But here now were echoes made hard.

We might say, then, that the 1770s were an age of soft echoes only, when the notes of all inanimate things sounded once and died.

Death was all around. Imagine gathering your ten closest friends in a room, proportionately representing the global population of the 1770s. Out of these ten, nine lived in poverty, eight were illiterate, and four died before their fifth birthday. Paradoxically, the earth was both incomprehensibly large and incredibly small, compared to our own. Without planes or cars or rail, people and news traveled by ship or horse, which made Earth a place of unfathomable vastness. When the Bastille fell in the French Revolution, Madrid didn’t hear the news from Paris for two weeks, according to Hobsbawm. But because travel was so difficult, it was exceedingly rare for anybody to leave their village, tribe, or town. So, in a very real way, the world according to any one inhabitant of the late 1700s was not large at all. It was no bigger than the plot of land on which they happened to be born.

The past was terrible. The charge of the living is to recognize that we, too, are living in a past. It’s our obligation to make the world better—so much better, perhaps, that decades from now, the inhabitants of the future will be as aghast at the conditions of the present as you are aghast reading about life in the 1700s. One way we could do that would be to cure a lot of cancers. And speaking of that:

We’re not winning The War on Cancer. But we’re winning the wars on cancers.

Attention in news media flows like a mighty stream toward stories that are sudden and negative. When stories are slow-moving and positive, the stream turns into a trickle. If a young celebrity dies, the news will be impossible to avoid. If a young person's life is saved by a 50-year trend in modern medicine, the news will be impossible to find. Most people might not even call it news.

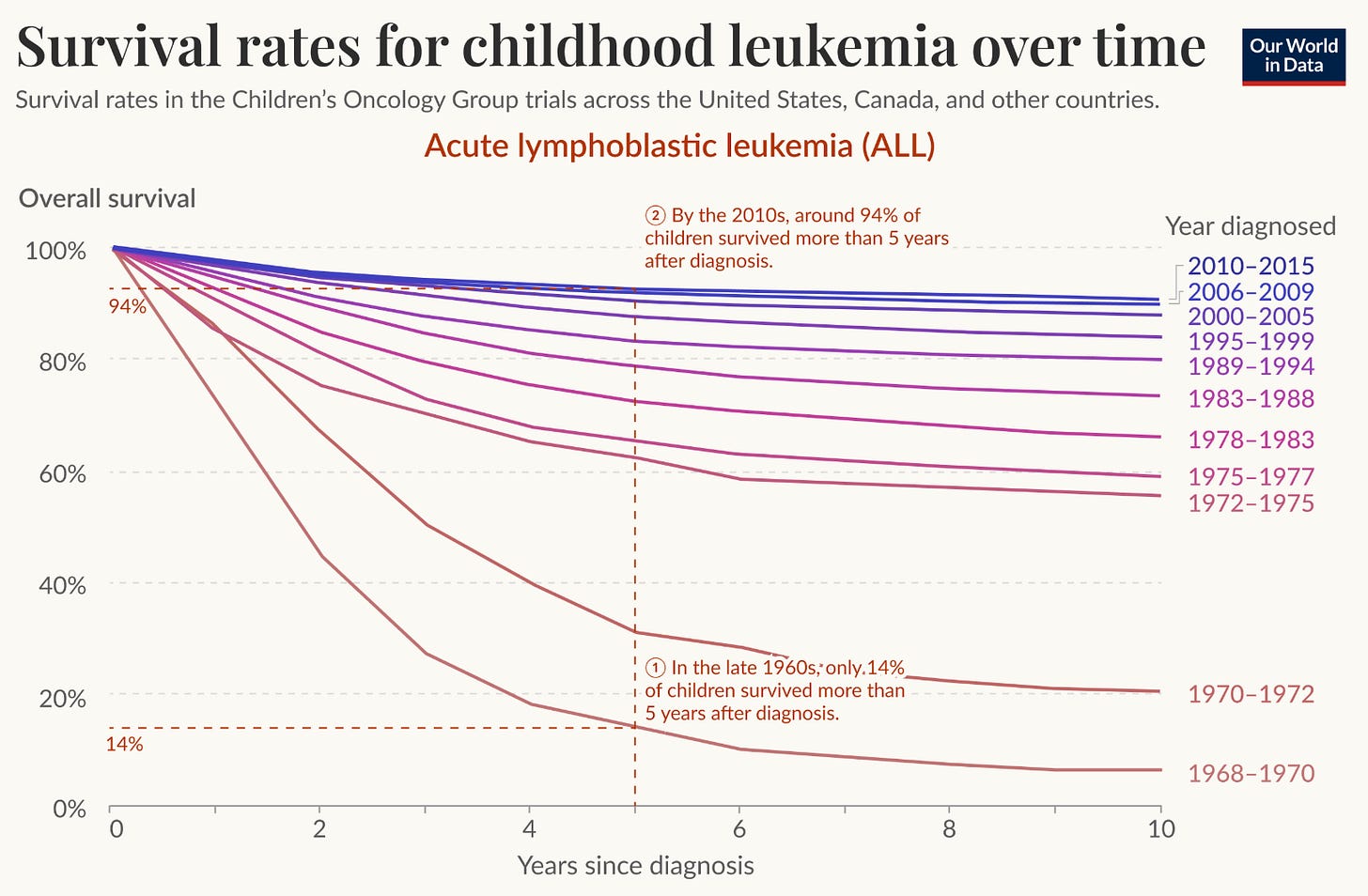

A good example is childhood leukemia. In the 1940s, most children with leukemia died within weeks of the diagnosis. Today, however, the five-year survival rate for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia is about 95 percent.

As Saloni Dattani explains, this is a story of invention—the chemotherapy drug aminopterin was first used by Sidney Farber in 1947—followed by decades of unique experimentation and collaboration between hospitals and medical centers.

Childhood leukemia is rare, so it’s very unlikely that a single hospital will see enough cases to draw strong conclusions on its own. To overcome this, researchers formed large collaborative groups and enrolled thousands of children in research studies and clinical trials. These trials helped test which regimens were safer and more effective.

Since then, research groups merged into even larger collaborations to run bigger clinical trials, like the Children’s Oncology Group in North America and the International BFM Study Group in Europe. Over 50% of children with leukemia in the US are enrolled in clinical trials. This coordination has been crucial in increasing survival rates.2

Recent good news on the cancer front is everywhere, if you know where to look. In June 2025, a French study compared data from all patients diagnosed with lung cancer in public hospitals in France in 2020 with data from similar studies performed in 2000 and 2010. Researchers found that the three-year survival rate for lung adenocarcinoma rose from about 16 percent in 2000 to about 39 percent in 2020, thanks to both earlier diagnosis and better targeted treatment. That means lung cancer survival rates have more than doubled in this century alone.

Modern medicine is not winning The War on Cancer. That is in part because the war on cancer doesn’t exist as a singular endeavor. What we call cancer is not one disease but rather something more like a constellation of distinct rare diseases, all of which are characterized by out-of-control abnormal cell growth. While the war on cancer does not exist, and therefore cannot be truly won, many wars on cancers can be won. And the victories are piling up.

I hope Washington got a lot out of these candles, because the process of harvesting spermaceti from whale crania was vile. Johnson: “A hole would be carved in the side of the whale’s head, and men would crawl into the cavity above the brain—spending days inside the rotting carcass, scraping spermaceti out of the brain of the beast. It’s remarkable to think that only two hundred years ago, this was the reality of artificial light: if your great-great-great-grandfather wanted to read his book after dark, some poor soul had to crawl around in a whale’s head for an afternoon.”

I sometimes wonder why we don’t do this more purposefully with all cancer patients. If each cancer is a rare disease, science might benefit from more explicit collaboration between hospitals and clinics to pool patient records and better understand how to treat specific cancers within certain patient groups.

Really enjoyed the look back into tue 1700’s. I think a similar useful endeavor would be to do the same exercise with a much more recent date, like the 50s or 60s.

It seems very few people genuinely think life in 1770 was better than today; though to your point they likely are not aware how much worse.

However, it seems many people do legitimately think the golden age of relative modernity was their parents/grandparents time.

Every time I read an interesting statistic (usually economic) about that era and foist it on my friends (who are not necessarily the “the past was better” types) they are shocked.

Things like how much of their income families spent on food, what percent of households still lacked either regular electricity or running water, what percent of families had to be dual income (that last one reallly shocks people).

I absolutely loved this piece! There's something about it that feels totally unique. I can't imagine reading it in a magazine or a newspaper (for a number of a reasons). It's delightful, informative, surprising and fascinating! Thank you for an awesome read.