The Evidence That AI Is Destroying Jobs For Young People Just Got Stronger

A big nerd debate with bigger implications for the future of work, technology, and the economy

In a moment with many important economic questions and fears, I continue to find this among the more interesting mysteries about the US economy in the long run: Is artificial intelligence already taking jobs from young people?

If you’ve been casually following the debate over AI and its effect on young graduates’ employment, you could be excused for thinking that the answer to that question is “possibly,” or “definitely yes,” or “almost certainly no.” Confusing! Let’s review:

Possibly! In April, I published an essay in The Atlantic that raised the possibility that weak hiring among young college graduates might indicate an AI disruption. My observation started with an objective fact: The New York Federal Reserve found that work opportunities for recent college graduates had “deteriorated noticeably” in the previous few months. Among several explanations, including tight monetary policy and general Trumpy chaos, I considered the explanation that companies might be using ChatGPT to do the work they’d historically relied on from young college grads. As David Deming, an economist and the dean of undergraduate studies at Harvard University, told me: “When you think from first principles about what generative AI can do, and what jobs it can replace, it’s the kind of things that young college grads have done” in white-collar firms.

Definitely yes! Soon after my essay went up, several other major news organizations and AI luminaries endorsed even stronger versions of my hedged claim. The New York Times said that for some recent graduates “the A.I. job apocalypse may already be here.” Axios reported that “AI is keeping recent college grads out of work.” In a much-discussed interview predicting a labor “bloodbath,” Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei made the audacious forecast that AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs within the next five years. By June, the narrative that AI was on the verge of obliterating the college-grad workforce was in full bloom. Until …

Almost certainly no!: As AI panic reached its fever pitch, several whip-smart analysts called the whole premise into question. A report from the Economic Innovation Group took several cuts of government data and found “little evidence of AI’s impact on unemployment,” and even less evidence that “AI-exposed workers [were] retreating to occupations with less exposure.” In fact, they pointed out that “the vast majority of firms report that AI had no net impact on their employment.” John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times pointed out that “the much-discussed contraction in entry-level tech hiring appears to have reversed in recent months.” The economic commentator Noah Smith synthesized even more research on this question to reach the conclusion that “the preponderance of evidence seems to be very strongly against the notion that AI is killing jobs for new college graduates, or for tech workers, or for…well, anyone, really.”

To be honest with you, I considered this debate well and truly settled. No, I’d come to think, AI is probably not wrecking employment for young people. But now, I’m thinking about changing my mind again.

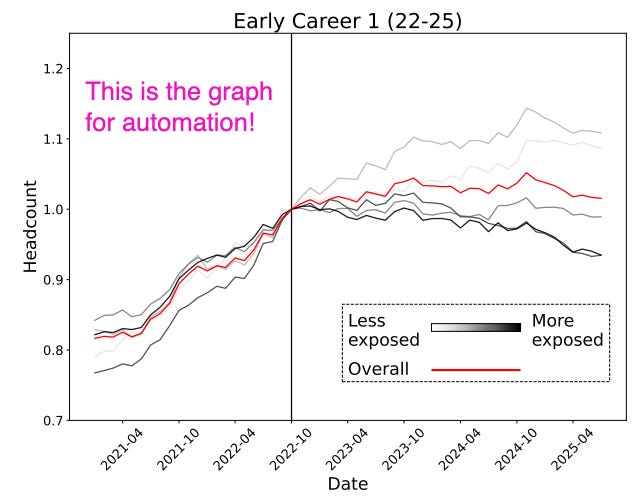

Last week, I got an email from Stanford University alerting me to yet another crack at this question. In a new paper, several Stanford economists studied payroll data from the private company ADP, which covers millions of workers, through mid-2025. They found that young workers aged 22–25 in “highly AI-exposed” jobs, such as software developers and customer service agents, experienced a 13 percent decline in employment since the advent of ChatGPT. Notably, the economists found that older workers and less-exposed jobs, such as home health aides, saw steady or rising employment. “There’s a clear, evident change when you specifically look at young workers who are highly exposed to AI,” Stanford economist Erik Brynjolfsson, who wrote the paper with Bharat Chandar and Ruyu Chen, told the Wall Street Journal.

In five months, the question of “Is AI reducing work for young Americans?” has its fourth answer: from possibly, to definitely, to almost certainly no, to plausibly yes. You might find this back-and-forth annoying. I think it’s fantastic. This is a model for what I want from public commentary on social and economic trends: Smart, quantitatively rich, and good-faith debate of issues of seismic consequence to American society.

To more deeply understand the new Stanford paper, I reached out and scheduled an interview with two co-authors, Erik Brynjolfsson and Bharat Chandar. A condensed and edited version of our interview is below, along with careful analysis of the most important graphs.

Thompson: What’s the most important thing this paper is trying to do, and what’s the most important thing it finds?

Erik Brynjolfsson: There has been a lot of debate out there about AI and jobs for young people. I was hearing companies telling me one thing while studies were telling me another. I honestly didn't know the answer. We went at this with no agenda.

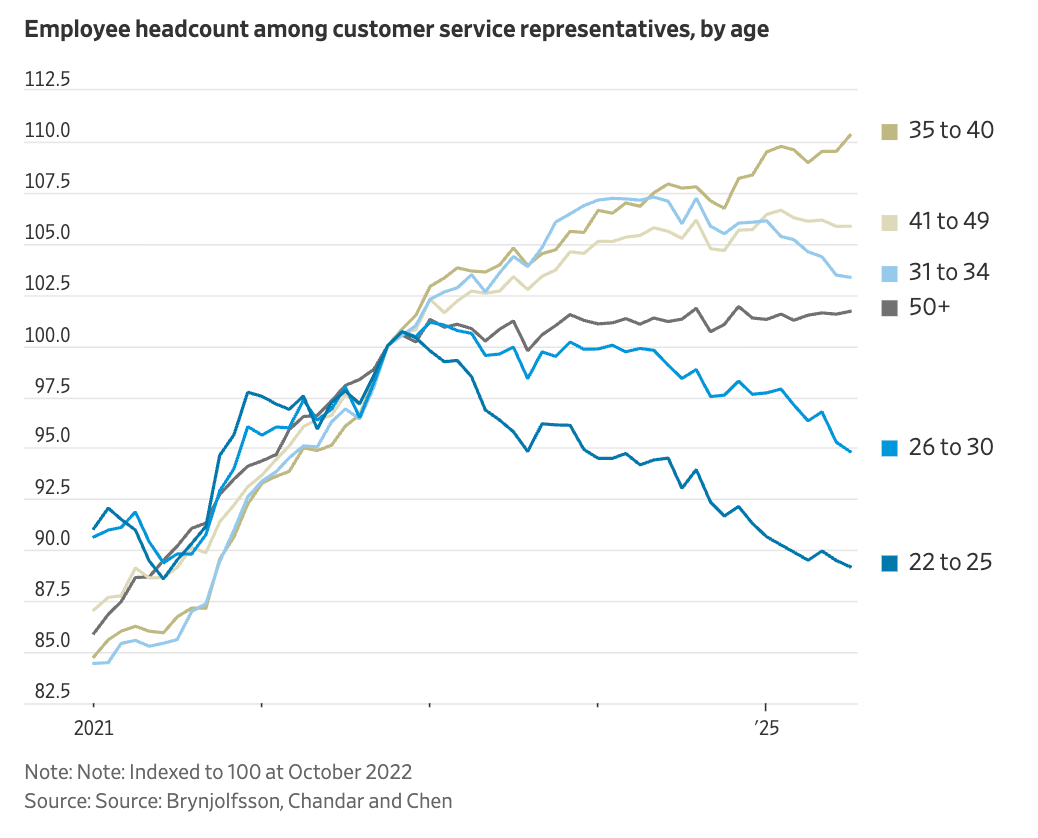

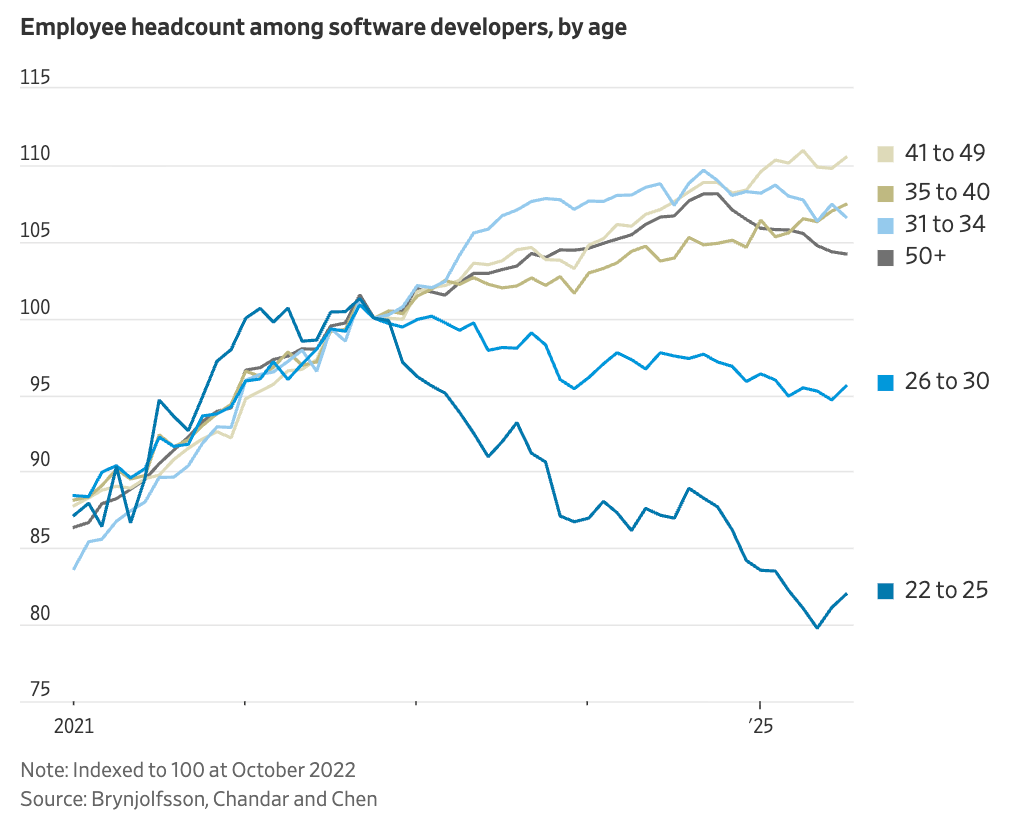

When we were able to slice the data, lo and behold, subcategories of high-exposed jobs like software developers and customer service agents for people aged 22 to 25 saw a very striking decline in employment in the last few years.

Then we asked, what else could this be? We brainstormed alternative hypotheses—COVID and remote work, tech over-hiring and pullback, interest rates—and we put in efforts to address and control for all of those, and the results still showed through clearly.

This is not a causal test, to be clear. We didn’t assign the technology to some firms and not others. But it’s a comprehensive observational analysis that controls for all the obvious alternatives we could think of. We’re happy to add more if people suggest them. Right now, there’s a clear correlation between the most-exposed categories and falling employment for young people.

Thompson: People like to look at graphs, and this will be published as a Q&A on Substack, so why don’t you tell me the key graphs from your paper that make the strongest case for your finding?

Bharat Chandar: I think Figure 1 has drawn a lot of interest, which considers the employment effects among young software engineers/software developers and customer service. We clearly saw hiring decline for young workers specifically, in these occupations.

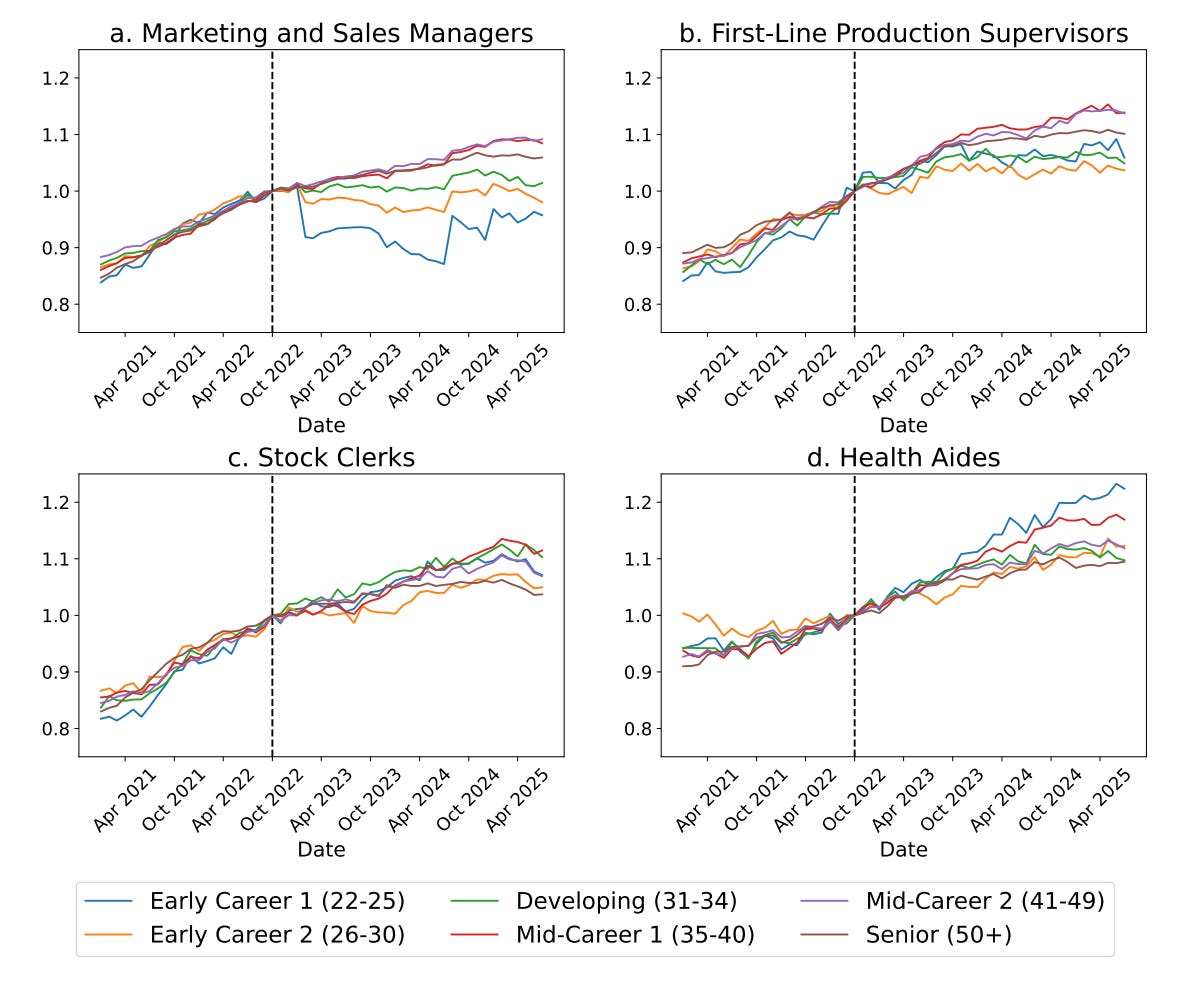

Then I think people have been pretty interested in Figure 2 on the effects for home health aides as well, because here you see the opposite pattern. This is an occupation you wouldn’t think is very exposed to AI, because a lot of the work is in person and physical. And, indeed, you see the opposite pattern. For entry-level worker, there is faster employment growth. So that suggests this isn’t an economy-wide trend. The decline in employment really seems to be more concentrated in jobs that are more AI-exposed.

Thompson: Other research failed to find any effect of AI on employment for young people. Why is your paper different?

Chandar: The main advantage we have is this data from ADP, which tracks millions of workers every single month. That allows us to dig into what’s happening with much more precision.

I actually wrote a paper a couple of months ago using data from the Current Population Survey [CPS], which is a kind of workforce survey for real-time economic outcomes that researchers rely on a lot. My conclusion was similar to pieces by John Burn-Murdoch and others: Across the entire economy, we weren’t seeing major disruptions in the jobs most exposed to AI. But the tricky thing [with CPS] is that when you narrow your analysis to, say, software engineers aged 22 to 25, the sample sizes get very small. You don’t have the precision to say much that’s definitive.

That’s where the ADP data comes in. With millions of observations every month, we can cut the data by age and occupation and get reliable estimates even for small groups like 22–25 year-old software engineers.

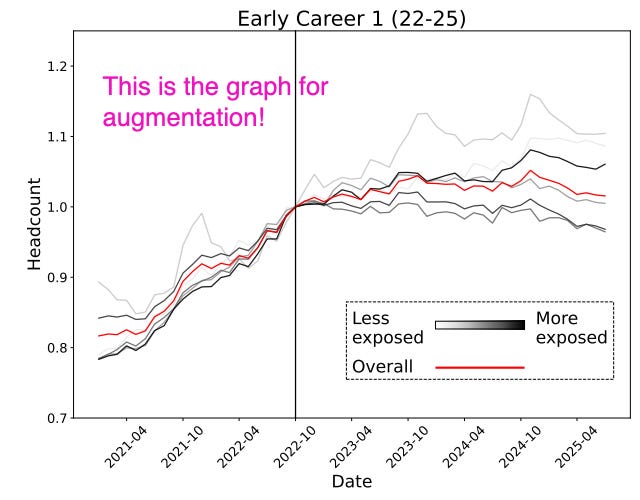

Thompson: One piece of the paper that I love is that you specify the effect of AI in occupations where AI is more likely to automate vs. augment human work. So, "translate this essay into Spanish" or "format this technical document" is a task that can be automated by existing AI. But drafting a marketing strategy for a company is something where a human worker is necessary and might collaborate with AI. How did this distinction between automation versus augmentation play out in the paper?

Chandar: We have different measures of AI exposure. One we use is from Claude, via the Anthropic Economic Index. They analyze conversations that come into Claude and associate them with tasks and occupations. For each occupation, they give a sense of whether usage is more automative or augmentative. Automative means my conversation with AI is completely replacing some work I’d have to do. Augmentative is more like I’m learning by using Claude, asking questions, gaining knowledge, getting validation and feedback. We got an interesting result. For occupations where usage is more automative, we see substantial declines in employment for young people, whereas for augmentative occupations, that’s not true. You can see this in Figures 6 and 7 in the paper. It’s compelling because it shows not all LLM usage results in the same trend. The effect shows up more in the automative uses than the augmentative uses.

Thompson: What kind of jobs are most automative versus augmentative?

Chandar: For automative occupations, a lot of it is software engineering, auditing, and accounting, where there are well-defined workflows and LLMs are good at doing one-off tasks without a lot of feedback. For augmentative cases, you’re looking at more complex or managerial roles. It’s not, “I’m just offloading my task and I’m set.” There’s more back-and-forth, more strategic thinking on top of using the LLM. For those applications, we don’t see the same patterns.

Thompson: Would it be fair to say that within the same company, access to generative AI tools could reduce employment among young workers in one department—say, the legal department, where young hires just read, and look up stuff, and synthesize what they find, and write up reports—but also increase employment in another department, where the technology is more augmentative? So “AI is killing jobs at Company X” is less accurate than “AI is reducing headcount in Department A and increasing it in Department B.” Is that the story?

Chandar: Exactly. We actually have an analysis that confirms almost exactly that. It’s a little technical, but it’s basically what you just said. In one part of the analysis, we control for the firm and find that even within the same company, the more-exposed jobs are declining relative to the less-exposed jobs. In particular, for the most-exposed jobs, there’s a 13% relative decline in employment compared to the least-exposed jobs. That’s compelling because these aren’t trends driven by firm-level, aggregate economic shocks, like interest-rate changes. You’d expect those to apply at the firm level, but even within the firm you see differences between the more-exposed jobs and the less-exposed jobs.

Thompson: What does this suggest about what AI is good at versus what workers are good at?

Brynjolfsson: This is a little speculative, but important. LLMs learn from what’s written down and codified, like books, articles, Reddit, the internet. There’s overlap between what young workers learn in classrooms, like at Stanford, and what LLMs can replicate. Senior workers rely more on tacit knowledge, which is the tips and tricks of the trade that aren’t written down. It appears what younger workers know overlaps more with what LLMs can replace.

Chandar: One thing I’d add is short-time-horizon tasks vs. long-time-horizon tasks. The strategic thinking that goes into longer-horizon tasks may be something LLMs aren’t as good at, which aligns with why entry-level workers are more affected than experienced workers. Another factor is observable outcomes. Tasks where it’s easy to see whether you did a good job may be more substitutable. tThe nature of the training process means AI should, in general, be better at those.

Thompson: Does this paper have any bearing on the question of how colleges should respond to AI or what should students should study?

Brynjolfsson: One obvious category is: learn how to use AI. Paradoxically, I’ve found that senior coders are more familiar with AI than juniors. Universities haven’t updated their curricula. Maybe universities need to explicitly teach not just the principles of coding but also how to use these tools the way people do on the job. Also, there are many things LLMs aren’t very good at. Many jobs have a physical component that may be increasingly important.

So, what did we learn today? I think Noah Smith’s basic approach here is correct. Understanding real-time changes to the economy is hard work, and overconfidence in any direction is unadvisable. But I’m updating in the direction of trusting my initial gut instinct. I think we’re looking at the single most compelling evidence that AI is already affecting the labor force for young people.

This fits into a broader theme that I’m trying to bang on about in my work on AI. All this talk about AI as the technology of the future—will it cure cancer in 2030? or, destroy the world in 2027? or accomplish both, maybe within the same month?—can evade the question of what AI is doing to the economy right now. AI infrastructure spending growth is already keeping annual GDP growth above water. AI is already creating a cheating crisis in high schools and colleges. AI is having interactions with young and anxious people that are already having real-world effects. And, just maybe, AI is already warping the labor market for young people.

Someone once asked me recently if I had any advice on how to predict the future when I wrote about social and technological trends. Sure, I said. My advice is that predicting the future is impossible, so the best thing you can do is try to describe the present accurately. Since most people live in the past, hanging onto stale narratives and outdated models, people who pay attention to what’s happening as it happens will appear to others like they’re predicting the future when all they’re doing is describing the present. When it comes to the AI-employment debate, I expect we’ll see many more turns of this wheel. I cannot promise you that I’ll be able to predict the future of artificial intellignece. But I can promise you that I’ll do my best to describe the wheel as it turns.

One open question here is whether we’re seeing youth employment decrease because AI is effectively replacing entry level workers in these fields, or because executives wrongly *think* AI can or will soon be able to do so?

I’m not closed to the idea that AI is displacing some young workers, but I also see out of touch executives and investors buying into a lot of AI hype that I’m not seeing reflected on the ground. There was a recent study that showed the vast majority of AI initiatives fail: https://fortune.com/2025/08/21/an-mit-report-that-95-of-ai-pilots-fail-spooked-investors-but-the-reason-why-those-pilots-failed-is-what-should-make-the-c-suite-anxious/

I’ve played around with AI in my job, which I’m pretty sure Anthropic would classify as highly exposed to AI (think something similar to accounting). It’s really helpful for a small number of tasks that comprise maybe 10% of my job, but pretty much useless at the rest. If it’s impacting entry level jobs in my field at all, I really think it’s more that those jobs will change a bit than be totally replaced. I suspect that at some point once the AI hype fever breaks, companies will simply reconfigure entry level jobs a bit to incorporate AI and begin hiring again. I could be wrong, but that’s what I’d bet on right now.

It is logical to me that AI would impact some entry level jobs first. The effectiveness of AI bs humans is still to be determined. If AI does replace many “entry level” jobs, where do the humans receive the training necessary to take over the more experienced roles that AI does not seem (at least yet) to be capable of replacing?