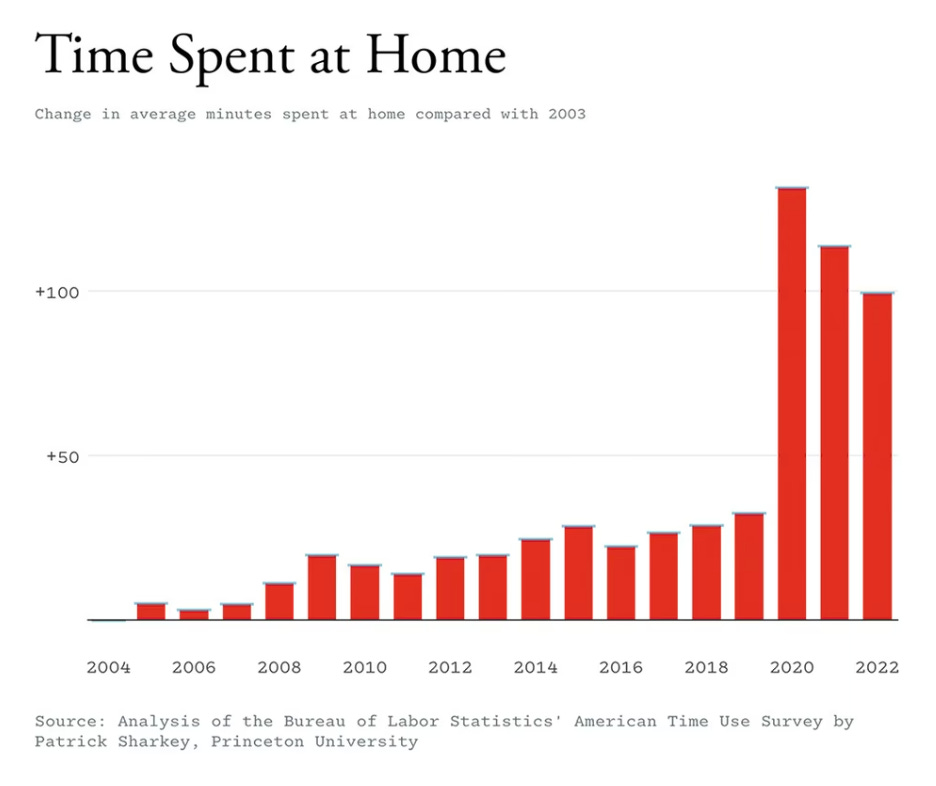

Americans are more alone than ever. Face-to-face socializing has plummeted this century, especially for young people. Nobody parties anymore. We spend more time in our homes than any period on record. The graphical evidence is dire.

The causes for this social collapse are complex and diverse. But one of them might be a fundamental bias at the heart of the so-called social animal: a deep social anxiety about our ability to get along with, or be interesting to, new people. In the last few decades, several studies have found that Americans underestimate how much they’ll enjoy conversations with strangers, perhaps out of a fear that we'll bore others or find nothing in common with them. One of the most famous studies in this space was led by Nick Epley, a psychologist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

Several years ago, Epley asked commuter-train passengers to predict how they’d feel if forced to talk with a stranger…

Most participants predicted that quiet solitude would make for a better commute than having a long chat with someone they didn’t know. Then Epley’s team created an experiment in which some people were asked to keep to themselves, while others were instructed to talk with a stranger (“The longer the conversation, the better,” participants were told). Afterward, people filled out a questionnaire. How did they feel? Despite the broad assumption that the best commute is a silent one, the people instructed to talk with strangers actually reported feeling significantly more positive than those who’d kept to themselves. “A fundamental paradox at the core of human life is that we are highly social and made better in every way by being around people,” Epley said. “And yet over and over, we have opportunities to connect that we don’t take, or even actively reject, and it is a terrible mistake.”

I think this is one of the most profound ideas in modern social science: People routinely deny themselves the pleasure of social experiences because of an anxiety that’s based on a delusion: the delusion that we are boring and that we’ll find others boring, too. Today, we’re talking about this and much more with one of my favorite psychologist-writers, Adam Mastroianni. We talk the psychological underpinnings of social anxiety and why great conversations have lots of “doorknobs.” I’ve made a transcript of the interview’s highlights, which is very lightly edited and condensed for clarity below.

On why most people are too pessimistic about their ability to be interesting and make friends

Derek Thompson: People tend to be very optimistic and about their own abilities. We think we’re better drivers, cooks, readers, and sleepers than we actually are. But in the realm of talking to other people, you've argued that we're actually too pessimistic. Why?

Adam Mastroianni: In a bunch of different studies, some that I've done myself, if you ask people like, “hey, in the next room over, there's a stranger in there, you’re going to go in there and talk to them, how do you think that's going to go?” Even as I say that, I can feel myself cringing inwardly. I think: They're not going to like me, I'm not going to like them, it’s going to be bad. But now we've done tons of studies where we do exactly this. We put people in the room with a stranger. They talk. And when they come out, we're like, how was that? And they're like, oh, it was great.

Thompson: Why is that significant?

Mastroianni: Well, for one thing, every person that you ever met was once a stranger to you. Sometimes you didn't really have a choice in the matter because they were caring for you as a baby. But everyone you now know and love, you had to get to know them and especially your closest friends. At one point, they were the stranger in the next room over. And if you had chosen to walk by the door rather than open it and go in there, they wouldn't be your friend. And so clearly there's something holding us back from going through that door. And I think we pay the price for it.

Thompson: To what extent is this the basis of modern social anxiety and social anxiety disorders? This presumption that we might be boring to other people and we want to spare them the unfortunate experience of exposure to us?

Mastroianni: I think that's part of it. But I'm not sure how much. It’s not just that people think that the other person is going to find me boring. It's that I don't think we're going to have things in common. I don't think they're going to like me. One thing we found watching back videos of people in conversation is the way my co-author described them as “similarity-seeking missiles.” The very first thing that people do when they encounter someone else is try to figure out “how are we similar?” and “can I locate you in my social graph?” I think part of it is the fear that whatever I’m interested in, you're not going to be interested in it.

Thompson: It's funny because it's not that we're bad at conversations. It's that we're bad at thinking we're bad at conversations. This is a theme that comes up in your work a lot. Most people are okay at talking. And if they just got over that a little bit, they would expose themselves to more current strangers who would be future friends. There’s broader academic literature that says lots of people are afraid of having conversations with strangers and in particular afraid of having deep conversations with strangers. I'd love for you to represent at a higher level what this research is telling us.

Mastroianni: It seems like the takeaway from this research has been done over the past 10 years or so is that people are way too negative about their own social abilities and the things that are likely to happen when they talk, especially to someone new. So, for instance, they underestimate how pleasant it's going to be to talk to someone new. But even afterward, when we ask them, hey, how much did you like that person? They say oh, I like them a lot. And when we ask, how much did they like you? Oh, less than that. I ran one study with some friends of mine where we had people talking groups of three and we're like, okay, how much did you like them? People would say 5 or 6 out of 7. And how much did they like you? People would say 4 or 5 out of 7. On average, people thought they were the least liked person in the conversation, which obviously can't be true for each person.

Thompson: We are, on the one hand, the social animal. Yet we delude ourselves about the degree to which we're a fun hang. We're the social species and we're the socially anxious species as well.

Mastroianni: Yeah, well, we're the ones who care about it the most. And so we have the most to lose. And so we worry about it the most in part in the hopes that maybe it makes us better at doing it. The way I think about it is in our evolutionary history, we lived in groups. But how often did we meet someone who we literally had no connection to before? I can't imagine it was all that often. But today it can happen literally every day. You get on the bus and it's full of people that aren't related to you. You don't know them. They don't know you. That's a really weird thing to do.

There's another problem, which is that strangers are this group of people that you can never learn anything about because as soon as you learn anything about a person, they stop being a stranger. And so there's this weird thing where people keep meeting new people over the course of their lives and go like, oh, that person wasn't a scary stranger. That was just like a friend in waiting. So the next person is going to be the scary stranger. Each time, it feels like it's the exception to the rule. What we never learn is that most people that you meet are totally fine. There's very few villains in the world.

On the Anti-Social Century and Loneliness

Thompson: In the story that I wrote earlier this year, The Anti-social Century, one of the themes that I was trying to unspool is this idea that we're often told by the media that we have a loneliness crisis. But I don't like the idea of a loneliness crisis. I think that loneliness can be usefully understood as a biological cue that tells us that there's a gap between our felt level of social connection and our desired level of social connection. So when I’m lonely, I want to hang out with someone. I want to cure this loneliness with the medicine of other people.

And it seems to me like that biological instinct to cure our solitude with other people is being overridden in the age of ample entertainment, and especially phone-based entertainment. Loneliness is the wrong word there. It's a phenomenon of solitude and highly sought solitude rather than a crisis of people feeling lonely and wanting to be around other people all the time. To what extent does that interpretation click into this research you’ve described?

Mastroianni: Yeah it totally makes sense. I have some friends who are working on a new paradigm for psychology, thinking about it in cybernetic terms, where the mind is a stack of these control systems that's meant to keep a bunch of important variables at the right level. Hunger is an obvious one. When you don't have enough nutrition, you get hungry and then you eat and then that signal goes down and you stop eating. Loneliness is just social hunger. You feel this signal. It makes you want to do certain things. You go out, you do them and the signal goes away.

The thing is that signal didn't evolve in an environment where you could, instead of, you know, walking next door and talking to someone, you could look at a glowing square of glass. So some of that signal goes away. But not really. It's a little bit like you're hungry, but you're eating the little potato chips that are left at the bottom of the bag.

On why great conversations have ‘doorknobs’

Thompson: Your most popular essay ever is about how the best conversations have “doorknobs.” I beg everyone who hasn't read that essay to do so. What’s the essay about?

Mastroianni: While I was working on this research on whether conversations end when people want them to, I was also doing a lot of improv at the time. And there is this technique in improv called “take and take” rather than “give and take.” So I was in a musical improv group at the time. And when you're improvising a song on stage, you're making up the lyrics on the fly. It’s hard. You could maybe do a line at a time. As soon as you start singing, you want it to stop it as soon as possible because you've got one rhyme in your head. You need someone else to take over. The way to solve this problem is for the next person who has an idea to take the focus from you, to step in front of you, to start singing because you don't know which of the other six people or whoever on stage has the next idea.

This is one model of having a conversation. I think it's an underrated model. A lot of people think, especially people who are like very derogative about conversations, they think that conversations unfold as a series of invitations: I talk and then I ask you a question and you talk and you ask me a question. But another model is: I talk, and I may create an opportunity for you to talk next that you could take or not take, and I could do the next one.

I think of these two modes as giving versus taking. And a lot of people think that the only way to be a good conversationalist is to constantly be giving, by inviting you to participate in the conversation. Whereas there is a caring way of having a conversation that is in fact taking. I create an opportunity for you to respond, even if I don't necessarily use a question mark. If I say something that you can respond to, then I've created what I think of as a doorknob, an affordance, a way for you to open the door to the next part of the conversation.

Thompson: Give me an example. What's a good conversation doorknob, and what's like a door where the doorknob wasn't installed?

Mastroianni: A lot of people think that any question is inherently a polite thing in a conversation. But some questions are really dead ends. Like one that comes up weirdly often in introductory conversations is, “So, got any siblings?” People are like: Yes. One. And it's like … Alright? It's not clear what to say to that. As opposed to, “are you close with your family?”, or “did you look up your older sister?” Not every question is made equal. Some invite people's participation and some preclude it.

Similarly, not every statement is made equal. I mean, a statement like, “Yeah, I have one sister” doesn't invite the other side to be like, “I also have one.” Versus “I have a sister, and here's what we talk about all the time, here's an argument that we have all the time, here's a difference of philosophy that we have that comes up all the time, here's actually how we've grown closer through having that disagreement.” Now there's a ton of source material for the other person to respond to. But it's also up to them to grasp the doorknob

Thompson: What are the keys to being a doorknobby talker?

Mastroianni: To go back to improv, so many improv scenes fail because we blow past all these interesting details and we keep looking for the next interesting thing. But interesting and weird things are happening all the time in conversation, and at any point you can just be like, that was interesting and weird! When people ask me what I do, I’m like “I write a blog and I’m writing a book. And sometimes people are like, “Oh okay. Pretty hot today, huh?” What I just told you is actually pretty weird! I write a blog! When I meet people who are like, yeah, you know, I research the history of cloths, I’m like, what?! Where did that come from? How did that start?

Thompson: I do think that “that sounds weird” and “that sounds hard” are underratedly simple ways of being doorknobby. I was talking to some other psychologist and he told me that “that sounds hard” are the most magical three words in any conversation, because you're inviting the other person to disclose something that is intimate at the suggestion that their lives are difficult. And, if the rise in psychotherapy in America is a sign of anything, it's that people love talking to other people about the degree to which their lives feel difficult to them.

I think the first time you and I spoke, you had just written about the field of psychology. You said that to the extent that there are any grand truths that psychologists have uncovered, one of those grand truths is about the discrepancy between how we think our mind works and how our mind actually works. What would you say is the grand truth of all this research on conversations?

Mastroianni: I would say that the world inside a conversation is completely different and opaque to the world outside the conversation. And this shows up both in how people make all the wrong predictions about what's going to happen inside of it, but it also shows up in what they look like to other people versus what they feel like to be in. They're watching these conversations back and going, these people look like they're having a horrible time.

It’s really hard to tell what this conversation feels like on the inside, in part because it's about you. We don't think about that when we're about to talk to someone else. We think we're going to be talking about the weather or sports. Actually, we're going to be talking about us. And it turns out to be way more interesting and risky and challenging and cool than people think it will be.

Thank you Christopher Hale, Charles Duhigg, Taryn Arnold, Juan Salas-Romer, PinkTaffy Thoughts, and many others for tuning into my live video with Adam Mastroianni! Join me for my next live video in the app.