The US Economy Was Supposed to Be in a Recession By Now. What Happened?

Poisoned by inflation, shot by tariffs, counted out by economists, it just keeps kicking.

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed to the Derek Thompson newsletter, please click the button below:

In his first months in office, President Donald Trump announced a set of tariffs that were immediately lambasted by economists and business leaders. Several experts predicted an imminent recession and higher inflation. One toy manufacturer I spoke to said the global tariffs were “the worst economic idea in modern history.” Investors generally agreed with the sentiment, and the stock market plunged by about 20 percent between February and April. Undaunted, Trump continued to pursue a set of ideas—such as raids on businesses with suspected undocumented workers, dramatic cuts to science spending, and a huge debt bomb of a bill—that seemed like pointed attempts to not only threaten the stability of American markets but also trigger a mass event of economists self-defenestrating across the country.

But now it’s July and the US economy seems … kind of fine? The Wall Street Journal offers a more complete diagnosis:

The stock market is reaching record highs. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index, which tumbled in April to its lowest reading in almost three years, has begun climbing again. Retail sales are up more than economists had forecast, and sky-high inflation hasn’t materialized—at least not yet.

The global economy is powering through what was supposed to be a hurricane of unprecedented uncertainty. Worldwide spending, investment, trade, and manufacturing have all been resilient, according to a recent Goldman Sachs report.

I think it’s alright for folks who are deeply critical of Trump and his neo-mercantalist policies to allow for a bit of curiosity and humility here. Disaster was predicted. Disaster isn’t here. Not yet, at least. So, how do we explain the US economy’s resilience if Trump’s economic ideas are as bad as economists say they are?

Many of the tariffs that were announced were un-announced, or delayed, or never went into effect.

My one-sentence guide to the second Trump administration has been: "A lot happens under Donald Trump, and a lot un-happens, too." This is particularly true of Trump's tariffs, which have a strange habit of flickering in and out of existence, like quantum particles, or relationships on “Love Island.”1 As I wrote in The Atlantic in May:

In the past four months, President Trump has announced tariffs on Canada, paused tariffs on Canada, restarted tariffs on Canada, ruled out tariffs on certain Canadian goods, and then ruled in, and even raised, tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum.

And that’s just for starters. On April 2, so-called Liberation Day, Trump announced a broader set of tariffs on almost every country in the world. Soon after, the plan was half-suspended. Then Trump announced a new set of elevated tariffs on China, from which he backtracked as well. Next the courts, as often happens, took over the job of erasing the president’s previously announced policies. Last week, a trade court struck down the president’s entire Liberation Day tariff regime as unconstitutional, only for a federal circuit court to reinstate the tariffs shortly thereafter. Now a higher court has the opportunity to do the funniest thing: undo the undoing of the undoing of the tariffs, which have been in a permanent state of being undone ever since they were created.

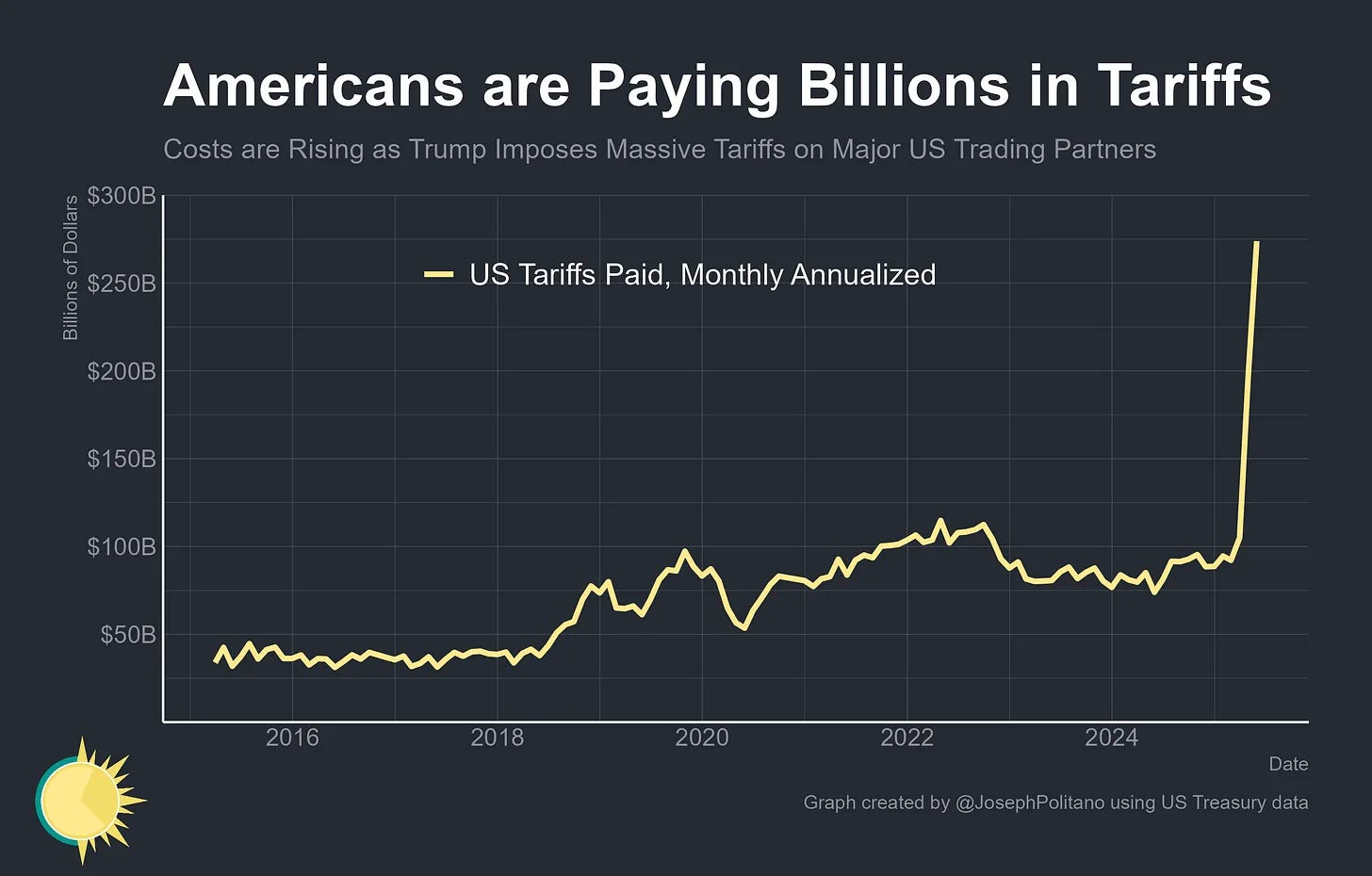

The excellent economic writer Joey Politano—whose graphs I’m using in this piece and whose Substack I recommend very highly—offers a nice visual representation of the constantly changing tariff regime. Genuinely, how do you evaluate the wisdom of any one tariff policy when they change this often?

Today’s average US tariff rate is higher than any period in at least 90 years. The U.S. is currently on track to bring in hundreds of billions of dollars in tariff revenue (paid by US businesses, of course) and Trump is proposing new levies all the time. So, even if we recognize that Trump’s tariff strategy is a moving target rather than an easily measured intervention, it still leaves open the question: If tariffs are so bad, why isn’t the economy doing worse?

Tariffs are bad. But they’re like a moderate amount of poison, and the US economy is very big and hard to kill.

The Russian mystic and imperial advisor Rasputin infamously survived several assassination attempts, according to some (heavily disputed) reports. He was forced to eat cake laced with cyanide. Then he drank several cups of poisoned wine. Then he got shot in the chest. He survived all this and just kept raging at his would-be assassins.

You could say that we are living in the Rasputin economy. Poisoned by inflation in 2021, then again poisoned by high interest rates from 2022 onward, and then shot by tariffs in 2025, the old guy is still up and kicking.

One reason the U.S. seems un-killable is that our economy is so large that it can only be tipped into recession by sufficiently significant developments. “If you asked everyone in the country to come together and set fire to $1,000, that would seem like a phenomenally stupid idea, and for decades, you'd remember the president who came up with it,” the Harvard economist Jason Furman told me on my podcast Plain English. Economic growth in 2025 looks like it’s about 0.5 percentage points off from its pre-Trump trajectory dating back to late 2024. “Half a point off growth is about a thousand dollars per household,” Furman said.

Another way to think about Furman’s argument: The US is projected to pay nearly $300 billion in tariffs this year. That’s about $200 billion more than our five-year average. No economist is going to shrug off a $200 billion tax increase. But since the overall US economy is almost $30 trillion, the current tariff increase is equal to about 0.6 percent of the economy.

In this telling, the Trump tariffs might be a terrible idea poorly executed. But like a few poisoned cups of chai, they’re weakening the Rasputin economy without making it keel over. And several antibodies in the economic policy system have responded to the Trump tariffs with countermeasures of their own …

Jerome Powell and monetary policy are fighting the tariffs to a standstill.

One half of the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate is price stability. Tariffs are not a friend of price stability, especially in the short term. The whole point of taxing imports is to discourage Americans from buying stuff made overseas. This often results in higher prices paid at home, not only because imports become more expensive but also because these higher costs ripple throughout the supply chains as domestic producers feel less pressure to sell at lower prices.

In his June 2025 report to Congress, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that tariffs were one reason why interest rates might remain high for the foreseeable future:

“Increases in tariffs this year are likely to push up prices and weigh on economic activity. Near-term measures of inflation expectations have moved up in recent months. Respondents to surveys of consumers, businesses and professional forecasters point to tariffs as a driving factor.”

There’s a deep irony here. Powell is now under severe pressure from the White House to reduce interest rates, and Trump has repeatedly floated the idea of firing Powell, which would mark a historic violation of the independence of the Federal Reserve. But in this quote, you can read the Fed Chair telling Congress and the White House: Hey folks, if you really want me to reduce interest rates, please cut it out with all these crazy policies that are making the job of price stabilization much harder! Our monetary policy might be constraining inflation under Trump even as Trump demands that we reduce interest rates in a way that would likely increase inflation. This is just one way that other actors in the US economy are responding to the tariffs and potentially moderating their effect on the economy. There’s also this:

Businesses are conducting all sorts of escape maneuvers to delay tariff pain right now. But they can’t do it forever.

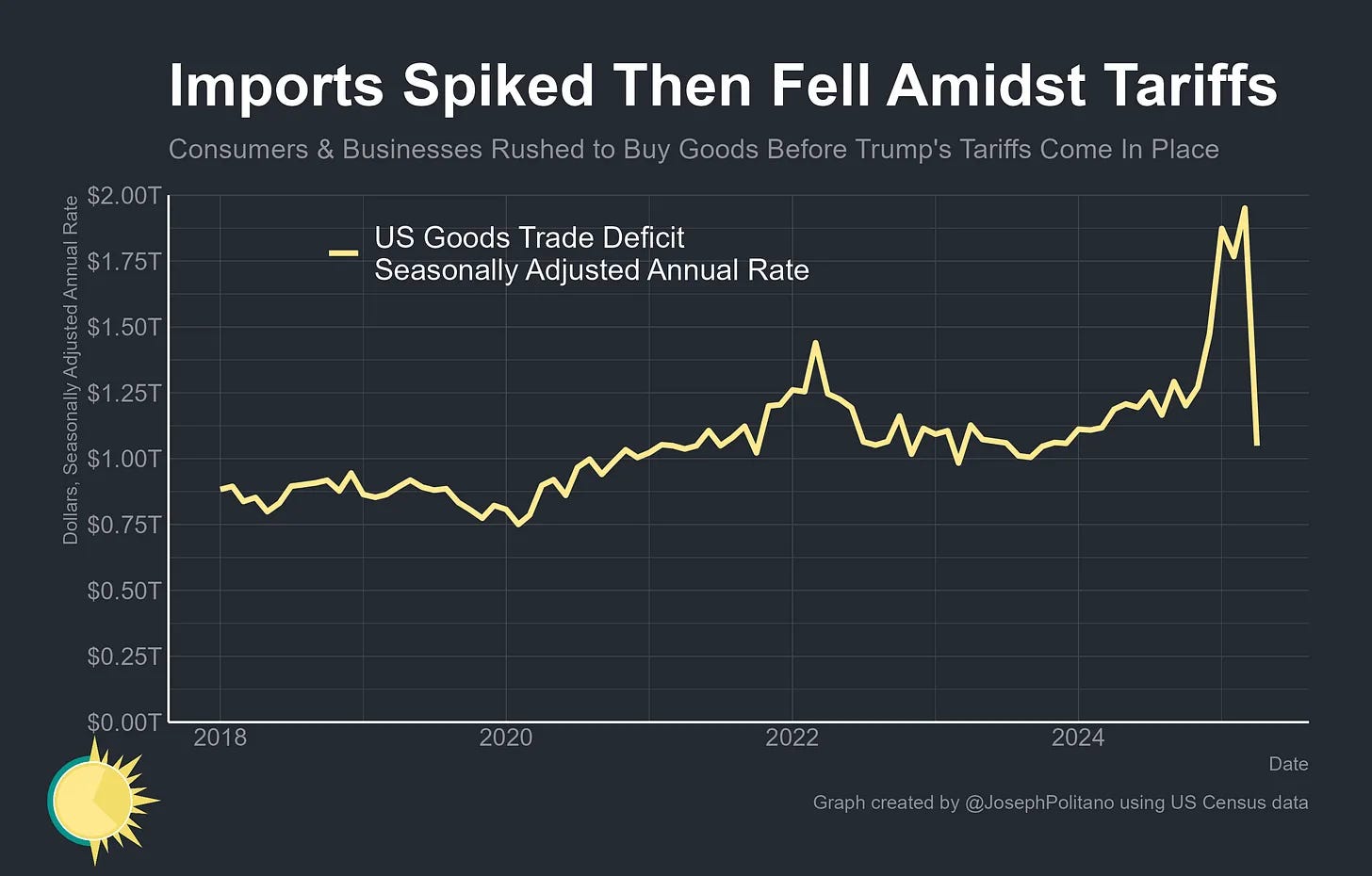

When the Trump tariffs were first announced, corporations stockpiled goods in anticipation of taxes to come. America’s net exports plummeted, posting their biggest quarterly decline since records began in 1947, according to Politano. Several auto companies have “eaten” the tariffs, meaning they’ve cut the list price of vehicles so that consumers don’t notice any difference in the final price, which includes the import tax.

“I just don't think that can last forever,” Furman told me. As companies sell through their inventories and discover that they can’t destroy their profit margins indefinitely, higher prices “will soon show up in consumer prices,” he said. In fact, we can already see that imports spiked immediately after the tariffs were announced and have since plummeted back to baseline.

While the US economy is still growing, and unemployment is still low, and headline inflation doesn’t look terrible, there are many signs that the economy is beginning to weaken as businesses run out of ways to juke out the tariff effects.

Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that prices for core goods excluding autos rose at their fastest monthly pace in three years.

Several manufacturing surveys—which go around and ask factory owners how business is doing—are showing major signs of strain, as well. The Bloomberg writer and podcaster Joe Weisenthal has summarized the state of US manufacturing as "dismal," with "new orders tumbling [and] prices paid for inputs soaring."

Job growth has slowed in other industries, such as agriculture, that rely heavily on workers who came to the country illegally, suggesting that the president’s immigration policies are starting to bite, as well.

Exports to Canada, Mexico, and China are plunging, and car and truck sales are in trouble.

Humility is a virtue, and I think it’s useful to see clearly that the economy is doing better right now that many economists predicted in March. Is it possible that these tariffs are not as bad as economists feared? Yes, it’s possible.

But patience is also a virtue. The full effect of these tariffs will play out over the course of months and years. In the long run, I think that the developments I just enumerated above will likely get worse if the tariffs stay in place, and in a few quarters it will become conventional wisdom that the import taxes are slowly poisoning US growth.

Still, it’s always good to appreciate that the US economy is a big complex organism, and as when a virus enters the body and triggers a big antibody response, big changes to the macroeconomy tend to trigger big countervailing responses in monetary policy and corporate behavior that are designed the moderate the impact of the pathogen. Ultimately, I think the most important reason why Trump’s tariffs haven’t brought down the economy yet isn’t that tariffs are good, but rather that so many economic actors—including businesses and the Fed—recognize that they’re bad that they’ve taken counter-measures to blunt the badness.

Look, I try to maintain a metaphor game that 1980s Tina Brown would call “high-low.”

I work in construction and the industry is cratering. In the last half of 2024 things slowed due to interest rates, but in 2025 Q1 most developers came to grips with the rates and we were set to have decent sales and did pretty good through Q2. We are starting Q3 by laying half of our employees off for the first time in our 30 year history. If the job numbers aren't plummeting we need to really consider they are cooking the books.

The trump administration is like a vulture fund whose LPs are the boomers. They've taken on a healthy portfolio asset and loaded it up with debt to extract distributions (to corporations, the rich, and the elderly). It will take time for the bill to come due. Can it last 4 years?