The End of Thinking

The rise of AI's "thinking" machines is not the problem. The decline of thinking people is.

This is an expanded and revised version of an essay that originally ran in The Argument, an online magazine where I am a contributing writer.

In the last few months, top AI executives and thinkers have offered an eerily specific and troubling prediction about how long it will be before artificial intelligence takes over the economy. The message is: “YOU HAVE 18 MONTHS.”

By the summer of 2027, they say, AI’s explosion in capabilities will leave carbon-based life forms in the dust. Up to “half of all entry-level white-collar jobs” will be wiped out, and even Nobel Prize-worthy minds will cower in fear once AI’s architects have built a “country of geniuses in a datacenter.”

I do not like this prediction, for several reasons. First, it’s no fun to imagine my imminent worthlessness. Second, it’s hard for me to take seriously economic predictions that resemble a kind of secular Rapture, in which a god-like entity descends upon the earth and makes whole categories of human activity disappear with a wave of His (Its?) hand. Third, and most importantly, the doom-and-gloom 18-month forecast asks us to imagine how software will soon make human capabilities worthless, when the far more significant crisis that I see is precisely the opposite. Young people are already degrading their cognitive capabilities by outsourcing their minds to machines long before software is ready to steal their jobs.

I am much more concerned about the decline of today’s thinking people than I am about the rise of tomorrow’s thinking machines.

The End of Writing, the End of Reading

In March, New York magazine published the sort of cover story that goes instantly viral, not because of its shock value, but, quite the opposite, because it loudly proclaimed what most people were already thinking: Everybody is using AI to cheat their way through school.

By allowing high school and college students to summon into existence any essay on any topic, large language models have created an existential crisis for teachers trying to evaluate their students’ ability to actually write, as opposed to their ability to prompt an LLM to do all their homework. “College is just how well I can use ChatGPT at this point,” one student said. “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” a professor echoed.

The demise of writing matters, because writing is not a second thing that happens after thinking. The act of writing is an act of thinking. This is as true for professionals as it is for students. In “Writing Is Thinking,” an editorial in Nature, the authors argued that “outsourcing the entire writing process to [large language models]” deprives scientists of the important work of understanding what they’ve discovered and why it matters. Students, scientists, and anyone else who lets AI do the writing for them will find their screens full of words and their minds emptied of thought.

As writing skills have declined, reading has declined even more. “Most of our students are functionally illiterate,” a pseudonymous college professor using the name Hilarius Bookbinder wrote in a March Substack essay on the state of college campuses. “This is not a joke.” Nor is it hyperbole. Achievement scores in literacy and numeracy are declining across the West for the first time in decades, leading the Financial Times reporter John Burn-Murdoch to wonder if humans have “passed peak brain power” at the very moment that we are building machines to think for us.

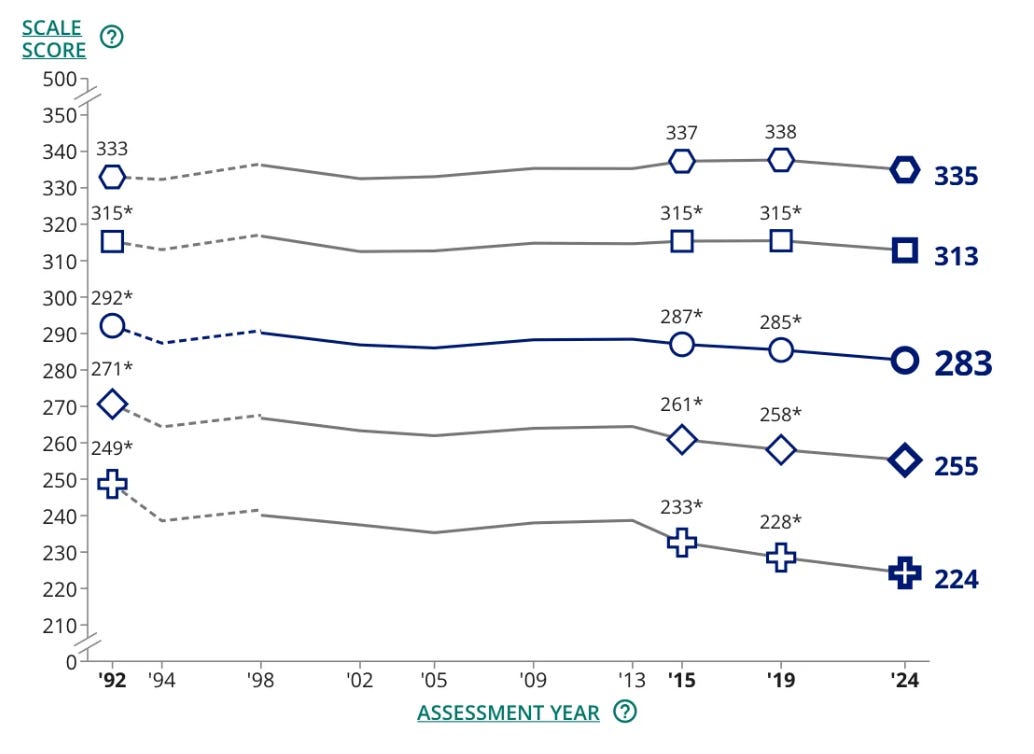

In the U.S., the so-called National Report Card published by the NAEP recently found that average reading scores hit a 32-year low — which is troubling, as the data series only goes back 32 years.

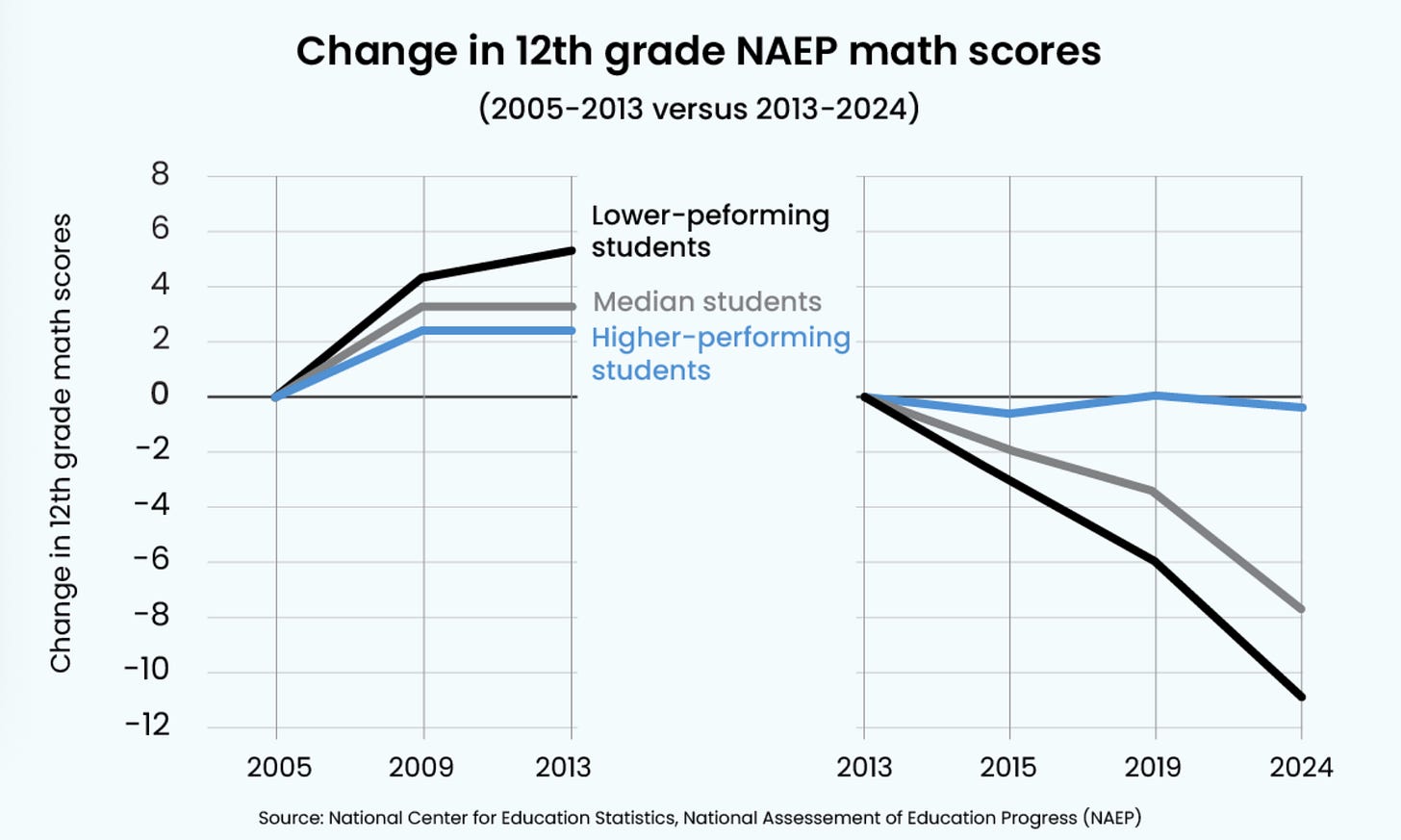

Americans are reading words all the time: email, texts, social media newsfeeds, subtitles on Netflix shows. But these words live in fragments that hardly require any kind of sustained focus; and, indeed, Americans in the digital age don’t seem interested in, or capable of, sitting with anything linguistically weightier than a tweet. The share of Americans overall who say they read books for leisure has declined by nearly 50 percent since the 2000s. In another essay observing that "American students are getting dumber," Matt Yglesias quoted the education writer Chad Aldeman, who has noted that declines in 12th grade scores are concentrated among the worst-performing students.

Even America’s smartest teenagers have essentially stopped reading anything longer than a paragraph. Last year, The Atlantic’s Rose Horowitch reported that students are matriculating into America’s most elite colleges without having ever read a full book. “Daniel Shore, the chair of Georgetown’s English department, told me that his students have trouble staying focused on even a sonnet,” Horowitch wrote. Nat Malkus, an education researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, suggested to me that high schools have chunkified books to prepare students for the reading-comprehension sections of standardized exams. By optimizing the assessment of reading skills, perhaps, the US education system has accidentally contributed to the slow death of book-reading.

The Serum of Literacy

The decline of writing and reading matters because they are the twin pillars of deep thinking, according to Cal Newport, a computer science professor and the author of several bestselling books, including Deep Work. The modern economy prizes the sort of symbolic logic and systems thinking for which deep reading and writing offer the best practice.

AI is “the latest in multiple heavyweight entrances into the prize fight against our ability to actually think,” Newport said. The rise of TV corresponded with the decline in per-capita newspaper subscriptions and a slow demise of reading for pleasure. Then along came the Internet, followed by social media, the smartphone, and streaming TV. As I’ve reported in The Atlantic, the intuition that technology steals our focus has been proven out by several studies that found that students on their phones take fewer notes and retain less information from class. Other research has shown that “task-switching” between social media and homework is correlated with lower GPAs and that students whose cellphones are taken away in experimental settings do better on tests.

“The one-two punch of reading and writing is like the serum we have to take in a superhero comic book to gain the superpower of deep symbolic thinking,” Newport said, “and so I have been ringing this alarm bell that we have to keep taking the serum.”

Newport’s warning echoes an observation made by the scholar Walter Ong in his book Orality and Literacy. According to Ong, literacy is no passing skill. It was a means of restructuring human thought and knowledge to create space for complex ideas. Stories can be memorized by people who cannot read or write. But nothing as advanced as, say, Newton’s Principia could be passed down generation to generation without the ability to write down calculus formulae. Oral dialects commonly have only a few thousand words, while “the grapholect known as standard English [has] at least a million and a half words,” Ong wrote. If reading and writing “rewired” the logic engine of the human brain, the decline of reading and writing are unwiring our cognitive superpower at the very moment that a greater machine appears to be on the horizon.

It would be simple if the solution to AI were to simply ignore it, ban the technology on college campuses, and turn every exam into an old-fashioned blue-book test. But AI is not cognitive fentanyl, a substance to be avoided at all costs. Research in medicine has found that ChatGPT and other large language models are better than most doctors at diagnosing rare illnesses. Rejecting such technology would be worse than stubborn foolishness; it would, in real-life cases, amount to fatal incompetence. There is no clear bright line that tells us when to use an LLM and when to leave that tab closed.

The dilemma is clear in medical schools, which are encouraging students to use LLMs, even as conscientious students will have to take care that their skills advance alongside AI rather than atrophy in the presence of the technology. “I’m worried these tools will erode my ability to make an independent diagnosis,” Benjamin Popokh, a medical student at the University of Texas Southwestern, told the New Yorker. “I went to medical school to become a real, capital-‘D’ doctor,” he said “If all you do is plug symptoms into an A.I., are you still a doctor, or are you just slightly better at prompting A.I. than your patients?” From the article:

On a recent rotation, his professors asked his class to work through a case using A.I. tools such as ChatGPT and OpenEvidence, an increasingly popular medical L.L.M. that provides free access to health-care professionals. Each chatbot correctly diagnosed a blood clot in the lungs. “There was no control group,” Popokh said, meaning that none of the students worked through the case unassisted. For a time, Popokh found himself using A.I. after virtually every patient encounter. “I started to feel dirty presenting my thoughts to attending physicians, knowing they were actually the A.I.’s thoughts,” he told me. One day, as he left the hospital, he had an unsettling realization: he hadn’t thought about a single patient independently that day.

In a viral essay entitled “The dawn of the post-literate society and the end of civilization,” the author James Marriott writes about the decline of thinking in mythic terms that would impress Edward Gibbon. As writing and reading decline in the age of machines, Marriott forecasts that the faculties that allowed us to make sense of the world will disappear, and a pre-literate world order will emerge from the thawed permafrost of history, bringing forth such demons as “the implosion of creativity” and “the death of democracy.” “Without the knowledge and without the critical thinking skills instilled by print,” Marriott writes, “many of the citizens of modern democracies find themselves as helpless and as credulous as medieval peasants, moved by irrational appeals and prone to mob thinking.”

Maybe he’s right. But I think the more likely scenario will be nothing so grand as the end of civilization. We will not become barbarous, violent, or remotely exciting to each other or ourselves. No Gibbon will document the decline and fall of the mind, because there will be no outward event to observe. Leisure time will rise, home life will take up more of our leisure, screen time will take up more of our home life, and AI content will take up more of our screen time. “If you want a picture of the future,” as Orwell almost wrote, “imagine a screen glowing on a human face, forever.” For most people, the tragedy won't even feel like a tragedy. We’ll have lost the wisdom to feel nostalgia for what was lost.

Time Under Tension

… or, you know, maybe not!

Culture is backlash, and there is plenty of time for us to resist the undertow of thinking machines and the quiet apocalypse of lazy consumption. I hear the groundswell of this revolution all the time. The most common question I get from parents anxious about the future of their children is: What should my kid study in an age of AI? I don’t know what field any particular student should major in, I say. But I do feel strongly about what skill they should value. It’s the very same skill that I see in decline. It’s the skill of deep thinking.

In fitness, there is a concept called “time under tension.” Take a simple squat, where you hold a weight and lower your hips from a standing position. With the same weight, a person can do a squat in two seconds or ten seconds. The latter is harder but it also builds more muscle. More time is more tension; more pain is more gain.

Thinking benefits from a similar principle of “time under tension.” It is the ability to sit patiently with a group of barely connected or disconnected ideas that allows a thinker to braid them together into something that is combinatorially new. It’s very difficult to defend this idea by describing other people’s thought processes, so I’ll describe my own. Two weeks ago, the online magazine The Argument recently asked me to write an essay evaluating the claim that AI would take all of our jobs in 18 months. My initial reaction was that the prediction was stupendously aggressive and almost certainly wrong, so perhaps there was nothing to say on the subject other than “nope.” But as I sat with the prompt, several pieces of a puzzle began to slide together: a Financial Times essay I’d read, an Atlantic article I liked, an NAEP study I’d saved in a tab, an interview with Cal Newport I’d recorded, a Walter Ong book I was encouraged to read, a stray thought I’d had in the gym recently while trying out eccentric pull ups for the first time and thinking about how time multiplies both pain and gain in fitness settings. The contours of a framework came into view. I decided that the article I would write wouldn’t be about technology taking jobs from capable humans. It would be about how humans take away their own capabilities in the presence of new machines. We are so fixated on how technology will out-skill us that we miss the many ways that technology can de-skill us.

In movies about impending planetary disasters, we often see the world come together to prepare to meet the threat directly. One might imagine, then, that the potential arrival of all-knowing AI would serve as a galvanizing threat, like a Sputnik moment for our collective capacity to think deeply. Instead, I fear we’re preparing for the alleged arrival of a super-brain by lobotomizing ourselves, slinking away into a state of incuriosity marked by less reading, less writing, and less thinking. It’s as if some astrophysicists believed a comet was on its way to smash into New York City, and we prepped for its arrival by preemptively leveling Manhattan. I’d call that’s madness. Do not let stories on the rise of “thinking machines” distract you from the real cognitive challenge of our time. It is the decline of thinking people.

As a teacher who witnesses this trend in real time, I firmly believe that our schools can be the locus of a solution. The “21st century learning” model that mirrored the marketplace by integrating any and all new technologies failed to account for the business model of the attention economy. Our schools can and should be embodied alternatives to the screen-saturated norm. Cognitive development and attentional capacity need to be design principles in every classroom and every lesson. This CAN be done.

https://open.substack.com/pub/walledgardenedu/p/the-disappearing-art-of-deep-learning?r=f74da&utm_medium=ios

This is hardly the biggest issue, but there are many studies that establish that reading fiction develops empathy. As we read less, this is just another thing we are losing.