The Sunday Morning Post: Whatever Happened to Serial Killers?

One of my favorite social mysteries is deeply relevant in 2025.

Welcome back to The Sunday Morning Post, this newsletter’s weekly digest of discoveries and developments that violate the rules of the news cycle. The goal of TSMP is to ignore the vast majority of stories that are sudden and negative and to highlight those that are slower-moving, often positive, and more consequential—stories, in other words, that are likely to be as relevant in 10 years as in 10 hours.

Today, we’re talking about one of my favorite and most gruesome sociological mysteries of the last 100 years—and why I think it’s especially relevant for an under-reported story in 2025.

My favorite movie is The Silence of the Lambs. Close behind is David Fincher’s film Se7en. I think the best film of the 21st century is No Country For Old Men, and somewhere in the top 10, I’d have to include Fincher’s Zodiac, as well.

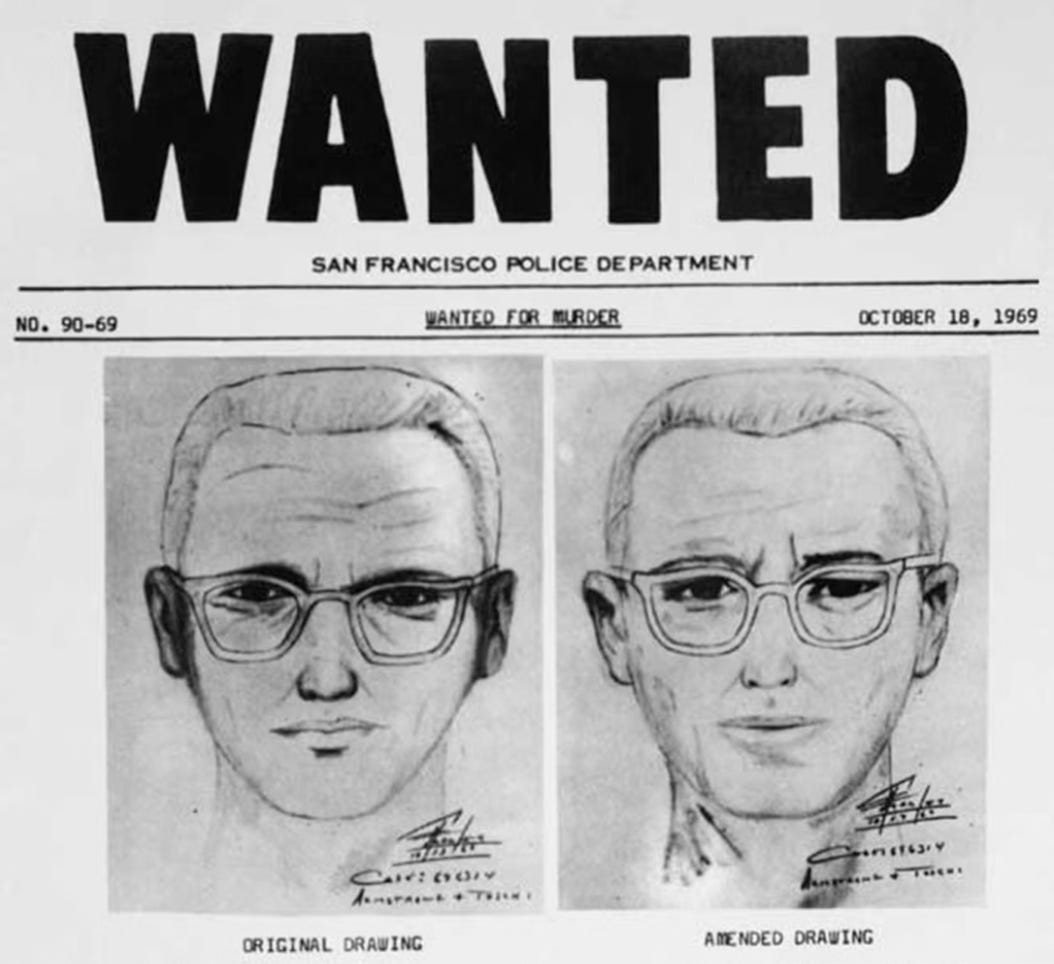

Beyond exceptional cinematography, the thing that unites all of these films is they’re all about serial killers and repeat murderers and generally bloody mayhem.1 Another thing these films have in common is that they were all made in, or take place in, the years between 1965 and 1995. In fact, most of the real-life serial killers that still have name recognition—including Zodiac, Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, the Golden State Killer, BTK, and Son of Sam—were active in that same period, between 1965 and 1995.

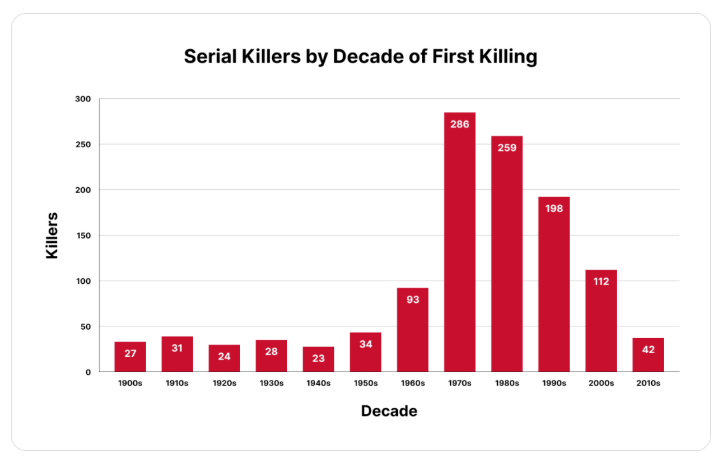

As an archetype, the serial killer seems like a classic fixture of American life. But as an actual phenomenon, it’s much more faddish than you’d think. According to the Radford University Serial Killer Database, the number of serial killers in the U.S. increased by a factor of 10 between the 1940s and the 1970s. Just as quickly as it emerged, it dissipated. By the 2010s, the number of serial killers had crashed 80 percent from its peak. The result is the following strange and bloody bulge:

What happened to the American serial killer? James Alan Fox, the Littman Family Professor of Criminology, Law, and Public policy at Northeastern University gave me five answers:

The 1960s-1990s period had more violence in general .. possibly because of the baby boom. Homicides spiked between the 1970s and 1990s, and so some of the serial killer phenomenon was likely a reflection of this broader increase in lethal violence. Fox told me that while he generally disfavored the lead hypothesis for the crime wave—which blames the rise of criminal behavior on lead exposure among young people—he was more influenced by the “youth bulge” theory that large generations, such as the baby boom, are associated with an increase in crime as that generation passes through their teenage years. Several international studies have found an association between large youth cohorts and political violence, even in “highly democratic countries.” In fact, the homicide rate went down as the baby boomers aged out of their most crime-prone years.

Americans were more socially trusting before the 2000s, which at the extremes created more opportunities for psychopaths. After World War II, the U.S. was coming out of the high-trust 1940s and 1950s, and the 1960s and 1970s were marked with significantly less “stranger danger.” The country had a high number of runaways, hitchhikers, and latchkey parents whose children appreciated the freedom offered by their folks. “You add to that the sexual revolution and the changes in sexual mores,” Fox told me, and it’s a generation where “people weren't afraid of strangers.” All this offered more grisly opportunities for sickos.

A technological revolution in information sharing after the 1980s made it harder to get away with itinerant violence. Serial killers rarely stuck to the same neighborhood, or town. They would often travel, kill, and travel again, or they would avoid attacking the same neighborhood too many times, to avoid getting caught. In the 1960s and 1970s, information-sharing across departments was onerous. Police record-keeping was paper-based, cooperation was grudging at best, and evidence was siloed between jurisdictions. Even until the 1980s, few local departments had computers that allowed them to share information on records management systems. It was only in the 1990s that large-scale fingerprint identification and national incident reporting systems were developed. With the rise of computerized databases, “it’s much, much easier for police to communicate in today’s world,” Fox said.

A technological revolution in forensics made it harder to get away with intimate violence. You may have seen reports that more and more murderers are getting away with their crimes. It’s true the murder “clearance rate”—the share of killings that end in an arrest, or get solved—has steadily declined over time. This is largely because today’s violence is increasingly gun-related (and gun evidence can be hard to trace) and gang-related (gang members are hard to turn). Serial killing, by contrast, tends to be very up close, personal, and even sexual in nature. That means serial killers have historically left behind a lot of DNA evidence. For decades, this didn’t make them vulnerable to capture; DNA wasn’t used for forensic purposes until the 1980s. But the DNA revolution of the last 40 years has turned the tiniest bit of blood, saliva, or hair into a jackpot for detectives and prosecutors. “It's very hard for someone now to commit sexual crimes in particular, where there’s lots of physical evidence, because of the contact with the victim,” Fox said.

Never count out TV and the Internet. Also, porn. I believe that every social phenomenon is, in part, a communications technology phenomenon. The age of the serial killer took off just after the rapid growth of television. TV news might have unwittingly played the role of social contagion amplifier, as psychopaths were encouraged by the success, and even inspired by the details, of other sickos whose dark accomplishments received lurid TV coverage. Even more importantly, Fox told me, the availability of pornography on VHS, then DVD, then Internet, and then smartphones has created more (and less violent) outlets for sexual sadism. “The growth of digital porn” he said, allows people to “satisfy their urges in ways that don’t involve murdering lots of people”—which has to be among the least pleasant yet consequentially positive things anybody has said to me in a reporting call.

One way to read these explanations is that, like five legs holding up a table, they collectively support and fully account for the rise and fall of the 20th century serial killer. But an equally valid, and perhaps even superior, implication is that crime waves and crime declines are both so mysterious that we have to draw on explanations that span demographics, technology, biotech, and entertainment to account for them. James Alan Fox has written dozens of books about criminology, and even he’s not fully certain that he understands the social and technological developments contributed most critically to the serial killer phenomenon. That’s something to keep in mind as we turn our attention to a more recent crime mystery.

Murder rates are plummeting in America

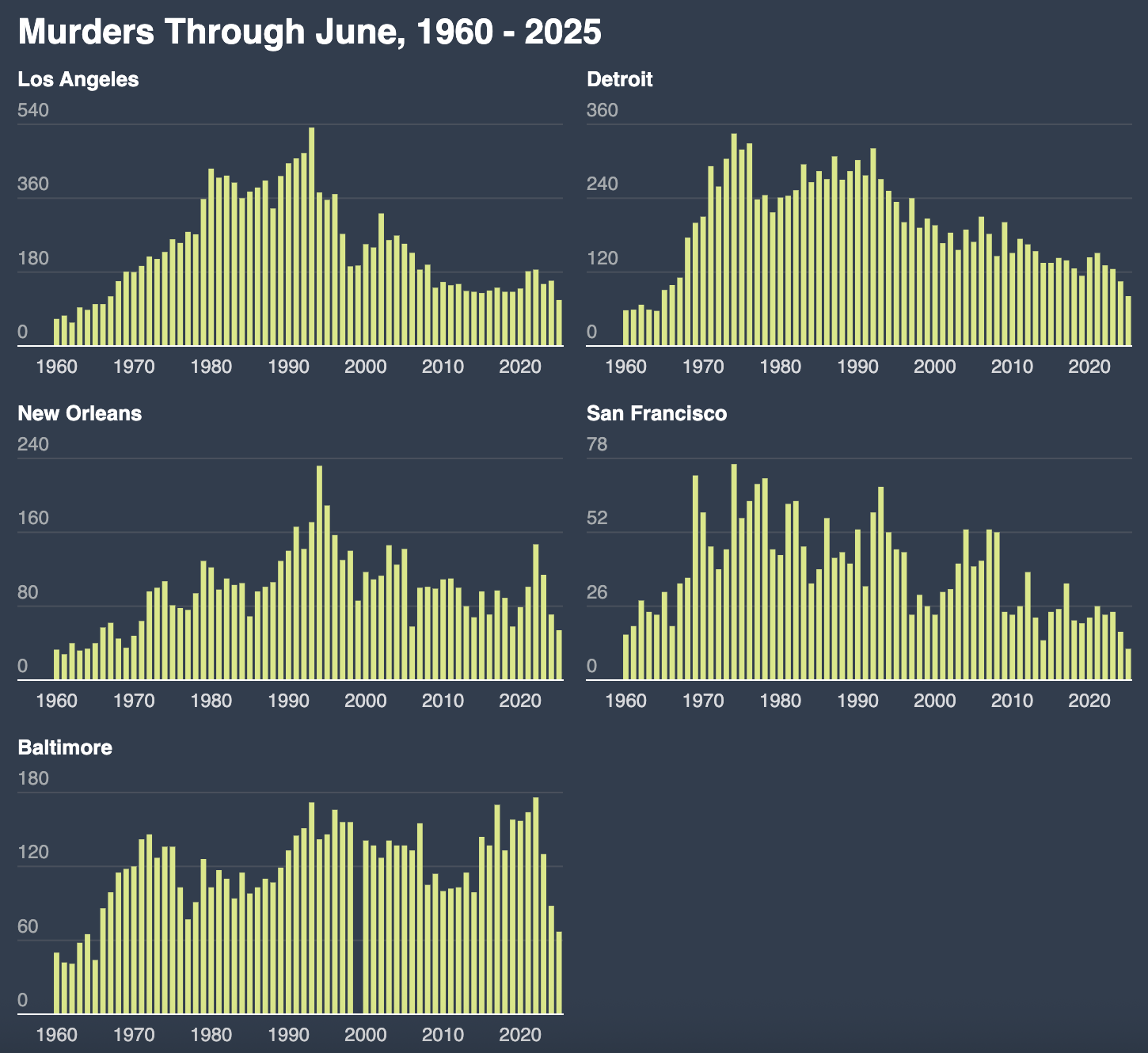

Murder rose at its fastest rate ever in 2020. In 2025, it seems to be falling at its fastest rate ever. While the fidelity of crime statistics is often debated, the crime analyst Jeff Asher has written that almost every major data source—including the FBI, the Real-Time Crime Index, and the CDC WONDER database—converges on the same finding: Crime is plummeting at historic rates, and in many cities, the number of murders is approaching record lows.

"Nobody knows for sure exactly why murder is falling so fast right now," Asher writes. Maybe 2020 was a uniquely chaotic year that created unusual conditions for a brief crime wave that was always going to dissipate. Maybe the decline in police activity allowed more violent criminals to flourish, and the post-COVID resurgence of policing and normal activities since 2022 have caused crime to fall back to its historically low levels. Asher continues:

When I think about the main factors behind declining murder, a strong investment in communities from private and public sources after the shock of the pandemic stands out as a major cause. There is a wide array of types of support that I would put into the “community investment” basket, including jobs, infrastructure, and programming, but it could be summed up as “we spent a lot of money everywhere on stuff.”

Overall, this is the explanation that I find most satisfying in light of the preconditions discussed above. And I’m not alone in this line of thinking.

John Roman has argued that local government returning to normal was essential for enabling government services to assist citizens. Roman also points to research showing a clear causal effect between nonprofit organizations working in communities and decreasing crime.

I see two points of resonance between the rise and fall of the serial killer and the rise and fall of 2020s crime. First, Fox and Asher both seem to be articulating versions of what has sometimes been called the guardian theory, or the “routine activity theory” of crime. This theory proposes that crime requires a likely offender, a suitable target, and (most importantly here) the absence of a guardian—meaning, a person or system that deters offenses, sometimes by just being present where they would otherwise take place. According to Fox, the absence of stranger danger in the 1970s meant more young people put themselves in vulnerable and isolated situations, while the absence of interstate cooperation by police departments and detectives meant there was no effective national guardian on behalf of serial-killer victims that spanned jurisdictions. According to Asher, the pandemic created the conditions of less policing and less local government presence. As civic guardians returned to the streets, crime plummeted back to its historic lows.

Another point of resonance between these stories is that social phenomena often create the conditions for their own reversal. The rise of serial killers and the rise of 1970s violence helped turn American society against the trusting of strangers2, which led to the demise of both serial killers and overall crime. Police violence in America in the 2010s and 2020 created a movement to protect victims, which became in part a movement to defund policing, which contributed to a decline in police presence, which may have helped crime rise, which created a new set of conditions in which police presence was welcomed back on the streets.

Technology and science often produce trends that look like straight lines. Computer chips just get cheaper. Cancer medicine just gets better. Culture sometimes moves in straight lines, too. (Just look at the 70-year fertility rate.) But unlike science, culture often denies us the affordance of straight lines. The shape of culture is often sinusoidal. Up and down and up and down. Culture is backlash.

At the psychological level, I’m not sure what this preference says about me, but as a wise man once said, I’ll outsource that question to my therapist.

I would argue we’ve probably gone too far in the other direction! But that’s the subject of another essay.

"Culture is backlash." This is such an important idea, and one that is too frequently ignored or rejected by people who want to legislate (or talk about) culture rather than the social circumstances that impact culture. In particular, economic insecurity causes, or at least contribute to, a broad range of negative cultural features, yet so many politicians prefer to focus on those features rather than economic issues. This focus is easier and it is emotionally much more appealing to voters, thus we are consumed by culture wars. You cannot make effective policy that targets culture, but you can study culture for insights into potential policy changes that could achieve positive cultural results. Of course, you would need a government interested in policy for that to occur.

So mad you didn’t talk about lead poisoning because I’m reading Murderland rn and that seems like the kinda theory you’d like