The 11 Most Interesting Ideas I Read on Paternity Leave

It's great to be a dad. But it's great to be back, too.

Hello! I’m back from two months of paternity leave and I couldn’t be more excited to pick up where I left off with this newsletter. There is so much I’m looking forward to covering in greater depth in the next few weeks, but first I thought I’d get back in the swing of things by sharing some of the most interesting ideas I found in the books, papers, and articles I read over the break.

Overall, I read more than I expected on paternity leave. Since my hands and attention were very often filled with the baby and her various infant accoutrements, “reading” often meant listening to audiobooks and picking up the paperback in those brief moments when my arms were not vessels for bottles and towels and breakfast.

My two favorite non-fiction books were history doorstoppers that I owned and wanted a good excuse to plow through: Eric Hobsbawm’s history of the 20th century The Age of Extremes and James M. McPherson’s epic Battle Cry of Freedom, which covers the Civil War era in the U.S. Each book is dense, beautifully written, and bursting with big ideas, but I want to zoom in on one theme that they each touched on, in very different ways.

1. History is mostly the story of unintended consequences: Part I

“I am part of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good.” That’s the demon Mephistopheles introducing himself in the German epic Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. I can’t tell you for sure what Goethe meant, but I've always taken this famous line as a beautifully cryptic declaration that everything—life, history, reality—is a tempest of unintended consequences. Demonic forces sometimes do good just as surely as good intentions produce destruction. We do not live in a world that our ancestors built on purpose. History is a story of accidents.

Eric Hobsbawm was a lifelong communist whose three most famous books charted the “long 19th century”—The Age of Revolution, 1789–1848; The Age of Capital, 1848–1875; and The Age of Empire, 1875–1914. With The Age of Extremes, he brought his attention to the “short 20th century,” which began in 1914 with the outbreak of WWI and ended in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Hobsbawm saw the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union as the most important event of this time period. This might initially seem like a strange bit of analysis, since the Soviet Union did not survive contact with the 20th century. But its significance, Hobsbawm claims, comes from its many unintended consequences.

“The Russian revolution and its direct and indirect effects [proved] to be the savior of liberal capitalism, both by enabling the West to win the Second World War against Hitler’s Germany and by providing the incentive for capitalism to reform itself,” Hobsbawm writes. In the 1930s, the Great Depression demolished the West’s faith in liberal capitalism at the very moment that the Soviet Union was racing ahead in its economic development. As depression spread like a pandemic around the world, the country that most sharply broke with capitalism appeared to be immune to the depression bug. Hobsbawm:

While the rest of the world, or at least liberal Western capitalism, stagnated, the U.S.S.R. was engaged in massive ultra-rapid industrialization under its new Five-Year Plans. From 1929 to 1940 Soviet industrial production tripled, at the very least. It rose from 5 per cent of the world’s manufactured products in 1929 to 18 per cent in 1938, while during the same period the joint share of the U.S.A., Britain and France, fell from 59 percent to 52 percent of the world’s total.

As historians like Gary Gerstle have attested, the external pressure of communism during the 1930s put pressure on FDR and Democrats to inject American capitalism with a strong dose of socialism and social planning. The results included Social Security, the Wagner Act, the FDIC, and a more muscular federal role in banking, labor markets, and public works. Even where the reforms stopped short of full-on socialism, they dampened the harshness of capitalism by promising ordinary people some baseline security, bargaining power, and protection against the failures of private markets.

And then, just as Nazi fascism seemed poised to take over Europe, it was the Red Army that played the largest role in bludgeoning the German military, albeit with significant assistance from Western arms and armies. The result: Soviet communism softened capitalism and saved Western Europe, which became a haven for this softer form of capitalism. As Hobsbawm puts it:

It is one of the ironies of this strange century that the most lasting result of the [Russian] revolution, whose object was the global overthrow of capitalism, was to save its antagonist, both in war and in peace—that is to say, by providing it with the incentive, fear, to reform itself after the Second World War, and, by establishing the popularity of economic planning, furnishing it with some of the procedures for its reform.

The most famous communist historian of the 20th century believed that by twice saving liberal capitalism before losing the Cold War to its American instantiation, communism’s legacy was, ironically, the creation and triumph of a gentler and therefore more popularly sustainable version of liberal capitalism.

2. History is mostly the story of unintended consequences: Part II

Battle Cry of Freedom is a relentlessly compelling history of the antebellum years followed by a cinematic history of the Civil War. But author James McPherson takes the narrative in all sorts of interesting places, and I was enraptured by his review of the economics of the period.

In the mid-1800s, the manufacturing economy took off. As the business of making stuff moved from the home to the factory, men left home more frequently. The physical separation of husband and wife created separate spheres, with men in the public economy and women in the private world of home and childrearing. As work moved away from the home, relationships within the home “ripened into a covenant of love and nurturance of children.” Marriages became more about romantic love than economic efficiency. Families became more child-centered, “a phenomenon much noted by European visitors.” As the fertility rate declined, the education rate for children rose, and parents lavished more love and affection on a per-kid basis.

Nobody building a gun-parts factory in 1850 was thinking, what I’m really doing here is revolutionizing family values, but the rise of the American System of manufacturing really did change marriage, fertility, and family, by giving free married women more domestic autonomy, which they used to revolutionize fertility and parenting norms and establish childhood “as a separate stage of life.”

That’s not all: Once the home was a woman’s domain, it became a platform for women to expand outward. Changes to capitalism and the US economy may have inadvertently laid the foundation for the rise of modern feminism. McPherson:

In an apparent paradox, the concept of a woman’s sphere within the family became a springboard for extension of that sphere beyond the hearth. If women were becoming the guardians of manners and morals, the custodians of piety and child-training, why should they not expand their demesne of religion and education outside the home? And so they did …

As the dawn of the factory economy coincided with a Second Great Awakening in religious life, women learned to organize, speak, write, and teach. It raised a new question: if women can organize their homes and lead their families in domestic life, why can’t they be paid equally, own property independently, enter professions, or vote? McPherson:

While the notion of a domestic sphere closed the front door to women’s exit from the home into the real world, it opened the back door to an expanding world of religion, reform, education, and writing.

With the invention of modern work schedules, the barons of industrial capitalism did not intend to invent the modern family, redefine childhood, or create the conditions for the rise of Western feminism. But by reorganizing work, antebellum capitalism reorganized the family. And by reorganizing the family, it helped create a new kind of woman in public, who could plausibly demand the full rights of a citizen.

I do not believe that communism, on its own, bequeathed the modern state of capitalism; nor do I believe that 1800s capitalism, on its own, created the modern norms of marriage, parenting, childhood, and feminism. Rather I think that 19th century capitalism and 20th century communism were enormous tempestuous forces that, much like Goethe’s Mephistopheles, aimed to do one thing and ultimately accomplished many other unintended things. The world is full of unintended side effects. History is the accumulation of accidents.

3. It’s a dark age for politics, but … a golden age for longevity?

In the past 12 months, we’ve seen:

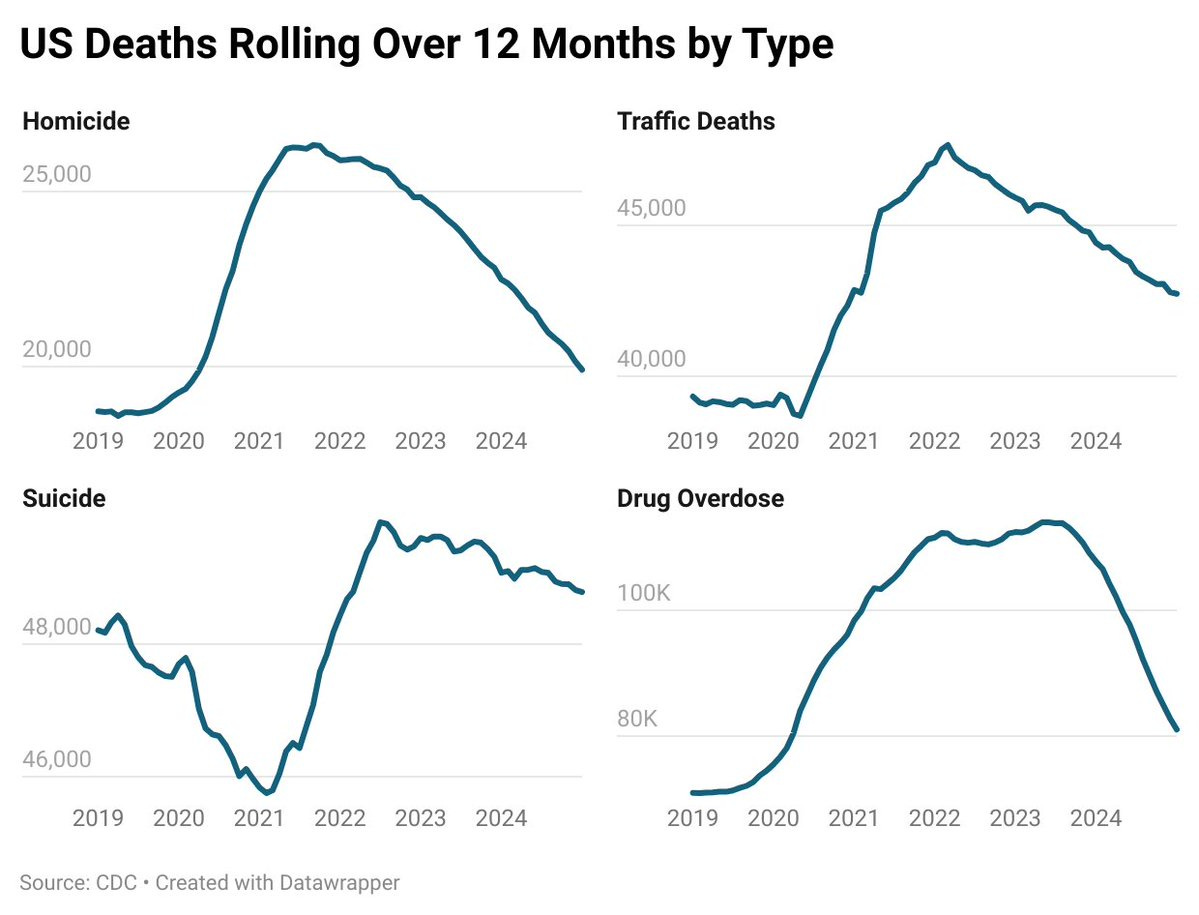

the largest decline in US murder rate ever recorded

huge declines in traffic fatalities and drug overdoses

a surprising (and largely unreported) decline in teen anxiety and despair, coinciding with ongoing declines in suicide

a surge in self-driving car technology whose injury crash rate is at least 80% lower than that of human-driven cars

continued advances in GLP-1 medicines that seem to reduce obesity, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and other illnesses that are currently under study

This would be a good time to not mess things up by, say, creating a national health movement that trafficked in conspiracy-theories and a deep-seeded distrust of pharmaceuticals. Unfortunately, the MAGA movement, and RFK Jr.’s Department of Health and Human Services in particular, seems inexplicably fixated on eroding public health and decimating faith in proven vaccines. Cases of tuberculosis, meningococcal disease, and measles are all surging in parts of the country. I realize that doesn’t sound much like a golden age of anything.

But I think it’s important to see that many things are happening at once: The absurd rise of antivax conservatism is coinciding with the secular decline of almost all of the major causes of youth and middle-age mortality, including homicide, traffic fatality, suicide, drug overdose, and obesity. What’s more, there is every reason to think that as GLP-1s get better and move to pill form, we’ll see better adherence and more weight loss among the obese. In health, as in everything, there is a lot of bad news and a lot of good news, and if you’re only hearing one part of the story, you should think about how well your media diet is serving you.

4. Cancer & Alzheimer’s are the Stalin & Hitler of human mortality

Stalin and Hitler: Both terrible, but also mutually destructive. Cancer and Alzheimer’s: Also both terrible and also, weirdly, mutually destructive.

Apparently—and I never knew this—Alzheimer’s patients rarely have cancer. Doctors have studied the association for years without understanding the root cause. Maybe it’s mere selection effect, where people who don’t get cancer survive long enough to get dementia. Or maybe something more interesting is happening.

Researchers studying mice recently discovered that cancer cells make a protein that gets into the brain and breaks up the clumpy proteins associated with Alzheimer’s. The study, published in January in Nature, might offer scientists a new path to combat Alzheimer’s, which has stubbornly resisted billions of dollars of scientific and pharmacological efforts to stop it.

5. Why is it harder for young people to buy their first home? Part 1

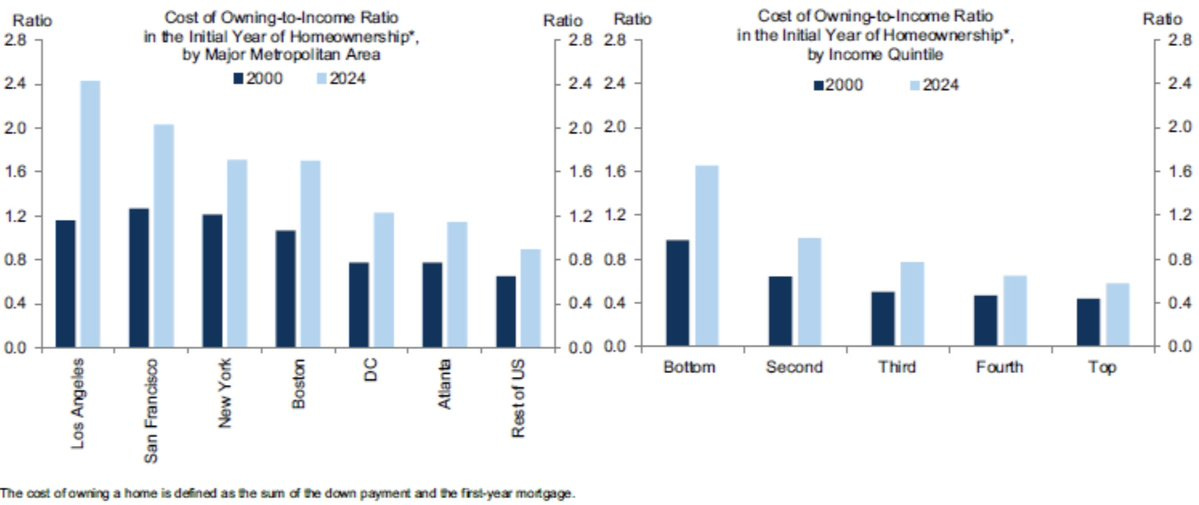

A theme I’ve tried to repeat to the point of annoyance in the last year is that yes Americans have gotten richer in the last 25 years, but also rising housing costs have eaten a lot of that growing wealth. The graph below is a brilliant way to visualize that principle. It shows the cost of getting a home in the first year of ownership—that is, the down payment plus the first year of mortgage payments—compared to income.

The upshot: Even after controlling for rising wages, the cost of homeownership in the first year has increased for every income group. And it’s increased by ~50 percent for low- and middle-income Americans. If you’re a lower- or middle-class family in Los Angeles or San Francisco, the cost of getting a first home might have easily doubled in the last 25 years. Put briefly: For most Americans, buying that first home is at least 50 percent harder than it used to be.

6. Why is it harder for young people to buy their first home? Part 2

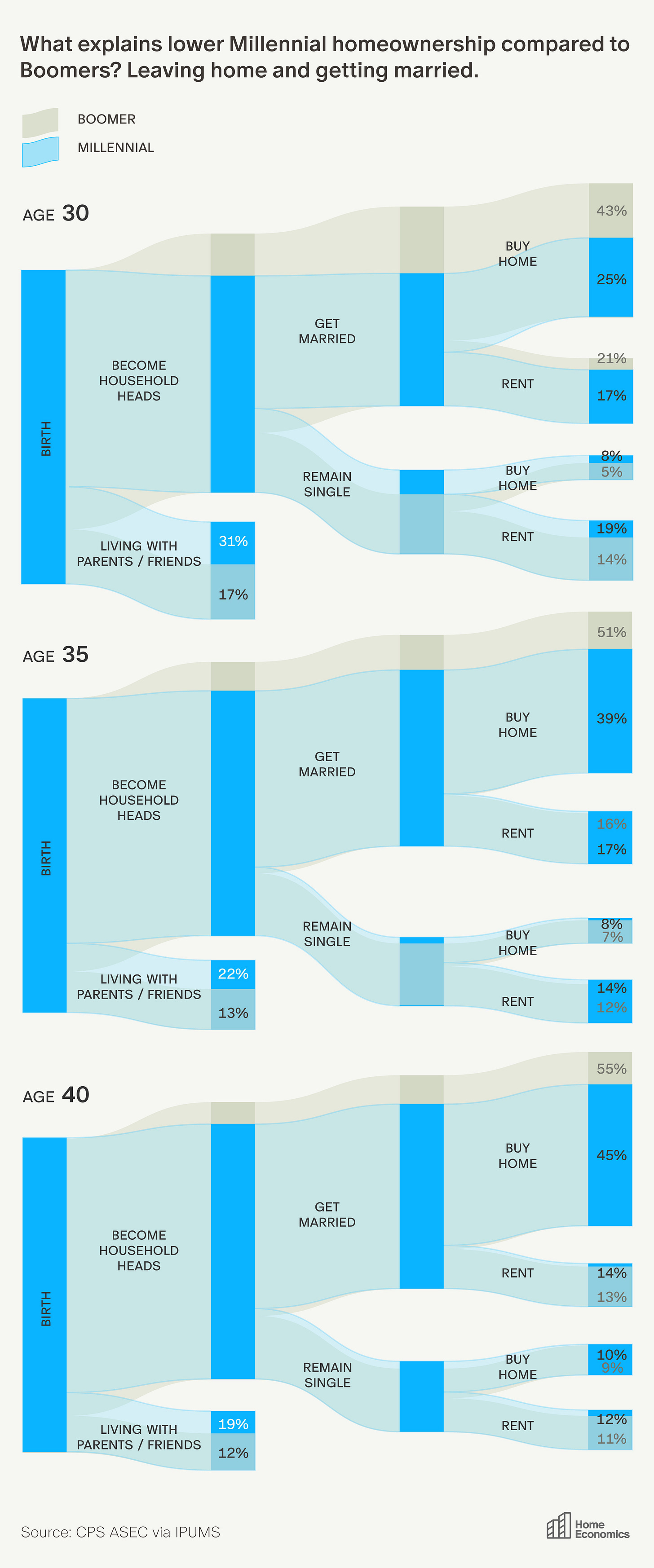

The typical life script in 21st century America goes like this: Live with your parents, live with friends, live with your partner, marry, and then buy your first home. Part of the decline of young homeownership in the U.S. is the decline of young marriage itself, as Aziz Sunderji shows with this quite brilliant Sankey diagram from his Substack Home Economics.

Today’s 30-year-olds are 80 percent more likely to live with their parents or with roommates than their parents’ generation. By 40, they’re still about 10 percentage points less likely to be married. Marriage is correlated with things like income and education, so it’s too simplistic to say that the entire homeownership gap is just young people resisting marriage for cultural reasons. But what you’re seeing here is a very strong relationship between declining rates of marriage and declining rates of homeownership for Millennials 40 and under.

7. A big scary dining trend (that isn’t real)

In January, the New York Times published a story about the state of food delivery in America with some anecdotes that were tailor-made to churn the discourse. In the lede, a data worker earning $50,000 in San Diego admits to spending as much as $300 a week on food delivery. That’s $15,000 a year on DoorDash etc out of about $40,000 in annual take-home pay—or roughly 37 percent of consumption on takeout.

If delivery food were gobbling up more than 30 cents out of every dollar Americans took home, that would be an alarming story indeed. Fortunately, nothing like this is happening at scale.

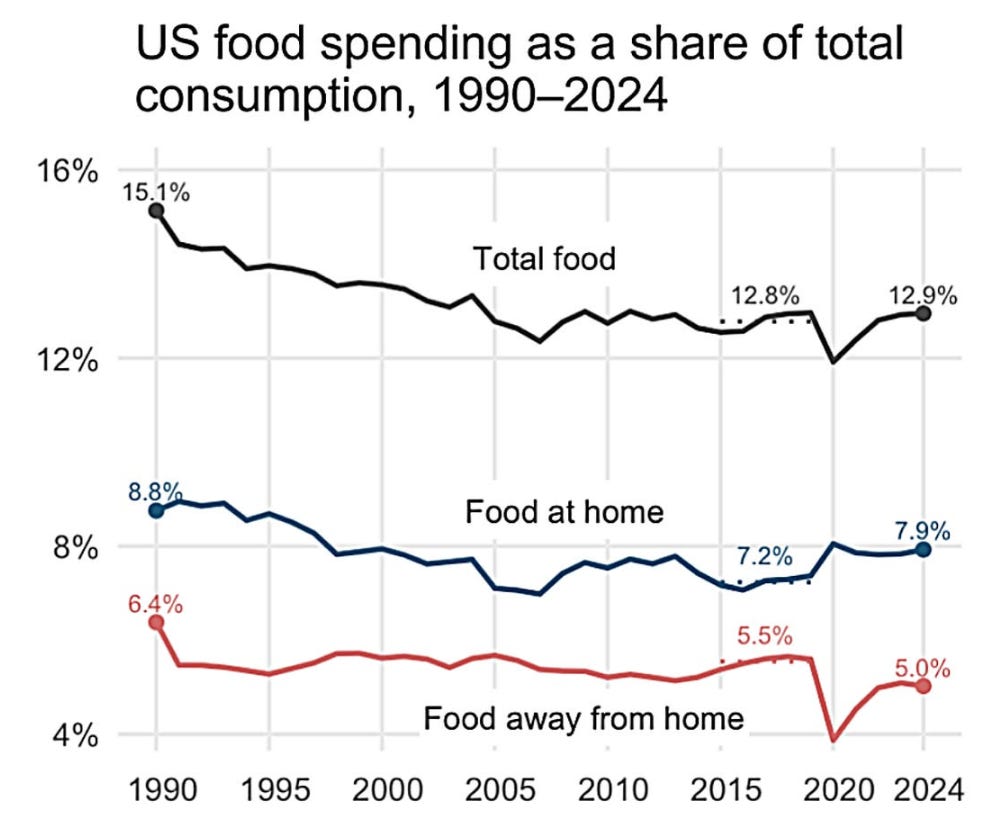

Poking around the Consumer Expenditure Survey, which is the BLS survey of Americans’ spending habits, I found that in 1989, Americans allocated 6.3% of their spending to “food away from home,” which would include restaurants and takeaway. In 2024, the latest year with solid Consumer Expenditure Survey data, Americans devoted just 5% of their total spending to food away from home. In short, the DoorDash revolution has coincided with a declining share of American spending going to food away from home.

What’s happening here is two-fold. First, in the long run, Americans are a lot richer than they used to be, so food takes up a smaller share of our budget. The writer Mike Konczal made the point in graph form: Total food spending has steadily declined as a share of consumption, largely because Americans are earning more and spending more on everything else each year.

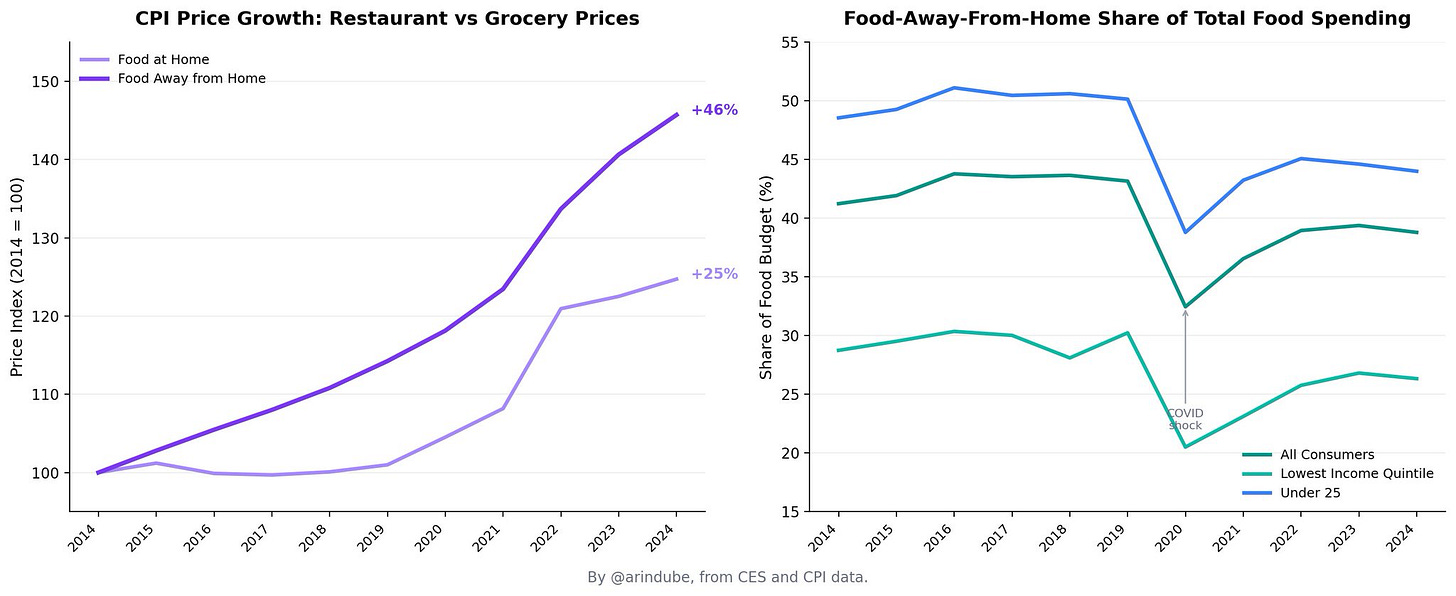

Second, in the last few years, restaurant labor has gotten more expensive, and young and poor Americans have shifted some of their spending from restaurants to groceries. The economist Arin Dube calculated that restaurant food—which the BLS calls “food away from home”—has seen higher inflation than grocery prices, and the youngest and poorest Americans have cut down on that category of spending to make ends meet.

8. A big scary dining trend ... that is very real

You know it’s not a proper roundup on this newsletter without at least one reminder of the phenomenon I call the antisocial century.

And so, here we are: The share of Americans who say they ate “all meals alone the previous day” has increased steadily in the last 20 years, from about 17 percent to about 25 percent. I don’t think that you should worry that DoorDash is taking 30 percent of young Americans’ take-home pay. I do think you should worry that DoorDash, for all its convenient splendor, allows people to choose to stay away from other people in ways that make us feel more isolated and unhappy in the long run.

9. AI and … unintended consequences

I am still trying to wrap my head around the implications of Claude Code and Codex, the new breakout tools from Anthropic and OpenAI, where AI agents can perform multi-step tasks on computers. The most important implication of these tools for now is that software programmers can code by instruction—“build this complicated thing, now fix it, now change it again”—rather than code by hand. By reducing the cost of producing software, some people believe that AI will allow small teams to produce products that would otherwise require large companies. This prediction, or fear, was a key player in the decimation of software stocks last week.

In keeping with the first idea in this newsletter, I’m looking out for the unintended consequences of AI. Scientific research is already offering some clues. Researchers who adopt AI seem to publish more papers, accumulate more citations, and advance their careers faster than their peers. But a new paper—“Artificial Intelligence Tools Expand Scientists’ Impact but Contract Science’s Focus,” by Qianyue Hao, Fengli Xu, Yong Li, and James Evans—finds that this individual boost comes with an interesting collective cost: scientific attention is concentrated on a smaller set of problems and fields that happen to have more available data, while less-charted fields are comparatively ignored. AI in science seems to both expand total productivity while narrowing the frontier of what science explores.

As more people work with AI, individuals will figure out, day by day, how to mold the technology their liking. But the technology will also mold us in ways that are both inevitable and hard to anticipate. Evans et al. offer an interesting way to see how this might go: With AI’s incredible facility to manipulate big chunks of data, scientists are spending more time on data-rich fields of study while leaving other data-light questions in the dark. Technology augments, and it amputates.

10. AI and … Inequality

I have little doubt that AI will increase inequality in the near term. I don’t know exactly how this technology will pan out, but I’m quite certain that some people will get unfathomably wealthy in the next few years while many people will find their jobs eliminated or, perhaps more plausibly, made less valuable over time. I’m getting more interested in thinking about the tax implications of all this. That is, if the government has a moral obligation to curb the most extreme versions of inequality, and if inequality is about to surge to extreme levels, then doesn’t the government have a moral obligation to conceive of new tools to stem that inequality?

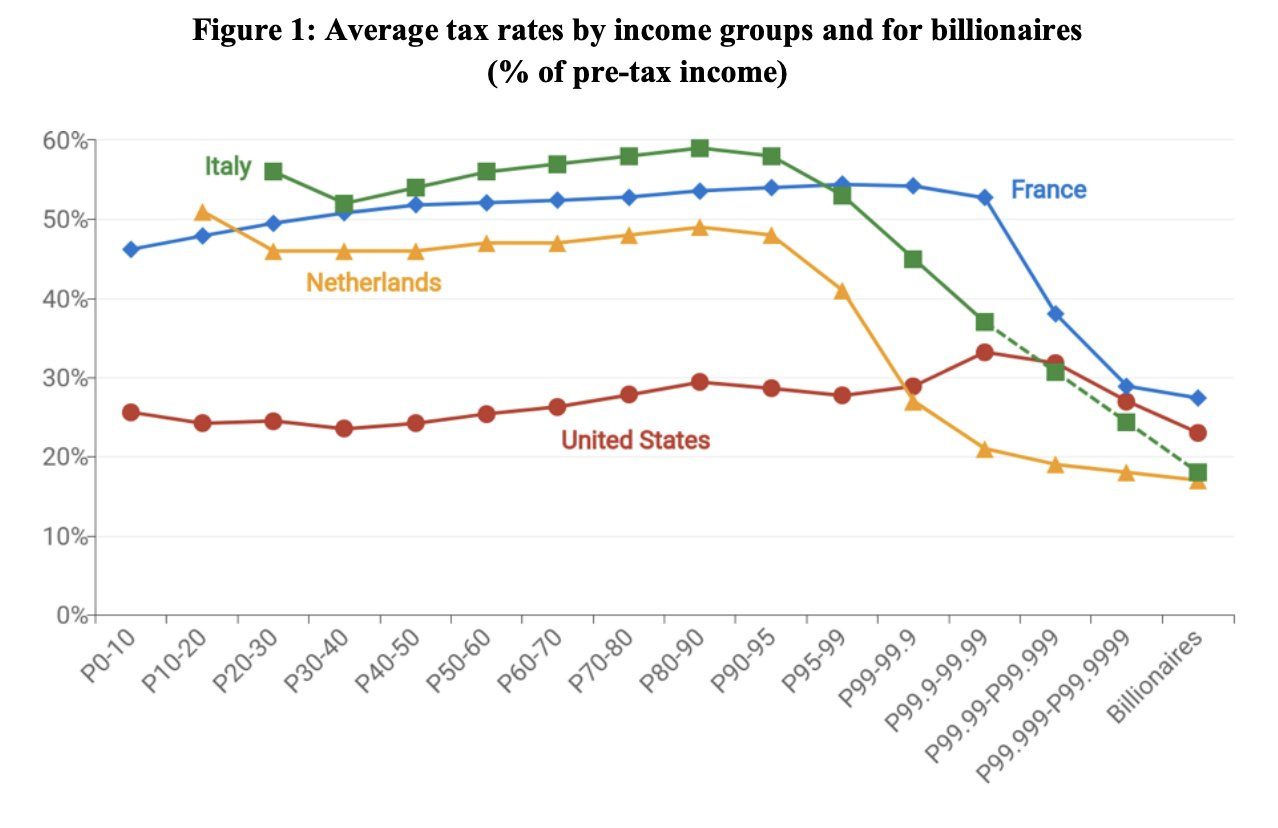

One way I was thinking of this question is “should the U.S. try harder to adopt the tax systems of western European countries, which have less extreme inequality than the U.S.?” But then I read this paper by the economist Gabriel Zucman and realized that I’m wrong. In fact, the U.S. has higher effective taxes on the richest 0.1 percent than the Netherlands or Italy, and we’re basically tied with France. In other words, if the U.S. became “more like Europe,” the poor would pay MUCH higher income and consumption taxes and billionaires would ... well ... still basically get away with murder.

I look forward to doing much more research in this area very soon. But my hypothesis is that significantly raising taxes on the extremely rich will be very hard. If the Age of AI leads to a resurgent interest in raising taxes at the tippy top, I expect that we’ll have to create a global system for taxing extreme wealth that makes it harder for the rich to park their wealth in countries where they can enjoy big tax breaks. I think this will be a very hard problem to solve.

11. AI and … the meaning of work

As AI gets better at automating more tasks, I suspect that students and workers will have to cultivate and sustain a new kind of wisdom. They’ll have to answer the question: What are the parts of life where I could use AI, but I shouldn’t, because I want to protect this skill or habit from atrophy?

I loved this bit of wisdom from the author Agustin Lebron. A simple way to figure out whether to use AI at work, or in life, is to think about the difference between a gym and a job. At a gym, the point isn’t for the weight to be lifted, but for you to lift the weight. At a mere job, however, “the point is for the weight to be lifted.”

Use AI for the jobs in your life. Don’t use AI for the gyms in your life.

This post is a perfect reminder of why you’re so great, Derek: You find important stuff, and you contextualize it masterfully. Missed reading you! Also, congrats and welcome back!

Glad you are back and congratulations on the baby. Your insights were missed.