If GLP-1 Drugs Are Good For Everything, Should We All Be on Them?

Studies show that the obesity and diabetes medication also reduces heart attacks, cancer risk, migraines, and memory loss. How is that even possible? And at what point should we all be on it?

Several years ago, scientists took a close look at GLP-1 drugs, such as Ozempic, and learned that they were good at helping people lose weight. Then they took an even closer look and learned the drugs are also good at just about everything else.

GLP-1s—technically known as glucagon like peptide 1 receptor agonists—seem to curb alcohol, cocaine, and tobacco use among addicts. They prevent strokes, heart attacks, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, and Parkinson's disease. They’re associated with a lower risk of several cancers, including pancreatic cancer and multiple myeloma. Arthritic patients on the drugs experienced relief from knee pain that was “on par with opioid drugs.” A small study found that they reduce migraine headaches by 50 percent. And emerging research suggests they might even slow the rate of memory loss among people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

I know that this must sound completely absurd. I barely believe it, myself. Life elixirs and holy grails belong in fantasy novels and Indiana Jones movies. Any reasonably skeptical person confronting this extraordinary list of effects must have several questions screaming to the front of their mind, including but not limited to:

Are we sure GLP-1 drugs are this good?

How can one drug do everything?

If the drugs really do everything, why aren’t we all on it?

This post is my effort to answer all three questions.

But first, a word of caution. Some people think of Science, with a capital-“S”, as the official declaration of eternal truths. I prefer to think of science, with a lower-case “s”, as a messy scrabble toward half-truths that are often overturned with further research. I’m thrilled by studies that make GLP-1 therapies seem like holy water drawn from the fountain of youth. I’m also a realist who suspects that the final verdict on this medicine is many years away. So, please think of this as a first draft of history as we know it, rather than some kind of official announcement that GLP-1 drugs should be piped into the municipal water supply.

1. Are we sure GLP-1 drugs are this good?

As a fixture in news headlines, GLP-1 drugs are a recent phenomenon. As a subject of scientific study, however, the molecule is decades in the making.

Our story begins with a deep-sea monster. In the 1970s, a team of genetics researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital were studying animal hormones when they ran into a problem. The National Institutes of Health had banned some gene editing in warm-blooded animals on ethical grounds. So, the scientists went looking for cold-blooded animals instead. They settled on the anglerfish—which resembles the physical manifestation of a Tim Burton nightmare—because, as one scientist put it, they’re "a trash fish ... they’re ugly.” Tragically, no one at NIH was clamoring to protect this handsome fella:

Scrutinizing the poor beast, the scientists had a “eureka moment” when they discovered that anglerfish genes coded for several peptides related to the gut hormone glucagon. Scientists later identified that hormone as “glucagon-like peptide 1”—GLP-1. Further research showed that GLP-1 reduced blood sugar levels in mammals, making it a promising candidate for diabetes medication. The problem, however, was that the molecule’s half-life was much too short to serve as a useful medicine.

Enter the lizard. In the early 1990s, the scientist John Eng wanted to understand how the Gila monster, the stocky venomous reptile pictured below, could survive for several months between meals. When he studied the lizard’s venom, he discovered that its saliva contained a hormone called exendin-4, which worked much the same way as GLP-1, but lasted much longer.

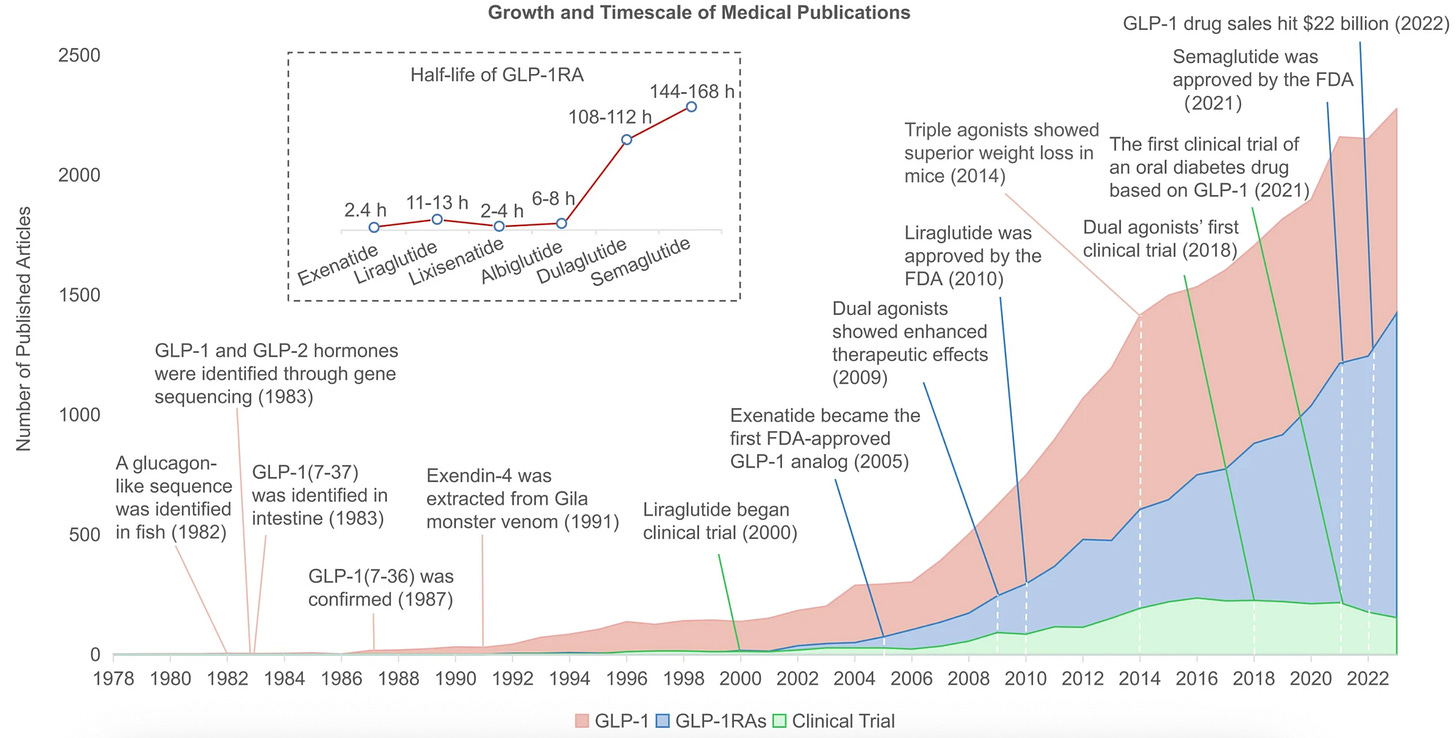

A drug based on that molecule, called Exenatide, became the first approved GLP-1 receptor agonist for treating diabetes in 2005. This breakthrough kicked off an arms race. In 2010, the Danish company Novo Nordisk received regulatory approval for their drug liraglutide. In 2017, the FDA approved another drug, semaglutide, which is the basis for Ozempic and Wegovy. As the chart below shows, the arms race is accelerating. In the last few years, scientists have found that targeting multiple gut-hormones leads to even greater weight loss.

The purpose of reviewing this history is to establish the point that these drugs have been with us for a long time. The first precursor to Ozempic and Mounjaro came out 20 years ago. This means we have a lot of evidence about both their effectiveness as well as their long-term risks.1

To finally arrive at a brisk answer to the above question: Yes, GLP-1 drugs seem like the real deal, even if the specifics of their broad benefits remain uncertain. We have lab, animal, clinical, and cohort data testifying to their broad effects. The most comprehensive analysis of GLP-1 drugs on a large population was published earlier this year. A team of scientists looked at more than 1 million patients with type 2 diabetes in the Veteran Affairs Medical System. They compared patients on GLP-1 drugs with those who been prescribed other meds. GLP-1 drug usage was associated with a reduced risk of … just about everything bad: “substance use and psychotic disorders, seizures, neuro-cognitive disorders (including Alzheimer’s disease and dementia), coagulation disorders [e.g., means clotting], cardio-metabolic disorders, infectious illnesses and several respiratory conditions.”

When I initially read this study in January, it seemed too good to be true. Miracle drugs don’t exist. Perhaps, I thought, there were nuances that I’d missed. So I called up a co-author of the study, the Washington University physician-scientist Ziyad Al-Aly. On my podcast Plain English, Al-Aly told me that GLP-1 drug use really was associated with improvements across every biological system they studied. “They're really remarkably beneficial, across multiple organ systems,” he said.

A single study should never be the final word on anything. Fortunately, the Veterans Affairs paper isn’t the only cohort analysis that testifies to the broad benefits of these drugs. Last year, a team of researchers at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine studied 1.6 million patients with type 2 diabetes and found that those on GLP-1 drugs had “significant risk reduction” of ten cancers: esophageal, colorectal, endometrial, gallbladder, kidney, liver, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer, as well as meningioma and multiple myeloma. “These drugs come out looking like superstars,” the Yale researcher F. Perry Wilson wrote. “As more data comes in, I become more convinced that we may look back on these drugs as the greatest medical breakthrough of the 21st century.”

2. How can one drug do everything?

Vaccines do one job well. They’re like a key designed perfectly to open one lock. GLP-1 drugs, however, seem more like a lanyard that holds your house keys, your car keys, your friend’s backup keys, your CVS rewards card, your work fob, and a mini Swiss army knife that has little tools on it that you’ve never actually figured out how to use. They do a zillion different things, and, like some of the tiny blades on that Swiss army knife, it’s not entirely clear how some of these things actually work.

Here’s what we think we know for sure: GLP-1 drugs stimulate the production of insulin (which reduces blood sugar) and suppress the release of glucagon (which tends to raise blood sugar). This makes it an ideal weapon against type 2 diabetes. We’re also pretty sure that the drugs work by slowing gastric emptying, which means that food stays in people’s stomachs for longer. Patients often feel full and rarely feel hungry. They frequently report less “food noise”—the constant worrying and planning around eating that’s reported by many people who struggle with their diet. With the combination of full stomachs and clear minds, calorie intake goes down, and weight follows.

But why should a drug that helps with insulin also help with memory? Why should a drug that makes you think less about food also reduce migraines and gambling compulsions and Parkinson’s symptoms?

This is where I think the best path forward is to present several theories, which I’m listing roughly from plausible to speculative. Again, we’re dealing with a lanyard here, not a single key, and I suspect that the magic of GLP-1 drugs is that they’re doing many things at once, some of which we won’t understand for many years.

Theory 1: The drugs work mostly because obesity and high blood sugar are really bad for you.

Maybe GLP-1 drugs seem to do everything because obesity (and high blood sugar) are broadly bad for you, and anything that reduces obesity (or high blood sugar) is broadly good for you.

“Obesity is actually a bad thing,” Al-Aly told me. “Obesity is a bad thing for your heart and for your liver and for lots of diseases.” Indeed, some of the benefits of GLP-1 drugs seem to be straightforwardly about weight loss. For example, obesity is associated with a higher risk of developing several cancers, including kidney and liver cancer. Anything that treats obesity ought to automatically reduce that cancer risk. Or, take sleep apnea. Heavier people have more fat around their throat and upper respiratory tract, which makes it harder for some of them to breathe when they’re lying down. Any intervention that burns fat around the throat—whether it’s a drug, bariatric surgery, or a diet—should automatically help many people’s sleep.

But the “obesity is bad, period” explanation just can’t explain everything that scientists are seeing. Most curiously, GLP-1 drugs often produce wonders among patients who aren’t diabetic and who barely lose any weight. Several large trials have found that the cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1s appear almost immediately, while weight loss takes time. One GLP-1 drug, known as albiglutide, which was withdrawn from the market with only a modest effect on weight loss, nonetheless “reduced the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events by 22%”.

These drugs are clearly pulling levers and pressing buttons in the body that have nothing to do with obesity or insulin. So, we need to look to less obvious mechanisms.

Theory 2: GLP-1 is a miraculous “moderation molecule,” and it has docking portals all throughout the body that reduce inflammation.

Perhaps the secret to GLP-1 drugs’ success might be hidden right there in the name. Remember when I said earlier that the drugs are technically known as “glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists”? Well, we’ve talked a lot about the GLP-1 part of the name, which refers to the special hormone that these drugs mimic. But the receptor agonist piece is crucial. Receptors are tiny proteins on cells that bind to outside molecules. You can think of them like a lock outside a door. An agonist is a molecule that activates the receptor. You can think of it like a key.

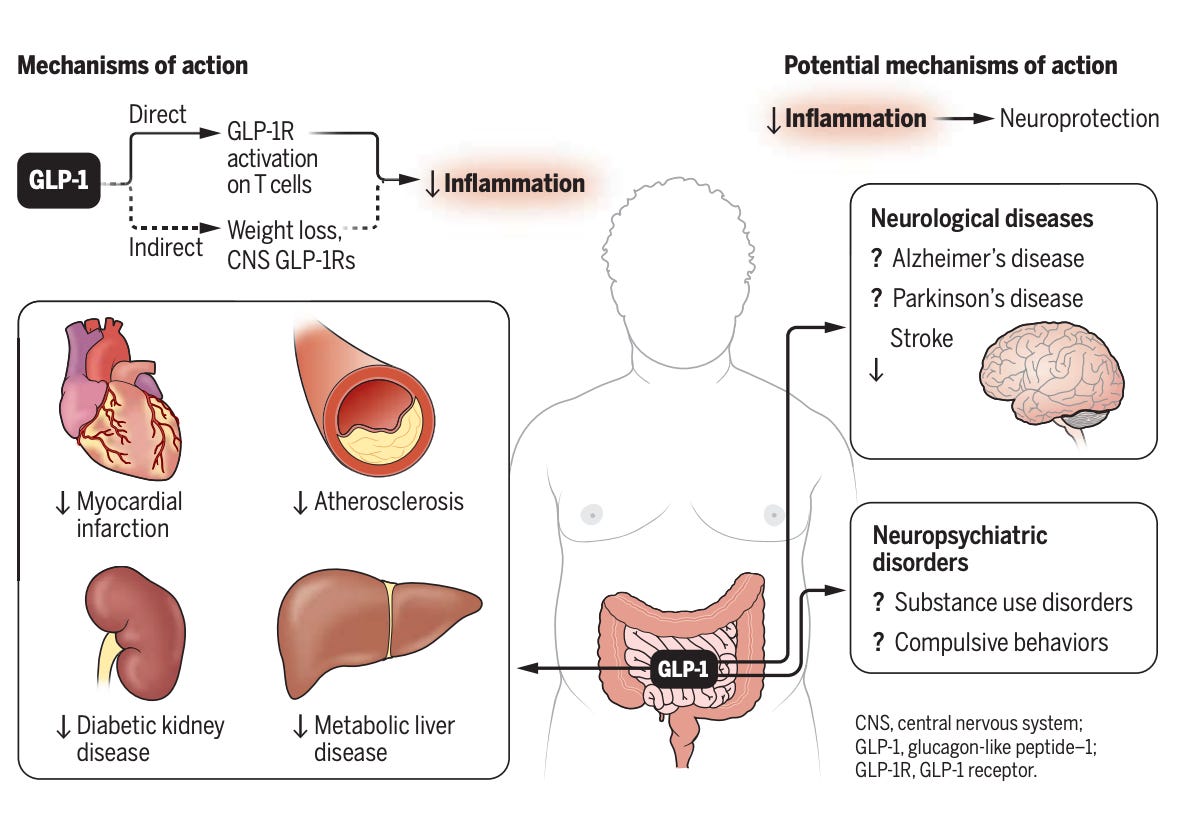

In a surprise to the drugs’ developers, a dizzying number of our organs and tissues seem to have GLP-1 receptors (locks) that are ready to bind to these chemical agonists (keys). In our kidneys, GLP-1 activation seems to reduce local inflammation and improve renal function. Around our hearts, GLP-1s bind to receptors in cells lining our arteries, kicking off “a signaling cascade” that keeps blood flowing and reduces the risk of plaque accumulation and strokes. (GLP-1 receptors also seem to be strewn throughout our immune cells and neurons, although we’ll get to that a bit later.)

The Canadian scientist Daniel Drucker has done more than practically anyone in the world to illuminate the benefits of GLP-1 drugs. In a recent essay in Science, he proposed that a "unifying" mechanism of these drugs could be the calming of bad inflammation. When our bodies notice germs or tissue damage, our immune response brings immune cells to the area. (Think about how your knee feels warm when you bang it; that’s normal inflammation.) But excessive chronic inflammation, which results from an immune system over-policing threats throughout the body, is a leading cause of organ damage, stroke, and neurological problems. GLP-1 drugs seem to bind to receptors throughout the body—in our gut, on our immune cells, and throughout the central nervous system—to broadcast the same message: STOP THE ATTACK! LESS INFLAMMATION, PLEASE! Drucker provides this illustration of the mechanism:

Scientists still aren’t quite sure how these drugs effectively moderate every system that they touch. They reduce over-eating as efficiently as they reduce inflammation. Like a some itinerant Buddhist monk, they travel throughout the body preaching a message of moderation everywhere they visit. As we’re about to see, their powers of moderation are genuinely transcendent in the realm of cognition.

Theory 3: It’s a brain drug.

I think the most mysterious thing about these drugs is their effect on the brain. One analysis of several hundred GLP-1 studies presented compelling evidence that they improve cognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, substance-use disorders, such as alcohol, cocaine, and cannabis addiction, and mood and anxiety disorders, such as depression and bipolar disorder. These findings point to a central mechanism—beyond weight loss and blood sugar control—where GLP‑1 medicines are acting directly on the brain to support cognition, mood, and neural health.

Scientists barely understand the brain, and they barely understand GLP-1 drugs, so explaining GLP-1 drug function in the brain is a bit like translating a conversation conducted in two different languages you’re only semi-fluent in. But from my read of the literature, GLP‑1 drugs act on the brain in two ways. First, neurons throughout the central nervous system have GLP‑1 receptors, too. Activating these receptors protects nerve cells from damage and calms inflammation in the brain, just as they do throughout the body. Rather than slowly cook in the hot water of chronic inflammation, brains on GLP-1 drugs bathe in the cooler climates at which they excel at cognitive functioning. I guess you can think of this as an extension of our “moderation molecule” hypothesis.

Second, several experiments — whether they involve slices of brain tissue, animals, and even human volunteers — have strongly suggested that GLP-1 drugs specifically act on our dopamine cycles and affect neural activity in the hypothalamus, the appetite-controlling region of the brain. By acting as dopamine thermostats, they allow people to “turn down the volume” of their cravings and distractions.

If GLP-1s are suppressing the release of unwanted dopamine firings, the implications could be immense. Dopamine is critical to focus, motivation, and goal-setting. Could a modified version of these drugs ultimately serve to help people with attention disorders? I guess it’s possible. In fact, one clinical study of obese patients published in Nature Metabolism in 2023 found that those treated with liraglutide saw significant improvement in a range of “associative learning tasks” versus the placebo group.

As exciting as the effects of GLP-1 drugs are on cancer and heart health, don’t sleep on the possibility that pharma companies will eventually test versions of these drugs that are explicitly focused on improving cognitive function.

A summary judgment: GLP-1s as pinball wizard drug

Imagine a pinball machine. When you launch a ball, it pings around the board’s targets and bumpers and pockets, racking up points as it flies around. The human body is a machine with many welcoming targets for GLP-1. The drugs dock with receptors in our gut, near our heart, in our immune system, and in our brain. We seem to have discovered in the bowels of some of nature's strangest creatures a molecule that scores points throughout the mammalian body by moderating the activity of all sorts of systems. The end result is a broad-based reduction in inflammation, a calmed central nervous system, and a reduction in craving that gives people the ability to ignore unwanted cravings and focus on what they want to pay attention to.

3. So, should we all be on GLP-1s?

No. Certainly not now. While I’m excited about the future of these drugs’ development, the side effect profile isn’t worth the risk for otherwise healthy patients. The anti-inflammation and cognitive benefits of the drugs still come with weight-loss effects that many Americans shouldn’t accept.

In fact, this is a good time to pour a bit of cold water on the GLP-1 revolution that I’ve probably spent a bit too much time inadvertently hyping up. You wouldn’t know it from the most cheerleading business coverage of GLP-1s, but the drugs’ revenue growth has actually come in below market expectations in the last few years. Google search volumes for the drugs in the U.S. have flattened in the last few months. One major problem is adherence. A majority of people prescribed GLP-1 drugs stop using it within the first year. Maybe it’s the side effects. Maybe they miss drinking and don’t appreciate the nausea. Maybe they can’t afford the drugs. Maybe they stop after they hit their target weight. Maybe people just don’t like injectables.

Despite these challenges, many analysts project that the GLP-1 market is on the cusp of its biggest breakout. “We are now at an inflection point for ‘The Broadening’ of GLP-1 use, which will extend beyond US-based early adopters to date, to larger numbers of patients globally,” Morgan Stanley analysts wrote this year. The bank’s enthusiasm is based on several factors. As GLP-1 supply grows and insurance coverage expands, prices should drop. As companies develop stronger oral meds that are more convenient and more potent, their reach should expand.

But the most interesting driver of GLP-1 drugs’ long-term popularity might be exactly what we’ve spent much of this article discussing: their vast clinical benefit. Today’s GLP-1 drugs do a hundred different things, and we barely understand how or why. But as scientists and drug developers isolate the mechanisms behind their anti-cancer, anti-dementia, and anti-inflammatory effects, we might get specially tailored drugs for cancer, dementia, and inflammation. There are several ongoing trials attempting to lock down the drug’s effects on Alzheimer’s. If these experiments pan out, we could see clinical trials of drugs specifically tested to protect memory among older people.

A decade from now, the most popular GLP-1 drugs might advertise weight loss as a secondary benefit. We could have long-lasting GLP-1 pills for brain health, for heart health, for renal health, and beyond.

As with all things in biotech, the future is profoundly uncertain, and progress will always have roadblocks. For example, the push for more oral medication will not be simple. Elizabeth Cairns, a reporter at Endpoints News, pointed out that while pills would likely increase adherence, oral drugs are often dosed at higher levels than injections, which means they often come with more side effects. “Pfizer recently had to abandon its GLP-1 pill based on safety concerns,” she writes.

Sometimes, our inventions turn out to be our best science experiments. One of my favorite pieces of tech history is that the men who built the first steam engines didn’t actually understand how their machines worked. The laws of thermodynamics—such as the conservation of energy and the law of entropy—didn’t exist when Newcomen and Watt completed their first engines. Decades after these inventions, other scientists studying the devices in the 1800s developed the laws of thermodynamics, from which physicists have derived truths that explain the workings of the entire cosmos.

If the steam engine was the little machine that accidentally explained the universe, the GLP-1 hormone may one day be regarded as the peptide that accidentally decoded the body, the mind, and basis of human health. Alexis de Tocqueville, describing the conditions of the early industrial revolution as it swept through 1830s Manchester, once wrote: “From this foul drain, the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the whole world; from this filthy sewer, pure gold flows.” We will be lucky if, one day, one might say that from the foul throat of the Gila monster and the filthy sewer of an anglerfish gut flowed one of nature’s most miraculous molecules.

The most common side effects of GLP-1 drugs are well known but important to list, particularly nausea, acid reflux, pancreatitis, and light headedness. There have also been studies suggesting a slightly elevated risk of thyroid C-cell tumors.

Great article. In my reading of the biomed literature, these drugs spoof the same pathways that the microbiome uses to tell the body that it is sated (namely the production of short chain fatty acids SCFA from soluble fiber in the colon). In that sense, besides the effects of obesity, these drugs offset many of the deleterious effects of not eating a predominantly plant based, high fiber diet (and having a microbiome to match).

Not to go 'paleo' but it is clear that while early humans ate meat, it is clear from fossil evidence (e.g. fossilized human poop) that early humans often ate up to 50-100 grams of fiber a day, indicating a plant based diet. The genetic differences between us and the great apes are all adaptations for eating large amounts of starch, not animal protein. The greatest early invention might not have been the spear, but rather the digging stick for accessing deep tubers. Fire might have been a way to make those tubers edible, rather than a prehistoric BBQ.

There is plenty of evidence that the meat heavy western diet is bad for us. GLP-1 drugs are amazing because the spoof our Western-diet fed bodies into thinking we are eating vegan.

I love these fast deep dives, like Scott Alexander for people who don’t want to read the actual papers.